Pulmonary Fibrosis

Original Editor - Lydia Xenou

Top Contributors - Alfred Chan, Jenna Aiuto, Lydia Xenou, Kim Jackson, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Evan Thomas, Michelle Lee and WikiSysop

Definition[edit | edit source]

Pulmonary or interstitial fibrosis is a descriptive term given when there is an excess of fibrotic tissue in the lung. It can occur in a wide range of clinical settings and can be precipitated by a multitude of causes.[1]

This a serious condition that can result in respiratory failure and death. To avoid high morbidity and mortality, early diagnosis, and treatment are necessary[2].

The term should not be confused with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which is a progressive fibrotic lung disease.[1]

Pathology[edit | edit source]

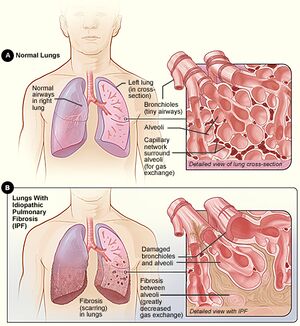

Fibrosis in the lung is a process that occurs in the interstitium. Pulmonary fibrosis can be localised, segmental, lobar, or affect the entirety of the lung(s). [1]

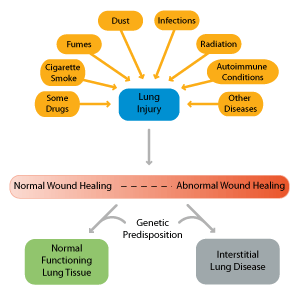

There are over 200 known causes of non-IPF. The etiology for the most common causes are often categorized, as shown below:

- Significant acute insult to the lungs eg adult respiratory distress syndrome , from a significant pulmonary infection, diffuse alveolar damage from any source

- Inhaled substances eg coal/silica: progressive massive fibrosis, asbestos: asbestos-related pulmonary fibrosis

- Radiation: radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis

- Congenital conditions eg cystic fibrosis, Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome

- Autoimmune conditions

- Connective tissue disorders

- Granulomatous conditions ( eg sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis)

- Ageing - some studies report thin-section CT findings associated with interstitial lung disease to some degree are frequently seen in "asymptomatic" elderly individuals [1]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Patients with suspected non-IPF should undergo laboratory and radiographic testing. In some cases, it may be necessary to perform a biopsy[2]. Testing is tailored to the patient’s history and physical findings. The diagnois of this disease requires the use of a multidisciplinary team which will include pulmonologists, radiologists, and pathologists. [3]

- If there is a clear association with another illness or the lung fibrosis is the result of a side effect from a medication or an exposure to an agent known to cause PF, then the cause of the disease is no longer considered idiopathic.

- PF clearly associated with another disease, such as scleroderma or rheumatoid arthritis, would be referred to as pulmonary fibrosis secondary to scleroderma or secondary to rheumatoid arthritis.[4]

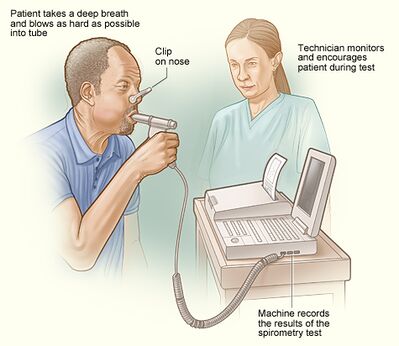

Pulmonary function testing (PFT) should be obtained in all patients. PFTs are essential in the evaluation and diagnosis of non-IPF and are often used to assess disease severity and monitor disease progression. A complete PFT should include spirometry, body plethysmography, DLCO along with resting and ambulatory pulse oximetry. Patients with non-IPF typically have a restrictive pattern and a decrease in DLCO. The frequency of testing varies; however, it’s most often completed annually[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The epidemiology of non-IPF varies based on the underlying cause of the disease.

