Hip Dysplasia in Adolescents and Adults: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Hip Dislocation|Dislocation]] or subluxation | |[[Hip Dislocation|Dislocation]] or subluxation | ||

|Iliotibial band friction syndrome | |[[Iliotibial Band Syndrome|Iliotibial band friction syndrome]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Ligamentum Teres|Ligamentum teres]] rupture | |[[Ligamentum Teres|Ligamentum teres]] rupture | ||

|Bursitis: trochanteric, ischial, psoas | |[[Bursitis]]: [[Trochanteric Bursitis|trochanteric]], [[Ischial Bursitis|ischial]], [[Iliopsoas Bursitis|psoas]] | ||

| rowspan="9" |Genitourinary pathology (adnexal torsion, ectopic pregnancy, nephrolithiasis, orchitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, prostatitis, urinary tract infection) | | rowspan="9" |Genitourinary pathology (adnexal torsion, ectopic pregnancy, nephrolithiasis, orchitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, prostatitis, urinary tract infection) | ||

|- | |- | ||

Revision as of 16:11, 18 June 2024

Original Editor - User name

Uploded by - Mahbubur Rahman

Top Contributors - Mahbubur Rahman and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Hip Dysplasia is a term used to describe a variety of abnormalities in which the acetabulum is shallow or incorrectly oriented, and therefore does not properly contain the femoral head.

Hip dysplasia can present in adolescence or adulthood:[1]

A. As a residual diagnosis from infancy –

- a. a patient may have had multiple treatments or surgeries throughout their life and always known their symptoms may worsen at some point, or

- b. it may have been treated and resolved in infancy and been asymptomatic for a number of years, with the patient having no knowledge that symptoms could reoccur in adulthood.

B. As a completely new diagnosis in adolescence or adulthood

Adult hip dysplasia falls into the category of ‘Young adult hip conditions’ which refers to a speciality in orthopedics focusing on hip pathologies in patients from adolescence until those roughly in their 50s. This is due to the differential diagnoses and surgeries around these types of pathologies requiring more specialist input than those of hip pathologies in older adults.

Terms used:

- Hip Dysplasia

- Developmental Dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

- Congenital Dislocation of the hip (CDH)

- “Clicky hips”

- “Loose hips”

- Acetabular Dysplasia

Hip dysplasia both in infancy and adulthood has links with early-onset hip osteoarthritis (OA)[2] [3] [4] [5], therefore timely diagnosis is necessary to provide potential treatment options which can delay the development of OA.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

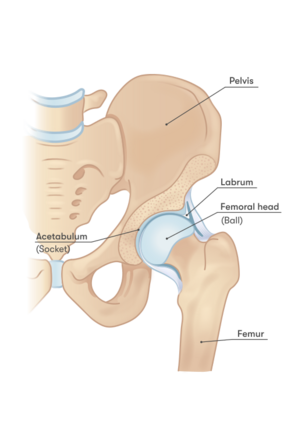

The hip joint is a synovial ball and socket joint, made up of the femoral head, which sits inside the acetabulum. The acetabulum is cup shaped, normally positioned in the pelvis facing antero-laterally. The hip joint capsule consists of circular and longitudinal fibers extending from the rim of the acetabulum, extending to the neck of the femur, and is reinforced by the iliofemoral, pubofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments. The hip joint transmits weight from the trunk to the lower limb and allows for a wide range of movement along with stability created by the joint capsule. The acetabulum and head of the femur are covered in hyaline articular cartilage. The outer rim of the acetabulum is lined with the acetabular labrum. This helps to deepen the acetabulum, absorb shock and creates a suction seal in order to stabilize the femoral head in its socket.[6] [7] The direction of the shaft of the femur in the frontal and horizontal planes also contribute to the stability of the femoral head in the acetabulum. In the horizontal plane, the femur is usually anteverted to approximately 10 degrees in adults.[6]

There is an excellent description of the hip anatomy in a dedicated Physiopedia article for Hip.

