Cardiovascular Considerations in the Older Patient

Original Editor - Wendy Walker

Top Contributors - Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Wendy Walker, Andeela Hafeez, Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, WikiSysop, Fasuba Ayobami, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Vidya Acharya and Lauren Lopez

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Age-related Changes in the Cardiovascular System normally occur, with aging being an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. However, many other changes that are common with ageing are due to or worsened by modifiable factors.

The effects of ageing are widely diverse and can be identified at the molecular, cellular, tissue, organ, and system levels as contributing to the altered function of the cardiovascular system[1][2]. These changes are outlined below

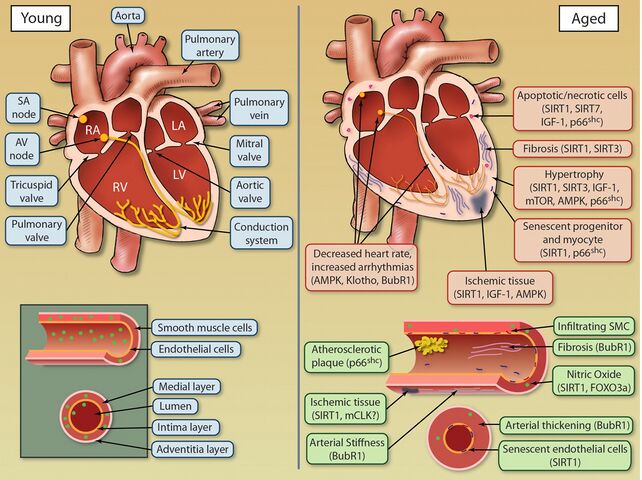

Age-Related Heart Structural Changes[edit | edit source]

Structural changes with ageing involve the

- Myocardium

- Cardiac conduction system

- Endocardium.

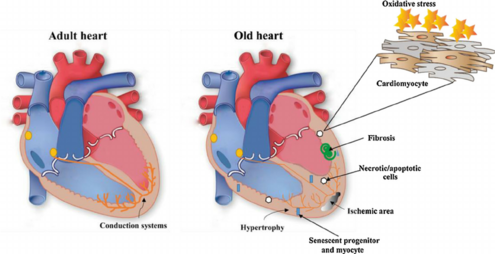

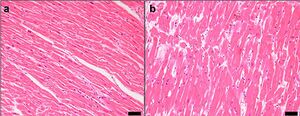

There is a progressive degeneration of the cardiac structures with a loss of elasticity, fibrotic changes in the valves of the heart, and infiltration with amyloid. The age-associated structural characteristics that have the greatest impact involve the contractility of the heart's left ventricular wall. The pumping capacity of the heart is reduced with age due to a variety of changes affecting the structure and function of the heart muscle.

Evidence suggests that between the second and the seventh decade an increase in the left ventricular posterior wall thickness of approximately 25% occurs. This increase in heart mass, for the most part, is due to an increase in the average myocyte size, whereas the number of myocardial cells declines.[3] The decline in left ventricular compliance provides an increased workload on the atria, resulting in hypertrophy of the atria.[4]

Note these changes in function:

- Cardiac output at rest is unaffected by age. Maximum cardiac output and aerobic capacity are reduced with age.

- Stroke volume is changed little by aging; at rest in healthy individuals, there may even be a slight increase.

- Blood pressure is a measure of cardiovascular efficiency. In general, most older people have a moderate increase in blood pressure[1].

Cardiac conduction system[edit | edit source]

Cardiac conduction is affected by the decrease in the number of pacemaker cells in the sinoatrial node with age. Beginning by age 60 there is a pronounced decrease, in the number of pacemaker cells in the sinoatrial node, and by age 75 less than 10% of the cell number found in the young adult remains. With advancing age, there is an increase in elastic and collagenous tissue in all parts of the conduction system. Fat accumulates around the sinoatrial node, sometimes producing a partial or complete separation of the node from the atrial musculature. The conduction time from the bundle of His to the ventricle is not altered.

