Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA)

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The clinical definitions of Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA) and ischemic stroke are based on focal neurologic signs or symptoms referable to known cerebral arterial distributions without direct measurement of blood flow or cerebral infarction. It is important to note that TIA and stroke represent different ends of an ischemic continuum from the physiologic perspective, but clinical management is similar[1].

The definition of a TIA has moved from time-based to tissue-based. A TIA

- Typically lasts less than an hour, more often minutes

- It can be considered as a serious warning for an impending ischemic stroke - the risk is highest in the first 48 hours following a TIA. Differentiating TIA from other mimicking conditions is important.

- Usually associated with a focal neurologic deficit and/or speech disturbance in a vascular territory due to underlying cerebrovascular disease

- Always sudden in onset.

Evaluation of TIA should be done urgently with imaging and laboratory studies to decrease the risk of subsequent strokes. The subsequent risk of TIA or ischemic stroke can be stratified with a simple clinical measure. Immediate multimodality therapeutic interventions should be initiated.[2]

The concept of TIA emerged in the 1950s, with the observation by C Miller Fisher, and others, that ischemic stroke often followed transient neurological symptoms in the same arterial territory[3].

Differentiating Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attacks[edit | edit source]

In the 1960s, transient ischemic attacks were considered to be sudden, focal neurological deficits of vascular origin lasting less than 24 h (an arbitrarily assigned endpoint). A stroke was considered to have occurred if a neurological deficit remained for more than seven days. Those neurological events that lasted between 24 h and the seven-day stroke threshold were classified as a reversible ischemic neurological deficit – a term now rendered obsolete. Its removal definitions arose when it was proven that most events lasting 24 h to seven days were associated with cerebral infarction and thus should carry the diagnosis of stroke. This led to a divergence in the North American and World Health Organisation’s view of stroke, one emphasising the evidence of infarction and the other clinical symptoms[4].

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

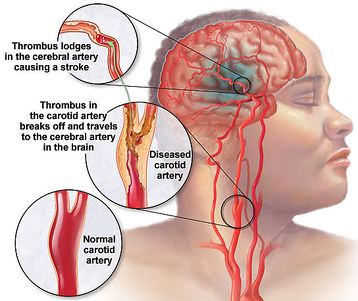

Like ischemic strokes, TIAs are due to locally decreased blood flow to the brain, causing focal neurological symptoms. Decreased blood flow results from either embolism into a cerebral supply artery (from the heart, or the great proximal vessels, extracranial or intracranial arteries, usually affected by atherosclerosis), or in situ occlusion of small perforating arteries.

Resolution of symptoms probably occurs by spontaneous lysis or distal passage of the occluding thrombus or embolus, or by compensation through collateral circulation restoring perfusion into the ischemic brain area.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

TIA subtypes, classified according to the pathophysiological mechanisms are similar to ischemic stroke subtypes. They include [2]

- Large artery atherothrombosis

- Cardiac embolism

- Small vessel (lacunar)

- Cryptogenic (obscure or unknown origin)

- Uncommon subtypes such as vascular dissection, vasculitis etc.

The common risk factors for all TIA include diabetes, hypertension, age, smoking, obesity, alcoholism, unhealthy diet, psychosocial stress, and lack of regular physical activity. A previous history of stroke or TIA will increase substantially the subsequent risk of recurrent stroke or TIA. Among all risk factors, hypertension is the most important one for an individual as well as in a population.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

TIA incidence in a population is difficult to estimate due to other mimicking disorders. Internationally, the probability of a first TIA is around 0.42 per 1000 population in developed countries[5]. TIA incidence in the United States could be around half a million per year, and estimates are about 1.1 per 1000 in the United States population. The estimated overall prevalence of TIA among adults in the United States is approximately 2%[2]. TIAs occur in about 150,000 patients per year in the United Kingdom[6]. It has been shown that previous stroke history increases the prevalence of TIA. Few studies have shown that the majority of people who presented with initial stroke had prior TIA symptoms.