Pathology[edit | edit source]

A dysplastic hip consists of a shallow or incorrectly oriented acetabulum, sometimes combined with ligament laxity.[8] [9] This causes unequal loading across the hip joint, and over time the acetabular labrum hypertrophies in order to compensate for the bony deficiency.[10] [11] The labrum is then prone to injury or tear. Subsequently, the suction seal which normally exists in the hip joint is lost, resulting in further instability. In some cases, the femoral shaft is anteverted or retroverted, or the inclination of femoral neck is greater than it should be, causing a ‘coxa valga’.[6]

Due to these pathophysiological mechanisms, secondary hip osteoarthritis develops at a faster rate in a dysplastic hip as compared to a normal hip joint.

Acetabular dysplasia is on a spectrum, ranging from minor abnormalities in the morphology of the joint, through to more severe abnormalities, or even a dislocating hip. It is usually not possible to gauge exactly when OA will begin to develop in a dysplastic hip joint. For some, OA and a need for a Total Hip Replacement (THR) may occur as early as in late adolescence or twenties, if diagnosis has been delayed or prior treatments unsuccessful.[12] For others, it may be the case that less severe or asymptomatic hip dysplasia does not cause a problem or require treatment until much later in life, if at all. Due to patchy reliability of diagnoses amongst this patient cohort, it is difficult to ascertain the rates of diagnosis in relation to the severity of abnormalities.

Acetabular dysplasia has more recently been categorized into 3 patterns: Global, Anterior-superior deficiency, Global deficiency and Posterior-superior deficiency.[13] [14]

| Anterior-superior: | Insufficient anterior wall of the acetabulum. |

| Global/Lateral: | Deficiency of the lateral wall of the acetabulum as well as the anterior and/or/or posterior wall of the acetabulum. |

| Posterior-Superior: | Insufficient posterior wall of the acetabulum, with associated over-coverage of the anterior acetabulum wall. This may be described as acetabular retroversion or as a pincer impingement of the femoral head against the anterior acetabular rim. |

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Hip dysplasia is a common condition. It is the leading cause of hip OA in adults under 60 [16] and is reported as “A significant health concern”. [17]

- Hip dislocations occur in 0.1-0.3% of newborns [18]

- DDH occurs in 1-3% of newborns [19]

- 80% of cases are female [18]

- Over 50% of those with DDH have positive family history [20]

- 92% of young adult THRs due to OA from hip dysplasia had no reported hip instability in infancy. [21]

- Percentage of Total Hip Replacements (THRs) due to OA secondary to hip dysplasia: A. 1 in 10 THRs in total [17] B. 29% of THRs under 60 [22] C. 26 – 31% of THRs under 40 [21]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

It is not fully understood why acetabular dysplasia can occur or re-occur in adolescence or adulthood. It is suggested that it could be down to milder cases being missed in infancy, or that a growth spurt in adolescence could play a part in the development of an incongruency between the acetabulum and femoral head.[1]

The risk factors for infant DDH are described in the etiology part of Hip Dysplasia page.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

For young adults presenting with hip pain, a range of pathologies can be held in mind. It is mainly grouped into intra-articular, extra-articular and non-musculoskeletal pathologies. In the below table provides the details about the possible conditions may produce hip pain.[23]

| Intra-articular | Extra-articular | Non-musculoskeletal |

|---|---|---|

| Femoroacetabular impingement | Athletic pubalgia/sports hernia | Intra-abdominal pathology (inguinal or femoral hernia, abdominal aortic aneurysm, appendicitis, diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, lymphadenitis) |

| Labral tears | Osteitis pubis | |

| Chondral defect | Muscular pathology: strains or tendinopathies | |

| Loose bodies | Snapping hip (internal or external) | |

| Osteoarthritis | Ischiofemoral or trochanteric-pelvic impingement | |

| Developmental hip dysplasia | Capsular laxity | |

| Traumatic femoral head or neck fracture | Piriformis syndrome | |

| Dislocation or subluxation | Iliotibial band friction syndrome | |

| Ligamentum teres rupture | Bursitis: trochanteric, ischial, psoas | Genitourinary pathology (adnexal torsion, ectopic pregnancy, nephrolithiasis, orchitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, prostatitis, urinary tract infection) |

