Age-related Hyperkyphosis

Original Editors - Louise Burrion

Top Contributors - Louise Burrion, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Mariam Hashem, Yuan Chuang, Evan Thomas, Stijn Van de Vondel, Gayatri Jadav Upadhyay, Oyemi Sillo, Magdalena Hytros, Ajay Upadhyay, Cedric Cludts, WikiSysop, Lauren Lopez, 127.0.0.1, Admin and Borms Killian

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Age-related hyperkyphosis affects 20-40% of older adults and can be described as an exaggerated anterior curvature of the thoracic spine that is associated with aging[1]

- Anterior curvature of the thoracic spine is normal and present due to the shape of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs,

- Kyphosis angle greater than 40° is defined as hyperkyphosis.[1]

General causes of age-related hyperkyphosis that have been reported are poor posture, dehydration of the intervertebral discs and reduced back extensor muscle strength.

Age-related hyperkyphosis may:

- Induce the symptoms such as back soreness, neck pain, numbness of upper extremities or buttock

- Low psychological well-being such as depression and low self-esteem[2]

- Lead to mobility impairments of the rib cage (connected to thoracic spine) which can result in pulmonary difficulties

- Increase biomechanical stress on the spine which can result in an increased risk of development of vertebral compression fractures

- Increase risk of falling and fractures due to poor gait

- Impaired Physical function eg has an impact on the basic functioning and daily living, which affects the quality of life [3][4]

- Mortality - may be a risk factor for premature death. As the kyphotic angle increases, the mortality rate inflates. Some studies have attributed this increase to pulmonary death[5]

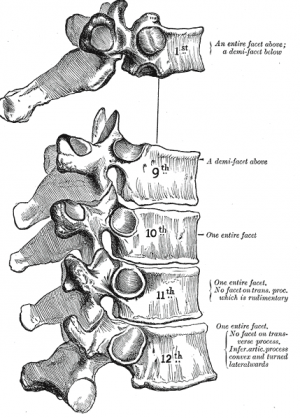

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The spine consists of vertebrae, intervertebral disks and spinal cord and has different regions and curves. The important parts of the thoracic spinal region include:

Thoracic spine is relatively stiff compared to the rest of the spine, because of the rib cage, ligaments and the thin, rigid intervertebral discs.[6][7]

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

- Thoracic kyphosis varies in life between 20-29 degrees.

- Incidence and prevalence of hyperkyphosis vary between 20% to 40% among both men and women. [3]

- After the age of 40 the kyphotic angle begins to increase usually more rapidly in women than men.

- The angle varies between 43 to 52 degrees in women aged 55-60 years to 52 degrees in women between 76-80 years of age.

- Exaggeration of the normal thoracic curvature can be associated with a variety of conditions and psychosocial factors:

- Underlying osteoporosis and vertebral fractures. However, only one-third of those with severe kyphosis measurements have had radiographic confirmation of vertebral fractures.[5]

- Depression, insecurity, despondency and anxiety [8][9]

- Gradual changes in structure and mechanics of connective tissue which in time results in a loss of elasticity and mobility, this causes the inability to counteract gravitation that pulls the body forward [10][3]

- Muscle weakness (often because of a weakening spinal extensor muscle) [10]

- Deficits in the somatosensory, visual and vestibular systems contribute to the loss of upright postural control

- Declining proprioceptive and vibratory input from the joints in the lower extremities results in an impaired perception of erect vertical alignment [3]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Thoracic Hyperkyphosis symptoms (main ones)

- Increased anterior curvature of the thoracic spine. This can come over time and isn’t always detected by the patient, but rather by his friends and family (if a person has a sudden increase of rounded back a doctor appraisal is warranted as can be associated with other health problems).