- Pulmonary fibrosis of all types is slightly more common in men than women and often occurs in the fifth or sixth decades of life in both the United States and worldwide. The overall incidence of ILD of all types is 31.5 per 100,000 in men and 26.1 per 100,000 in women. The estimated prevalence ranges from 25 to 74 per 100,000 population.[2]

- IPF tends to be commoner in males, with most cases presenting in those over 60 years of age. Though, it might be also seen in middle-aged adults, particularly in those with familial risk for pulmonary fibrosis[5]

Signs and Symtoms[edit | edit source]

Individuals with long term Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) may not show any symptoms but as scarring continues to progress within the lungs, patient might have:

- Diffculity in breathing (Dyspnea)

- An unproductive cough that is persistent

- Shortness of breath (especially when engaging in activities such as walking)

- Greater levels of fatigue

- low-grade fevers

- Muscular pain (myalgias)

- Joint pain (arthralgias)

- Unexplained weight loss

- Clubbing in fingers and toes

Future Research for PF

In patients presenting with PF, the development and progression of the healing response has slipped out of control, disrupting many delicate cycles occuring in the body's respiratory system. Although there are a number of compensatory and redundant processes which occur in the body to contribute to proficient healing and remodeling, there is a lack of therapeutic intervention and new therapies to treat the diease. Further studies are required to understand the role of chemical mediators in patients presenting with PF, so that theraputic interventions can be progressed in years to come to limit the burden of this prevalent health condition. [6]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Although there are numerous known causes of non-IPF, the pathogenesis is similar between most diseases. The process involves phases of injury, inflammation, and repair.

There is recurrent and direct epithelial/endothelial injury to the distal air spaces due to various causes (e.g., drug toxicity, environmental exposure, autoimmune reactions).

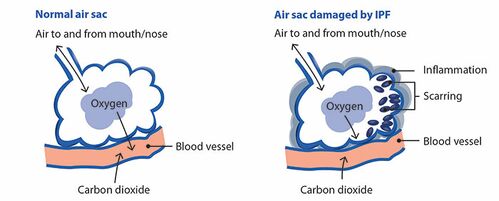

- Destruction of the alveolar-capillary basement membrane leads to platelet activation and fibrin-rich clot formation.

- Macrophages release proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, resulting in chemotaxis of neutrophils.

- The release of cytokines, reactive oxygen species, proteases, and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) amplifies the inflammatory process. TGF-β released by macrophages and damaged tissue promotes fibroblast proliferation resulting in myofibroblast formation and secretion of fibrous proteins and ground substance, which form the extracellular matrix (ECM).

- Chronic inflammation from repetitive injury over time leads to continued thickening and fibrosis of the lung parenchyma. This process ultimately results in irreversible fibrosis and impaired gas exchange

The alveoli in the lungs are responsible for gas exchange (they move oxygen to the capillaries and pick up carbon dioxide from the blood to the breathed out). Due to the scarring of the lung tissue in PF, this process can not be carried out properly. This leads to the many symptoms of PF including shortness of breath and a dry cough. [7]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Generally, the management of chronic disease primarily involves supportive measures including:

- Smoking cessation, influenza vaccination, pneumococcal vaccination, pulmonary rehabilitation, and instructing patients to avoid injurious agents (e.g., avoiding amiodarone in drug-induced fibrosis).

- Supplemental oxygen therapy may be necessary for patients with hypoxemia with a partial pressure of oxygen less than 55 mmHg or oxygen saturation of less than or equal to 88%.

- Further treatments vary based on the specific diagnosis. Corticosteroids may be used in certain conditions (e.g., sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis).

- A lung transplant may be considered as an option in severe or progressive disease. Patients should be evaluated early to be placed on the transplant waiting list[2]

Treatment courses for pulmonary fibrosis are highly variable and difficult to predict. Each therapy strategy is individualized according to the patient's history and symptoms.

Acute exacerbations often occur and present as acute respiratory failure. In addition to supplemental oxygen, management typically involves intravenous corticosteroids (first-line).[2]

- Pulmonary rehabilitation programs: involve aerobic conditioning, strength and flexibility training, educational lectures, nutritional interventions, and psychosocial support. Pulmonary rehabilitation has recently been studied in patients with ILD. Two controlled trials of pulmonary rehabilitation in IPF have demonstrated an improvement in walk distance and symptoms or quality of life. Other uncontrolled studies have found similar findings. The beneficial effects of pulmonary rehabilitation may be more pronounced in patients with worse baseline functional status. Pulmonary rehabilitation may not be reasonable in a minority.[8]

- Lung transplantation: for IPF patients confer a survival benefit over medical therapy. Due to the use of the Lung Allocation Score(LAS) IPF has now replaces COPD as the most common indication for lung transplantation in the United States.[9]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Due to the unknown cause of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, prevention of the respiratory disease is difficult. Higher prevalence of the disease is attributed with certain family genetics and cigarette smokers. As such, a physiotherapist can advise patients to avoid or stop smoking in order to decrease the chance of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Complications[edit | edit source]