| Femoral neck stress fracture | Psoas abscess | |

| Capsular laxity | Pubic ramus fracture (traumatic or stress fracture) | |

| Avascular necrosis | Apophyseal avulsion fracture (anterior-superior iliac spine, iliac crest, anterior-inferior iliac spine, pubis, ischial tuberosity, greater trochanter, lesser trochanter) | |

| Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease | ||

| Slipped capital femoral epiphysis | Lumbar spine pathology | |

| Transient synovitis | Referred knee pain | |

| Septic arthritis | Peripheral nerve compression (genitofemoral, iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, lateral femoral cutaneous, obturator, or pudendal nerves) | |

| Pigmented villonodular synovitis |

Another popular method to assessment of different pathological condition of Hip Joint is The Layer Concept. In which the assessment of the hip and pelvis are considered in the four layers: Osteochondral, Inert, Contractile and Neuromechanical.

Layer 1, the Osteochondral layer, refers to the bony joint structures such as the femur, acetabulum and innominate bones.

Layer 2, the inert layer, includes the hip joint capsule, labrum, ligamentum teres and ligamentous complex.

Layer 3 is the contractile layer, which consists of the musculature of the hip, lumbosacral complex and pelvic floor.

Layer 4 is the neuromechanical layer, which encompasses the neural and vascular structures, regional mechanoreceptors, and the kinematic chain of the thoraco-lumbar and lower extremity mechanics.[24]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The literature describes the following clinical physiology and aspects of how a patient with hip dysplasia might present:

- Recurring hip, groin or lateral hip pain

- C-sign pain

- Labral symptoms e.g. hip locking, catching, clicking, giving way

- Positive impingement test

- Knee pain (with or without hip pain)

- Back pain

- Pelvic pain

- Good range of movement (ROM), sometimes hypermobile

- Instability & associated muscle tendon pain due to compensating muscle patterning

- Trendelenburg gait

- Overdeveloped or overactive hip flexors

- Hyper lordosis, anterior pelvic tilt

- Femoral anteversion & lateral rotation of tibia

- Smaller glute med – weak hip abductors

- Can be subtle/manageable at first & very slowly worsen over a number of years, or suddenly deteriorate.[25] [26] [27] [8] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34]

The overall picture can be of an unstable hip joint, and compensating postural and muscular adaptations, sometimes with symptoms suggesting labral pathology.

A patient with hip dysplasia may well exhibit a Trendelenburg gait due to hip abductor weakness. If they have lived for longer with hip pain or with a residual diagnosis of hip dysplasia from infancy, the bony trabeculae in their hip joints may have adapted to the unequal stresses placed on them which is described in detail in another PhysioPedia Page. The compensating muscular patterning such as overactive hip flexors may have developed due to a deficiency in the anterior acetabular wall of the affected hip or hips, and the pelvis tilting anteriorly to compensate for that.

In some cases, acetabular dysplasia can present in a similar way to Femoro-Acetabular impingement, and these conditions can also coincide. Given that the morphology and treatment pathway differ for these conditions, a suspected diagnosis of either of these may need to be confirmed by accurately interpreted x-ray.[38] [39]

Special Test[edit | edit source]

There is no one single diagnostic test which can indicate the presence of acetabular dysplasia. Clusters of tests can be helpful in building a clinical picture. Please note these tests have varying specificity and diagnostic accuracy. Some tests may be useful in the assessment of young adult hip pain could include:

- Trendelenburg sign

- FADDIR

- Fitzgerald test[27]

More information is available in the Provocative Test part of the Hip Labral Disorder page.