- Difficulty rising from a chair without their arms

- Poor balance (they have the feeling that they might fall)

- Slower gait velocity

- Wider base of support with stance and gait (to avoid falling)

- Decreased stair climbing speed[3]

- In severe cases of Hyperkyphosis, trouble breathing, because of the loss of vital capacity of the lungs[3]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Osteoporosis

- Vertebrale fracture

- Muscle imbalance caused by neuromuscular disease

- ankylosing spondylitis

- Scheuermann's Kyphosis (see R image)

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

There are different validated diagnostic procedures for measuring hyper-kyphosis:

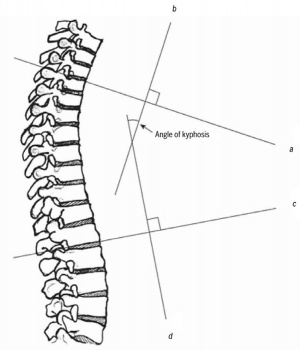

The most validated method for assessing thoracic kyphosis is standing lateral spine radiographs. Used to obtain a Cobbs angle measurement (from lateral spine radiograph) and is the current gold standard for quantifying thoracic kyphosis.[5](Figure at right)

Several non-invasive, skin-surface methods have been used for clinical measurement including the Debrunner’s kyphometer, Flexicurve and Spinal Mouse

- The kyphometer measures the angle of kyphosis. The arms of the device are placed at the top and bottom of the thoracic curve (spinous processes of T2/T3 superiorly, and T1/T12 inferiorly). Using a mathematical formula we can strongly correlate with the radiologic measured thoracic Cobb’s angle.[11]

- The flexicurve ruler is a flexible ruler that is aligned over the C7 spinous process to the L5–S1; the ruler is molded to the curvature of the spine. The kyphosis index is calculated as the width divided by the length of the thoracic curve, multiplied by 100. A kyphosis index value greater than 13 is defined as hyperkyphotic.[12]

- Spinal Mouse ® is a device that, combined with a computer program (PC), assesses the curvatures of the vertebral column without applying harmful radiation.[13]

NB: There is a reasonable correlation (ICC = 0.68) between a radiologic and standing clinical measurement of kyphosis.[14]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Scoliosis Research Society Outcomes Instrument (SRS-22): The SRS -22 scores function, pain, self-image, mental health, and satisfaction with management. There are findings that associate hyperkyphosis with increased pain, lower self-image, and decreased general function and overall activity. The r values for this analysis of kyphosis (0.40–0.66) were significantly greater than those reported for scoliosis magnitude versus SRS questionnaire scores (0.16–0.26). Therefore the SRS outcomes instrument may be even better suited for the evaluation of hyperkyphosis patients. [15]

- Occiput to Wall Distance

- Tragus to wall

- Neck Pain and Disability Scale

- Timed Up and Go TUG

Clinical Examination[edit | edit source]

Hyperkyphotic posture can be examined clinically by therapist's qualitative visual assessment. This could be done by:

- Evaluating the anterior curvature of the spine, keeping in mind that changes in thoracic curvature can be caused by a modified posture in other regions (e.g. lumbar spine)

- Tragus to wall test, Occiput to Wall Distance

- Measurement of the number of 1.5-cm blocks needed to support the head.

There are no studies comparing these measures to the gold-standard radiograph.[16]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Pharmacological treatment - focus on anti-resorptive or bone-building medication because many patients with age-related hyperkyphosis have low bone density or spine fractures.[3]

Two surgical options: vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty[17](Mainly help relieve pain, decrease physical disability, reduce the kyphosis angle).

1. Kyphoplasty - a procedure that is used to reduce the pain in patients that have spinal fractures and to correct spine deformation. [18] [17]

2. Vertebroplasty - surgeon injects an acrylic bone cement directly into the vertebral fracture.[18] [19]This surgery has the same risk as a kyphoplasty, namely leaking fluid and potentially damaging the spinal cord.[18]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

A 2014 systematic review of exercise for age-related hyperkyphotic posture concluded that there are few high-quality studies suggesting a modest benefit (1.67°-3.74° decrease of hyperkyphosis) for exercise compared to control.[4]

Exercises should (initially) be supervised by a physical therapist or certified instructor in order to be effective and safe.

Exercise modalities and dosage should be adapted to capacities and needs of the individual patient.

The main goals of physical therapy management should be: [3]

- Increased back extensor strength

- Increased spinal extension mobility

- Improved postural awareness

- Prevention of vertebral compression fractures

- Maintain or restore the physical function and prevent further deterioration

PT Management strategies include[20]:

- Postural correction training through stretching and strengthening exercises to help reduce the hyperkyphotic curvature and prevent the condition from advancing.