There are numerous complications that can occur depending on the specific etiology, particularly in those with systemic illnesses. The following is a list of a few well-known complications in those with nonidiopathic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis:

- Acute and/or chronic respiratory failure

- Irreversible pulmonary fibrosis

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension in those with systemic sclerosis

- Cor pulmonale

- Thromboembolic disease

- Malignancy

- Spontaneous pneumothorax[2]

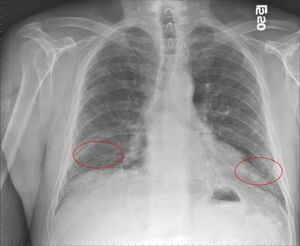

Image: PF lungs

Physiotherapy in Pulmonary Fibrosis Management[edit | edit source]

The goals of physiotherapy management in Pulmonary fibrosis include the following:

- Maximize the patient's quality of life, general health and wellbeing.

- Educate the patient about PF, self management, ceasing of smoking, prevention of infections.

- Optimize alveolar ventilation.

- Optimize lung volumes and capacities.

- Reduce the work of breathing.

- Maximize aerobic capacity and efficiency of oxygen transport.

- Optimize physical endurance and exercise capacity.

- Optimize general muscle strength and thereby peripheral oxygen extraction.

Patient monitoring: includes

- Dyspnea, respiratory distress, breathing pattern (depth and frequency), oxygen saturation, heart rateand blood pressure.

- Patients with cardiac dysfunction or low arterial oxygen tensions require ECG monitoring, particularly during exercise.

- Breathlessness is accessed using a modified version of the Borg scale of perceived exertion.

- 6 minute walk test: Desaturation below the threshold of 88% during the 6MWT has been associated with an increased mortality[6].

Primary interventions (for maximizing cardiopulmonary function and oxygen transport) include combination of:

- Education: includes information in preventative health practices, such as removing from the causative environment, flu shots, smoking reduction and cessation, weight control, hydration, relaxation, energy conservation.

- Aerobic exercise: note patients with PF are prone to arterial desaturation. Patients who desaturate during sleep, require supplemental oxygen during exercise. [10]

- Strengthening exercises: possibly in combination with protein supplements

- Chest wall mobility exercises

- Body positioning

- Breathing techniques

- Pacing and energy and energy conservation.

- Ergonomic assessment of home and work environments may be indicated to maximize function in these settings.

Multidisciplinary Team in Pulmonary Fibrosis Management [edit | edit source]

Nonidiopathic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis requires an interprofessional team approach to optimize care and outcomes for the patient. This requires adequate communication between consultants, primary care physicians, nursing staff, and rehabilitation specialists.

Advanced directives and goals of care should also be established early in the course of the disease. Patients should be extensively educated on their disease and the importance of modifying factors (i.e., smoking cessation, avoidance of harmful substances, and treatment of systemic illnesses).[2]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Radiopedia Pulmonary Fibrosis Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/pulmonary-fibrosis(accessed 12.5.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Agarwal AK, Huda N. Interstitial Pulmonary Fibrosis. Sarcoidosis.;12:13. 2021 Available from:https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/28028/ (accessed 12.5.2021)

- ↑ Prasad R, Gupta N, Singh A, Gupta P. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Current Issues. Intractable Rare Dis Res 2015;4:65-69.

- ↑ Pulmonary fibrosis foundation. About pulmonary fibrosis. [1] (accessed 25 March 2014).

- ↑ Radiopedia Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/idiopathic-pulmonary-fibrosis?lang=gb(accessed 12.5.2021)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wilson M, Wynn T. Pulmonary Fibrosis: pathogenesis, etiology and regulation. Mucosal Immunology 2009;2: 103-121.

- ↑ British Lung Foundation. Disease Fact sheet: What is IPF?.http://www.blf.org.uk/Page/What-is-IPF (accessed 18 May 2015).

- ↑ American Thoracic Society documents. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183:788-824.

- ↑ Medscape. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. [2] (accessed 25 March 2014).

- ↑ Frowfelter D, Dean E. Principles and practice of Cardiopulmonary physical therapy. 3rd ed. St.Louis: Mosby-Year book, 1996.