Some tests which could be used to assess for hip instability are described as follows:[40]

- Log roll

- FABER test

- Prone instability test

- Abduction-Hyperextension-External Rotation (AB-HEER) Test

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis is made using a combination of clinical signs and symptoms along with x-ray.[26] [28]

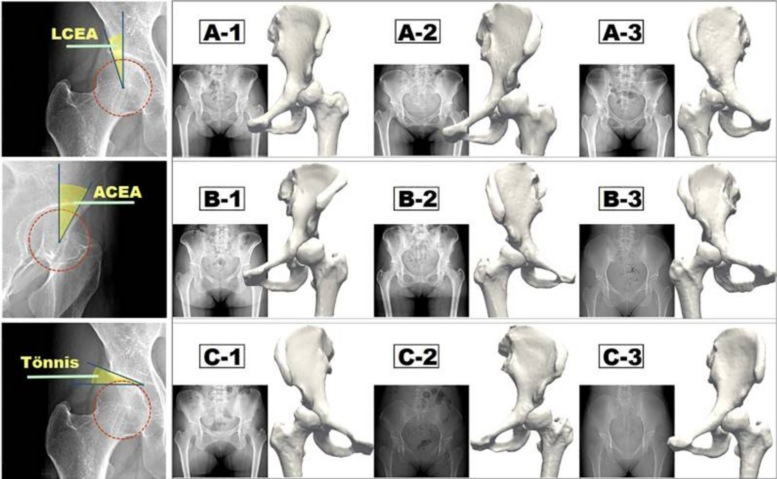

A plain AP pelvis x-ray can be used to measure the following:

Lateral Centre Edge Angle (LCEA): This is the angle between a horizontal line through the centre of the femoral head and the lateral edge of the acetabulum. With Acetabular dysplasia the lateral CEA is <18°, with 18° - 25° discussed as being ‘borderline’ dysplasia.[41]

Acetabular index (weight bearing zone): This measures the inclination of the roof of the acetabulum. In most normal hips the acetabular index is 3° – 13°. An angle of >14° is usually indicative of acetabular dysplasia.[42]

Femoral head anterior/posterior coverage: This looks at the percentage of coverage of the anterior and posterior femoral head.[42]

Anterior CEA: There is somewhat a lack of consensus around cases of borderline dysplasia, which causes a challenge when decisions need to be made about treatment. In these cases, a false profile x-ray may also be taken to measure anterior CEA.[41]

Treatment options[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatment:

- Physiotherapy – discussed in more detail below

- Painkillers and anti-inflammatory medication

- Weight management

- Work and lifestyle adaptations

- Non-impact sports

Surgical options:

- Hip Arthroscopy can be used in some cases as a diagnostic tool, however, in most cases a diagnosis of hip dysplasia can occur with imaging alone. Arthroscopy and labral debridement is usually only recommended in cases of borderline dysplasia, and with extreme caution, as it has the potential to increase instability in the hip joint and result in poorer outcomes for the patient.[43] [44] [45] [46]

- Pelvic Osteotomy can be used to correct the underlying structural abnormality present in hip dysplasia (54). This is discussed in more detail below.This is a well-established hip preservation surgery which re-orientates the acetabulum to create a better hip socket for containment of the femoral head. It’s aims are to improve pain and function and delay the need for THR. There are two main pelvic osteotomy surgeries used to treat adult hip dysplasia. First one is the Peri-acetabular Osteotomy (PAO), also known as the Ganz or Bernese Osteotomy as slight variation of that technique; and second one is the Triple Pelvic Osteotomy (TPO) also known as the Birmingham Interlocking Pelvic Osteotomy (BIPO). The surgery is preventative; ideally undertaken when symptoms are mild (but not asymptomatic), and when there is no OA present in the joint. There have been very good outcomes seen from pelvic osteotomy at 20–30 year follow-up. (55, 56, 57, 58) Although the evidence base for PAO surgeries is a level 3 prognostic study, it shows a good success rate for appropriately selected patients.

- Femoral osteotomy is used in some cases in which the femur is anteverted or retroverted and contributes to hip deformity. This can be used on its own or alongside a pelvic osteotomy (55).

- Total Hip Replacement (THR) is normally the surgical treatment used when hip OA has advanced, is significantly impacting on a patient’s quality of life, and can no longer be treated by a hip preservation procedure such as pelvic osteotomy (30).