- Breathing exercises help improve tolerance for physical activity by increasing lung capacity. eg. Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercises

- Pain management using modalities such as heat, ice, and/or electrical stimulation such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

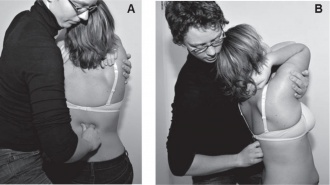

- Myofascial/soft tissue manual therapy (using hands-on techniques) and shoulder mobilization to help improve spinal flexibility.

- Specialized braces or therapeutic taping to help reduce the angle of the curve.

- Education to improve posture and activities of daily living and ease physical functioning.

- Balance exercises and gait training to increase general fitness and reduce risk of falls.

Exercise modalities include:

(All modalities below has been studied using RCTs: level of evidence= 1B)

- Hatha Yoga modified for individuals with hyperkyphosis[21]:Postures should focus on breathing techniques, stretching tight muscle groups and strengthening weak/inhibited muscle groups (e.g. rhomboids)

- Manual mobilisations[22] [23]: Mobilisations should be done according to Maitland Joint Mobilization Grading Scale

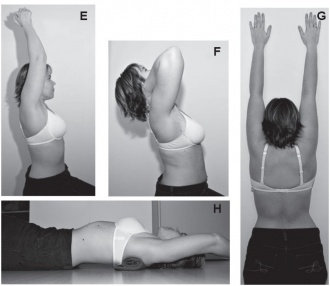

- Active mobilisations/stretches of pectoral region, shoulders and Latissimus Dorsi muscle[24][22][23]

- Muscle strengthening[25] [22][26] [27]:Thoracic extension (paravertebral muscles), abdominal muscles, scapular adductors, shoulder flexion, adduction, abduction [25] and standing elbow flexion/extension

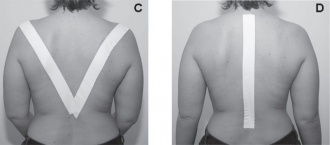

- Postural awareness training (In standing and sitting posture): visual (images or mirror), auditive (with therapist giving cues) and/or tactile feedback (therapist, taping). [22] [23][25]

Postural awareness training steps:

- Explain to the patient what the problematic posture is

- Demonstrating correct posture, explaining every motion that should be made:

- Belly button in & down (soft contraction)

- Knees slightly bent

- Shoulders back (=scapular retraction): it can help to do external rotation in the shoulder to accompany this motion

- Chest up

- Chin slightly tucked in

- Have the patient try this him/herself, the first time still going over every cue. Once the patient has practiced the posture a sufficient number of times to immediately be able to resume good posture on command, taping and random reminders (timer) can be used to ensure the posture is kept during the day.

Concluding Remarks[edit | edit source]

Kyphosis is common in older individuals, increases the risk for fracture and mortality, and is associated with impaired physical performance, health, and quality of life.

Screening for hyperkyphosis could be easily implemented in the clinical setting and the evidence to date suggests that relatively simple, available, and inexpensive conservative interventions have a beneficial effect to reduce hyperkyphosis, improve the quality of life and reduce risk for future fractures for men and women, including:

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jang et al., H. (2015). Effect of thorax correction exercises on flexed posture and chest function in older women wih age-related hyperkyphosis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. , 27, 1161-1164.

- ↑ Jang, H.-J., Hughes, L. C., Oh, D.-W., & Kim, S.-Y. (2019). Effects of Corrective Exercise for Thoracic Hyperkyphosis on Posture, Balance, and Well-Being in Older Women: A Double-Blind, Group-Matched Design. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy, 42(3), E17–E27. https://doi.org/10.1519/JPT.0000000000000146

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Katzman et al., W. B. (2010). Age-related hyperkyphosis: its causes, management, and consequences. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther , 40, 352-360. (LoE: 5)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bansal et al., S. (2014). Exercise for Improving Age-Related Hyperkyphotic Posture: A systematic Review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil , 95 (1), 129-140. (LoE: 1a)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Roghani T, Zavieh MK, Manshadi FD, King N, Katzman W. Age-related hyperkyphosis: update of its potential causes and clinical impacts—narrative review. Aging clinical and experimental research. 2017 Aug;29(4):567-77.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5316378/(Last accessed 18.4.2020)

- ↑ http://www.spineuniverse.com/conditions/kyphosis/anatomy-kyphosis

- ↑ Mulligan et al., B. (2015). The Mulligan Concept of Manual Therapy: Textbook of Techniques. Chatswood, NSW, Australia: Elsevier.