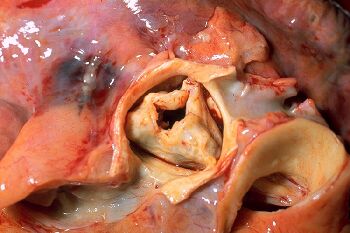

Valves[edit | edit source]

An age-related increase in valvular circumference has been reported in all four cardiac valves (aortic semilunar valve, semilunar valve, bicuspid valve, tricuspid valve), with the greatest changes occurring in the aortic valve (the valve between the left ventricle and the aorta).

Calcific deposits frequently are present [5] on one or more aortic valve cusps. These changes do not usually cause significant dysfunction, although in some older adults, severe aortic valvular stenosis and mitral valvular insufficiency are related to degenerative changes with age. Clinical heart murmurs are detected more frequently. See Auscultation

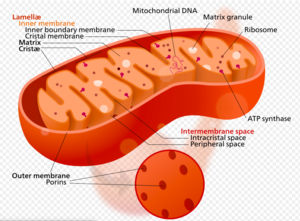

Myocardial Subcellular Changes[edit | edit source]

The nucleus, containing DNA, becomes larger and may show invagination of its membrane.The mitochondria show alterations in size, shape, cristal pattern, and matrix density, which reduce their functional surface.The cytoplasm is marked by fatty infiltration or degeneration, vacuole formation, and a progressive accumulation of pigments such as lipofuscin. The combined age-related changes in the subcellular compartments of the cells result in decreased cellular activities such as altered homeostasis, protein synthesis, and degradation rates.[6]

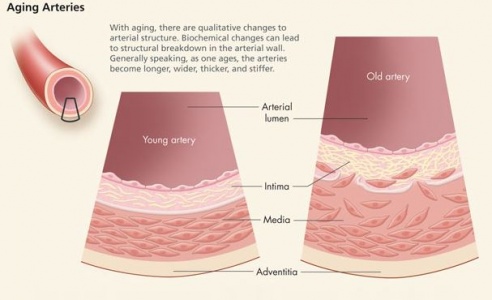

Age-Related Changes in the Blood Vessels[edit | edit source]

The decrease of elasticity of the arterial vessels with aging may result in chronic or residual increases in vessel diameter and vessel wall rigidity, which impair the function of the vessel. Factors that contribute to the increased wall thickening and stiffening in aging include increased collagen, reduced elastin, and calcification.

- The aorta becomes thicker, stiffer, and less flexible. This is probably related to changes in the connective tissue of the blood vessel wall. This makes the blood pressure higher and makes the heart work harder, which may lead to hypertrophy of the myocardium.

- Ateries thicken and stiffen. In general, most older people have a moderate increase in blood pressure[7]. Receptors called baroreceptors monitor the blood pressure and make changes to help maintain a fairly constant blood pressure when a person changes positions or is doing other activities. The baroreceptors become less sensitive with ageing, possibly explaining why many older people have orthostatic hypotension.

- The thickening of the basement membrane of the capillary walls means that the delivery of oxygen and nutrients is slower than in younger people, although there is some evidence to suggest that this effect is modifiable with high levels of exercise[8].

- The walls of veins may become thicker with age because of an increase in connective tissue and calcium deposits. and the valves become stiff and incompetent. Varicose veins may develop.[9]

Heart Rate[edit | edit source]

As we age, one of the most notable changes in the cardiac system is the decline in maximal heart rate, see link.

The reduction in maximal heart rate is thought to be due to changes in the autonomic nervous system[10][11], along with age-related decrease in the number of cells in the sinoatrial node.

Consequences of Reduction in Maximum Heart Rate

- Smaller aerobic workload possible - ie. reduction in the extent of cardiac exertion that can be tolerated for a period of time

- Slower aerobic performance - eg. 90-year-olds completing the New York City marathon typically do so in 7-8 hours

Reduction in Contractitility of Vascular Walls: This contributes to the slowing of heart rate, lower VO2 max and results in a reduction in the aerobic workload possible.