Difficulties with diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Study found that the average time to diagnosis of acetabular dysplasia was 5 years (range 5 months – 29 years) with up to 11 health professionals visited before diagnosis was made.[25] It is noted that it is frequently missed on x-rays by those who lack experience with diagnosis of hip dysplasia.[40]

Anecdotally, there are large numbers of stories with this patient cohort describing the reasons for the diagnostic delay. Some describe subtle symptoms to begin with which would seem to correlate with a muscular injury and only occurring with exercise. There seems to be a reluctance at times of health professionals to refer to imaging or referring for MRI rather than x-ray. In some cases, a labral tear is diagnosed and surgically treated, but without treating the underlying bony morphology causing this, further problems can be caused.[46] Sadly, there are also cases in which patients have not felt believed when reporting their symptoms, diagnosed with a persistent unexplained pain, or even referred for psychiatric input.

The consequences of this delay in diagnosis can be significant. A patient’s pain and mobility may worsen, with a domino effect of visiting multiple health professionals in search of an answer, with loss of trust in health professionals. Worsening mobility can hinder a patient’s ability to work, and there is an impact on their family and dependents, their mental health and their ability to manage financially. Without timely diagnosis and treatment, there is potentially the need for early THR.[12]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

For adolescent or adult patients presenting in the physiotherapy clinic with hip-related pain, consideration needs to be given to differential diagnosis. For those patients showing objective markers of hip instability, management may need to focus on strengthening core and hip stabilizers and treatment of compensating muscle patterning.

For those displaying symptoms of atraumatic labral pathology, it may be wise to have in consideration a potential underlying morphology which has preceded this, including a Femoro-Acetabular impingement or Acetabular Dysplasia.[46]

Due to the trajectory of the condition, the nature of how symptoms can progress, and the difficulties often found in ascertaining definitive diagnosis, caution may need to be taken with patients with recurring symptoms of hip-related pain and repeat referrals for physiotherapy management. It could be that their symptoms were manageable for some time with conservative treatment before beginning to worsen, or it could be that they have not yet been able to ascertain a definitive diagnosis for their hip pain.

Guidance from the British Hip Society states that if there is no improvement in symptoms after physiotherapy input, and particularly if symptoms are impacting a patient’s activities of daily living, it is recommended that they are referred for an x-ray and to a specialist in young adult hip conditions. MRI scan and/or CT scan may be performed at a later stage.[26] [28]

For those with a known diagnosis of acetabular dysplasia, and who are wanting to pursue a conservative treatment approach prior to or instead of surgery, it can be helpful to utilize closed-kinetic chain exercises to improve proprioception, and correction of postural adaptations where necessary in order to alter the loading patterns placed on the hip to reduce pain.[48] Some helpful therapeutic exercise interventions are discussed in the literature. Progressive resistance training, hip abductor strengthening and core stability exercises are described.[49] [50] [51] Treatment needs to be individualized.[49] Therapy and exercise techniques which cause increased pain severity or irritability should be avoided or adapted.

Sensitive and respectful support for weight management may need to be considered in some cases,[49] with acknowledgement of the difficulties in maintaining an active lifestyle when pain and mobility issues are present.

Painkillers and anti-inflammatory drugs can assist in managing pain and it may be helpful for a patient to consider making adaptations at work, especially if employed in a physical or active role.

Non-impact sports such as Pilates, swimming or cycling can be of benefit in maintaining healthy activity levels. Some may find that with adaptations they may be able to continue with impact sports such as running, whilst others may find this worsens their symptoms.

For those who’s mobility and function have been more greatly affected, a wider MDT approach may need to be adopted, with consideration for walking aids and equipment or adaptations in the home.

The evidence base around physiotherapy management of adult hip dysplasia is severely lacking, but our understanding of this is growing. The articles above consist of level 4 case series and feasibility studies, which – although low levels of evidence – help to provide some insight into where the direction of future research in this area could take us.

A diagnosis of hip dysplasia brings with it the crucial need for education and advice to aid understanding of the condition, its trajectory and the available treatment options. The psychological impact of receiving this diagnosis cannot be underestimated.[34] As physiotherapists, we are ideally placed to facilitate a patient’s understanding and management of this lifelong condition.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- International Hip Dysplasia Institute.