Age[edit | edit source]

The incidence of TIAs increases with age, from 1-3 cases per 100,000 in those younger than 35 years to as many as 1500 cases per 100,000 in those older than 85 years[7]. Fewer than 3% of all major cerebral infarcts occur in children. Paediatric strokes often can have quite different etiologies from those of adult strokes and tend to occur with less frequency.

Gender[edit | edit source]

The incidence of TIAs in men (101 cases per 100,000 population) is significantly higher than that in women (70 per 100,000)[8].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Clinical manifestations will vary, depending on the vessel involved and the cerebral territory it supplies.

The key rule here is that symptoms of TIA should mimic known stroke syndromes, and so depend on the arterial territory involved; see the Stroke page for details

A TIA may last only minutes, therefore symptoms have often resolved before the patient presents to a clinician. Thus, historical questions should be addressed not just to the patient but also to family members or friends who were present at the time of TIA. Witnesses often perceive abnormalities that the patient cannot, such as changes in behaviour, speech, gait, memory, and movement.

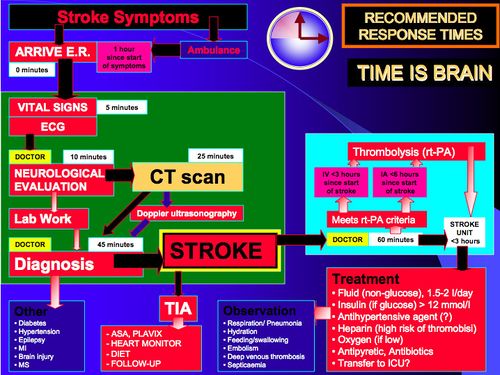

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The main diagnostic challenge of TIA is that the symptoms and signs have usually resolved by the time of assessment[9].

National Stroke Association has established guidelines for TIA evaluation as follows in 2006:[2]

CBC = complete blood count CEA = carotid endarterectomy TCD = Transcranial Doppler TEE = Transesophageal echocardiogram TTE = Transthoracic echocardiogram

ABCD2 score is very important for predicting subsequent risks of TIA or stroke. It provides a more robust prediction standard. The ABCD2 score includes factors including age, blood pressure, clinical symptoms, duration, and diabetes.

- Age: older than 60 years (1 point)

- Blood pressure greater than or equal to 140/90 mmHg on first evaluation (1 point)

- Clinical symptoms: focal weakness with the spell (2 points) or speech impairment without weakness (1 point)

- Duration greater than 60 min (2 points), or 10 min to 59 min (1 point)

- Diabetes mellitus (1 point).

The 2-day risk of stroke was 0% for scores of 0 or 1, 1.3% for 2 or 3, 4.1% for 4 or 5, and 8.1% for 6 or 7.

Most stroke centers will admit patients with TIA to the hospital for expedited management and observation if the score is 4 or 5 or higher.

For those patients who have a lower score, expedited evaluation and management is still warranted. This expedited approach has been proven to improve the outcome

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis of TIA includes but is not limited to[2]

- Vertigo or dizziness

- Seizures

- Headaches, migraine Aura

- Bells palsy

- Drug withdrawal

- dementia

- Electrolyte disorders

- Acute infections

- Alcoholism.

- Stroke

- Meningitis

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Syncope

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Studies addressing the physiotherapists’ role in lifestyle behaviour changes in the TIA population are still lacking. Longitudinal studies are required to provide a more detailed and specific understanding of how to help persons with stroke/TIA make lifestyle behaviour changes. There is a need to further explore what interventions are beneficial.

Physiotherapists play an important role in educating this group of TIA survivors by raising awareness and discussing lifestyle behaviour changes[10][11]. The patient should be educated about the importance of physical activity, blood pressure control, smoking cessation, healthy diet, recognising a stroke and when to seek immediate medical assistance.[2]Compared to healthy individuals, people with TIA in general have lower levels of physical activity [11]. There are higher chances of recurrent stroke in people with stroke or TIA. As inadequate or low levels of physical activity are one of the modifiable risk factors, people with stroke or TIA need additional interventions to improve their physical activity level. In a recent systematic review, it was revealed that lifestyle interventions which specifically encourage increasing physical activity have been proven to be more successful[11]. The inclusion of experts in physical activity and exercise, such as physiotherapists, may be a crucial element for success since a specialised focus on physical activity and/or adding an exercise component to a lifestyle intervention could be advantageous.