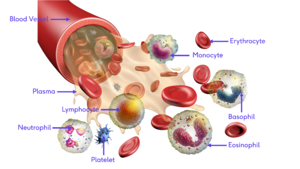

Blood[edit | edit source]

Blood The blood itself changes slightly with age.

- Normal ageing causes a reduction in total body water. Consequently there is less fluid in the bloodstream, so blood volume decreases.

- Red blood cells are produced more slowly in response to stress or illness is reduced. This creates a slower response to blood loss and anemia.

- Most of the white blood cells stay at the same levels, although neutrophils decrease in their number and ability to fight off bacteria. This reduces the ability to resist infection.[1]

Age-Related Cardiovascular Changes and Exercise[edit | edit source]

Moderate exercise is one of the best things older persons can do to keep their heart, and the rest of their body, healthy. Lifestyle factors such as physical activity and exercise have a significant impact not only on preventing cardiovascular diseases later in life, but also attenuating age-related cardiovascular function decline in the absence of disease. Note:

- Long lasting exercise training of several years and/or decades is associated with improved cardiovascular function in later life

- Exercise interventions performed by previously sedentary individuals provide a significant health benefits, and can reverse, to some extent, age-related decline in cardiovascular function further leading to improved quality of life and functional independence[12]

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

See Cardiovascular Exercises For elderly, Age and Exercise, Physical Activity in Older Adults, Exercise and Protein Supplements, Heart Rate

Viewing[edit | edit source]

This great 11 minute video summarises the changes in the cardiovascular system in the elderly population.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Medline plus Aging changes in the heart and blood vessels Available:https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004006.htm(accessed 4.4.2022)

- ↑ Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, Minson CT, Nigg CR, Salem GJ, Skinner JS. Exercise and Physical Activity for Older Adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & exercise: Official Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009. 41 (7): 1510-1530. Available from https://www.bewegenismedicijn.nl/files/downloads/acsm_position_stand_exercise_and_physical_activity_for_older_adults.pdf (accessed 5.4.2022)

- ↑ geriatric physical therapy Dale L. Avers, PT, MSEd Vice President of Academic Affairs Rocky Mountain University of Health Professions Los Angeles, California

- ↑ geriatric physical therapy Dale L. Avers, PT, MSEd Vice President of Academic Affairs Rocky Mountain University of Health Professions Los Angeles, California

- ↑ Section of Cardiovascular Pathology, Department of Pathology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/clc.4960110802/pdf

- ↑ geriatric physical therapy Dale L. Avers, PT, MSEd Vice President of Academic Affairs Rocky Mountain University of Health Professions Los Angeles, California

- ↑ Clinical Hypertension and Vascular Diseases: Hypertension in the Elderly Edited by: L. M. Prisant © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ

- ↑ Schroeder TE, Hawkins SA, Hyslop D, et al: Longitudinal change in coronary heart disease risk factors in older runners. Age Ageing 36(1):57–62, 2007

- ↑ https://healthplexus.net/files/images/2009/CGSreport/1208Fruetelfig1.jpg (Accessed September 11, 2017)

- ↑ Heckman GA, McKelvie RS: Cardiovascular aging and exercise in healthy older adults. Clin J Sport Med 18:479-485, 2008

- ↑ Brown SP, Miller WC, Eason JM: Exercise physiology: basis of human movement and disease, Baltimore, MD, 2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

- ↑ Jakovljevic DG. Physical activity and cardiovascular aging: Physiological and molecular insights. Experimental gerontology. 2018 Aug 1;109:67-74.Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0531556517301006(accessed 5.4.2022)

- ↑ Cynthia Escobar. CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM IN ELDERLY POPULATION. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3d5RmQ6uRA [last accessed 6.4.2022]