- Commissioning Guide: Pain Arising from the Hip In Adults.

- Management of Adult Hip Dysplasia by British Hip Society.

- Hip Dysplasia in teenagers & young adults by Royal National Orthopedic Hospital.

- Rehabilitation Guidelines by Royal National Orthopedic Hospital.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pun S. Hip dysplasia in the young adult caused by residual childhood and adolescent-onset dysplasia. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine [Internet]. 2016 Sep 9;9(4):427–34.

- ↑ Jacobsen S, Sonne-holm S, Søballe K, Gebuhr P, Lund B. Hip dysplasia and osteoarthrosis. Acta Orthopaedica. 2005 Jan;76(2):149–58.

- ↑ Kaya M, Suzuki T, Emori M, Yamashita T. Hip morphology influences the pattern of articular cartilage damage. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2014 Sep 11;24(6):2016–23.

- ↑ Reijman M, Hazes JMW, Pols HAP, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Acetabular dysplasia predicts incident osteoarthritis of the hip: The Rotterdam study. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2005;52(3):787–93.

- ↑ Wyles CC, Heidenreich MJ, Jeng J, Larson DR, Trousdale RT, Sierra RJ. The John Charnley Award: Redefining the Natural History of Osteoarthritis in Patients With Hip Dysplasia and Impingement. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2017 Feb 1;475(2):336–50.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Palastanga N, Soames R. Anatomy and Human Movement: Structure and Function. 6th ed. London: Elsevier; 2012. (page 287-8; page 295-6)

- ↑ Kuntzman AJ, Tortora GJ. Anatomy and Physiology for the Manual Therapies. John Wiley & Sons; 2010. (page 244-5)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Muldoon M, Gosey G, Healey R, Santore R. Hypermobility: a Key Factor in Hip Dysplasia. A Prospective Evaluation of 266 Patients. Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery. 2016 Sep;3(suppl_1).

- ↑ Ayanoğlu S, Çabuk H, Kuşku Çabuk F, Beng K, Yildirim T, Uyar Bozkurt S. Greater presence of receptors for relaxin in the ligamentum teres of female infants who undergo open reduction for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research [Internet]. 2021 Oct 18;16(1).

- ↑ Hartig-Andreasen C, Søballe K, Troelsen A. The role of the acetabular labrum in hip dysplasia. Acta Orthopaedica [Internet]. 2013 Feb 1;84(1):60–4.

- ↑ Klaue K, Durnin C, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome. A clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery British volume. 1991 May;73-B(3):423–9.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Pallante GD, Statz JM, Milbrandt TA, Trousdale RT. Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty in Patients 20 Years Old and Younger. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2020 Jan 22;102(6):519–25.

- ↑ Nepple JJ, Wells J, Ross JR, Bedi A, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Three Patterns of Acetabular Deficiency Are Common in Young Adult Patients With Acetabular Dysplasia. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 2017 Apr;475(4):1037–44.

- ↑ Wilkin GP, Ibrahim MM, Smit KM, Beaulé PE. A Contemporary Definition of Hip Dysplasia and Structural Instability: Toward a Comprehensive Classification for Acetabular Dysplasia. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2017 Sep;32(9):S20–7.

- ↑ Tom Goom. 3 types of hip dysplasia and how to identify them with Tom Goom. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rWgd0jaSYXs [last accessed 18/6/2024]

- ↑ Jacobsen S, Stig Sonne-Holm. Hip dysplasia: a significant risk factor for the development of hip osteoarthritis. A cross-sectional survey. Rheumatology. 2005 Feb 1;44(2).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Agostiniani R, Atti G, Bonforte S, Casini C, Cirillo M, De Pellegrin M, et al. Recommendations for early diagnosis of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH): working group intersociety consensus document. Italian Journal of Pediatrics [Internet]. 2020 Oct 9;46(1).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Kotlarsky P, Haber R, Bialik V, Eidelman M. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: What has changed in the last 20 years? World Journal of Orthopedics [Internet]. 2015;6(11):886.

- ↑ Sewell MD, Rosendahl K, Eastwood DM. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. BMJ. 2009 Nov 24;339(nov24 2):b4454–4.