This 90 second video gives some good advice regarding exercise post TIA

A TIA can mimic a stroke and up to 10 percent of first-time sufferers often experience full-blown strokes within as little as 90 days. Despite the well-known statistics, no post-TIA regimen exists to help prevent future strokes -- but this might be changing. The most common risk factors for stroke -- hypertension, physical inactivity, elevated lipids, and diabetes -- also are leading risk factors for heart disease.

Researchers found that a modified version of cardiac rehabilitation was effective at reducing some symptoms of stroke in just six weeks following a transient ischemic attack (TIA) often referred to as "mini strokes." No post-TIA regimen exists to help prevent future strokes but researchers say that needs to change. The study showed that participating in a modified version of the second phase of cardiac rehabilitation, which is a well-established program nationwide. This involved 1.5 hour sessions 3 times a week for six weeks. They concluded that all people following TIA should be offered such rehabilitation (and to see their GPs before commencing an exercise program)[13].

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Take home points[1]

- Minor ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack should be managed similarly.

- Making the correct diagnosis of transient ischemic attack is key, as 50% of patients assessed for possible transient ischemic attack will have an alternative diagnosis (ie, are a mimic).

- Atrial fibrillation is a common cause of transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke.

- All patients with possible transient ischemic attack require structural imaging of the brain to rule out mimics.

- Urgent imaging using CT/CT angiography can identify patients at high risk for recurrent stroke.

- Finding out why a transient ischemic attack occurred is the key to preventing a recurrent stroke.

- A cardiac rehabilitation like program would be good to be introduced post TIA and lifestyle modification education.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Coutts SB. Diagnosis and management of transient ischemic attack. Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2017 Feb 3;23(1):82. AVAILABLE FROM: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5898963/ (last accessed 27.12.2019)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Panuganti KK, Tadi P, Lui F. Transient ischemic attack. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Mar 21. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459143/ (last accessed 27.12.2019)

- ↑ Estol CJ (March 1996). "Dr C. Miller Fisher and the history of carotid artery disease". Stroke 27 (3): 559–66.

- ↑ Coupland AP, Thapar A, Qureshi MI, Jenkins H, Davies AH. The definition of stroke. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2017 Jan;110(1):9-12. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0141076816680121 (last accessed 28.12.2019)

- ↑ Truelsen T, Begg S, Mathers C. World Health Organization. The global burden of cerebrovascular disease. Global Burden of Disease 2000

- ↑ Giles MF, Rothwell PM. Risk of stroke early after transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. Dec 2007;6(12):1063-72

- ↑ Kleindorfer D, Panagos P, Pancioli A, et al. Incidence and short-term prognosis of transient ischemic attack in a population-based study. Stroke. Apr 2005;36(4):720-3

- ↑ Bots ML, van der Wilk EC, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Grobbee DE. Transient neurological attacks in the general population. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical relevance. Stroke. Apr 1997;28(4):768-73

- ↑ Sheehan OC, Merwick A, Kelly LA, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of the ABCD2 score to distinguish transient ischemic attack and minor ischemic stroke from noncerebrovascular events: the North Dublin TIA Study. Stroke 2009;40:3449–54

- ↑ The 4th European Congress of the ER-WCPT / Physiotherapy 102S (2016) eS67–eS282 Physio role in TIA Available from: https://www.physiotherapyjournal.com/article/S0031-9406(16)30153-5/pdf (last accessed 27.12.2019)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Hendrickx W, Vlietstra L, Valkenet K, Wondergem R, Veenhof C, English C, Pisters MF. General lifestyle interventions on their own seem insufficient to improve the level of physical activity after stroke or TIA: a systematic review. BMC neurology. 2020 Dec;20(1):1-3.

- ↑ M Dedge Rehab after TIA Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p3EN1uLvbDw (last accessed 27.12.2019)

- ↑ Eureka Alert Indiana U. researcher, hospital, study potential rehab following 'mini stroke' INDIANA UNIVERSITY Available from: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2010-02/iu-iur022310.php (last accessed 27.12.2019)