- ↑ Fon et al., G. (1980). Thoracic kyphosis: range in normal subjects. AJR Am J Roentgenol , 134 (5), 979-83.

- ↑ Lewis et al., J. (2010). Clinical measurement of the thoracic kyphosis. A study of the intra-rater reliability in subjects with and without shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders , 1 (11), 39.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Hinman et al., M. (2004). Comparison of thoracic kyphosis and postural stiffness in younger and older women. Spine J , 4 (4), 413-7.

- ↑ Korovessis et al. (2001). Prediction of thoracic kyphosis using the Debrunner kyphometer. J Spinal Disord , 67-72.

- ↑ Teixeira et al. (2007). Reliability and validity of thoracic kyphosis measurements using the flexicurve method. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy , 199-204.

- ↑ Bowtech Spinal Mouse Available from:https://spinalmouse.ro/en (last accessed 18.4.2020)

- ↑ Kado et al. (2006). Comparing a supine radiologic versus standing clinical measurement of kyphosis in older women: the Fracture Intervention Trial. Spine , 463-467.

- ↑ Petcharaporn et al. (2007). The Relationship Between Thoracic Hyperkyphosis and the Scoliosis Research Society Outcomes Instrument. Spine , 226-231.

- ↑ Kado DM. (2009). The rehabilitation of hyperkyphotic posture in the elderly. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med , 583-93

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Goh et al. (2000). A comparison of three methods for measuring thoracic kyphosis: implications for clinical studies. Rheumatology , 310-315.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Pradhan et al., B. (2006). Kyphoplasty reduction of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: correction of local kyphosis versus overall sagittal alignment. Spine , 15 (31(4)), 435-41.

- ↑ Wardlaw et al., D. (2009). Efficacy and safety of balloon kyphoplasty compared with non-surgical care for vertebral compression fracture (FREE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet , 373 (9668), 1016-24.

- ↑ http://www.moveforwardpt.com/SymptomsConditionsDetail.aspx?cid=a26d7f6b-85dd-4461-9685-be7a8e5d5725

- ↑ Greendale et al., G. (2009). Yoga decreases kyphosis in senior women and men with adult-onset hyperkyphosis: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc , 57, 1569-79.(LoE: 1b)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Bautmans et al., I. (2010). Rehabilitation using manual mobilization for thoracic kyphosis in elderly postmenopausal patients with osteoporosis. J Rehabil Med. , 42, 129-135. (LoE: 1b)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Bennell et al., K. (2010). Effects of an exercise and manual therapy program on physical impairments, function and quality-of-life in people with osteoporotic vertebral fracture: a randomised, single-blind controlled pilot trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord , 11-36. (LoE: 1b)

- ↑ https://www.t-nation.com/training/heal-that-hunchback

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Abreu et al., D. (2012). The effect of physical exercise on thoracic hyperkyphosis in elderly postmenopausal patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Int. , 23, 120. (LoE: 1b)

- ↑ Benedetti et al., M. (2008). Effects of an adapted physical activity program in a group of elderly subjects wtih flexed posture: clinical and strumental assessment. J Neuroeng Rehabil , 5, 32. (LoE: 2b)

- ↑ Itoi et al., E. (1994). Effects of back-strengthening exercise on posture in healthy women 49 to 65 years of age. Mayo Clin Proc , 69, 1054-9. (LoE: 1b)

- ↑ Katzman WB, Wanek L, Shepherd JA, Sellmeyer DE. Age-related hyperkyphosis: its causes, consequences, and management. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2010 Jun;40(6):352-60. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2907357/ (last accessed 18.4.2020)