- ↑ Lee CB, Mata-Fink A, Millis MB, Kim YJ. Demographic Differences in Adolescent-diagnosed and Adult-diagnosed Acetabular Dysplasia Compared With Infantile Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2013 Mar;33(2):107–11.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Engesæter IØ, Lehmann T, Laborie LB, Lie SA, Rosendahl K, Engesæter LB. Total hip replacement in young adults with hip dysplasia: age at diagnosis, previous treatment, quality of life, and validation of diagnoses reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register between 1987 and 2007. Acta Orthopaedica. 2011 Mar 24;82(2):149–54.

- ↑ Ove Furnes, Stein Atle Lie, Birgitte Espehaug, Stein Emil Vollset, Engesæter LB, Leif Ivar Havelin. Hip Disease and the Prognosis of Total Hip replacements. a Review of 53,698 Primary Total Hip Replacements Reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. The Journal of Bone and Joint surgery. 2001 May 1;83(4).

- ↑ Trofa DP, Mayeux SE, Parisien RL, Ahmad CS, Lynch TS. Mastering the Physical Examination of the Athlete’s Hip. American Journal of Orthopedics (Belle Mead, NJ) [Internet]. 2017;46(1):10–6.

- ↑ Draovitch P, Edelstein J, Kelly BT. The Layer concept: Utilization in Determining the Pain generators, Pathology and How Structure Determines Treatment. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2012 Feb 28;5(1):1–8.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Nunley RM, Prather H, Hunt D, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Clinical Presentation of Symptomatic Acetabular Dysplasia in Skeletally Mature Patients. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2011 May 4;93(Supplement_2):17–21.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Nolan J, McBride D, Fitch J, Rehill J, Creamer P, Smeatham A, et al. Commissioning Guide: Pain Arising from the Hip in Adults [Internet]. British Orthopaedic Association. 2017 [cited 2024 Jun 15].

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Reiman MP, Mather RC, Cook CE. Physical Examination Tests for Hip Dysfunction and Injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015 Mar;49(6):357–61.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 J. Kraeutler M, Garabekyan T, Pascual-Garrido C, Mei-Dan O. Hip instability: a Review of Hip Dysplasia and Other Contributing Factors. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2016;6(3).

- ↑ Jacobsen JS, Hölmich P, Thorborg K, Bolvig L, Jakobsen SS, Søballe K, et al. Muscle-tendon-related Pain in 100 Patients with Hip dysplasia: Prevalence and Associations with self-reported Hip Disability and Muscle Strength. Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery [Internet]. 2018 Jan 1;5(1):39–46. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jhps/article/5/1/39/4638269

- ↑ Babst D, Steppacher SD, Ganz R, Siebenrock KA, Tannast M. The Iliocapsularis Muscle: an Important Stabilizer in the Dysplastic Hip. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 2011 Jun;469(6):1728–34.

- ↑ Fukushima K, Miyagi M, Inoue G, Shirasawa E, Uchiyama K, Takahira N, et al. Relationship between Spinal Sagittal Alignment and Acetabular coverage: a patient-matched Control Study. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery [Internet]. 2018 Nov 1 [cited 2024 Jun 15];138(11):1495–9.

- ↑ Lerch TD, Liechti EF, Todorski IAS, Schmaranzer F, Steppacher SD, Siebenrock KA, et al. Prevalence of Combined Abnormalities of Tibial and Femoral Torsion in Patients with Symptomatic Hip Dysplasia and Femoroacetabular Impingement. The Bone & Joint Journal [Internet]. 2020 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Jun 15];102-B(12):1636–45.

- ↑ Liu R, Wen X, Tong Z, Wang K, Wang C. Changes of Gluteus Medius Muscle in the Adult Patients with Unilateral Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012 Jun 15;13(1).

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Gambling TS, Long A. Psycho-social Impact of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip and of Differential Access to Early Diagnosis and treatment: a Narrative Study of Young Adults. SAGE Open Medicine. 2019 Jan;7:1–13.

- ↑ Tom Goom. Hip dysplasia key signs and symptoms with Tom Goom. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6bIC3z9Ilmk [last accessed 18/6/2024]

- ↑ Benoy Mathew. Hip DYSPLASIA - Interview with Mr. Jonathan Hutt. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PQr6Gw2ha_o [last accessed 6/15/2024]

- ↑ Benoy Mathew. Adult Hip Dysplasia (Ben & Glen Podcast). Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hk-it-iTYw [last accessed 6/15/2024]

- ↑ Mimura T, Mori K, Furuya Y, Itakura S, Kawasaki T, Imai S. Prevalence and Morphological Features of Acetabular Dysplasia with Coexisting Femoroacetabular impingement-related Findings in a Japanese population: a Computed tomography-based cross-sectional Study. Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery. 2018 Mar 12;5(2):137–49.

- ↑ Nepple JJ, Clohisy JC. The Dysplastic and Unstable Hip. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review. 2015 Dec;23(4):180–6.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 P. Reiman M. Clinical Examination of Hip Dysplasia/Instability. Swiss Sports & Exercise Medicine [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2024 Jun 15];66(4):8–12.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Chen S, Zhang L, Mei Y, Zhang H, Hu Y, Chen D. Role of the Anterior Center-Edge Angle on Acetabular Stress Distribution in Borderline Development Dysplastic of Hip Determined by Finite Element Analysis. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Jun 15];10.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Tannast M, Hanke MS, Zheng G, Steppacher SD, Siebenrock KA. What Are the Radiographic Reference Values for Acetabular Under- and Overcoverage? Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 2015 Apr;473(4):1234–46.

- ↑ Kirsch JM, Khan M, Bedi A. Does Hip Arthroscopy Have a Role in the Treatment of Developmental Hip Dysplasia? The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2017 Sep;32(9):S28–31.

- ↑ Larson CM, Ross JR, Stone RM, Samuelson KM, Schelling EF, M. Russell Giveans, et al. Arthroscopic Management of Dysplastic Hip Deformities: Predictors of Success and Failures with Comparison to an Arthroscopic FAI Cohort. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015 Nov 30;44(2):447–53.

- ↑ Ricciardi BF, Fields KG, Wentzel C, Kelly BT, Sink EL. Early Functional Outcomes of Periacetabular Osteotomy after Failed Hip Arthroscopic Surgery for Symptomatic Acetabular Dysplasia. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017 Jun 15;45(11):2460–7.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Yeung M, Kowalczuk M, Simunovic N, Ayeni OR. Hip Arthroscopy in the Setting of Hip dysplasia: a Systematic Review. Bone & Joint Research. 2016 Jun;5(6):225–31.

- ↑ stepscharity. Natalie's Story - Late diagnosis of Hip Dysplasia. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kN6-03liWAI [last accessed 16/6/2024]

- ↑ Soper-Doyle H, Sharp MJ. Hip Dysplasia in Teenagers & Young Adults [Internet]. 45 Bolsover Street, London, W1W 5AQ : Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Trust - Outpatient Assessment Centre; [cited 2024 Jun 17].

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Jacobsen JS, Thorborg K, Sörensen D, Jakobsen SS, Nielsen RO, Oestergaard LG, et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of a six-month Exercise and Patient Education Intervention for Patients with Hip dysplasia: a Mixed Methods Study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2022 Oct 1;61(102615):102615–5.

- ↑ Kuroda D, Maeyama A, Naito M, Moriyama S, Yoshimura I, Nakamura Y, et al. Dynamic Hip stability, Strength and Pain before and after Hip Abductor Strengthening Exercises for Patients with Dysplastic Hips. Isokinetics and Exercise Science. 2013 May 20;21(2):95–100.

- ↑ Mortensen L, Schultz J, Elsner A, Jakobsen SS, Søballe K, Jacobsen JS, et al. Progressive Resistance Training in Patients with Hip dysplasia: a Feasibility Study. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2018;50(8):751–8.

- ↑ Tom Goom. Hip dysplasia treatment with Tom Goom. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R296RXesDx4 [last accessed 18/6/2024]