Lymphoedema: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

* Fibrosis | * Fibrosis | ||

* Skin changes | * Skin changes | ||

* During this stage papillomas may form, infections/cellulitis may occur, and the skin becomes dry | * During this stage papillomas may form, infections/cellulitis may occur, and the skin becomes dry<u></u> | ||

== Evaluation == | == Evaluation == | ||

Lymphedema is often confused with other causes of extremity edema and enlargement. | Lymphedema is often confused with other causes of extremity edema and enlargement. | ||

| Line 187: | Line 186: | ||

** Light massage as needed | ** Light massage as needed | ||

Contraindications for compression includes arterial disease, painful postphlebitic syndrome, and occult visceral neoplasia.<ref name="three" /><sup><br></sup> | Contraindications for compression includes arterial disease, painful postphlebitic syndrome, and occult visceral neoplasia.<ref name="three" /><sup><br></sup>Complete Decongestive Therapy ( 109 seconds) | ||

{{#ev: youtube | M9uhzBQoO98 | 300}} | {{#ev: youtube | M9uhzBQoO98 | 300}}Manual Lymphatic Drainage 3 minutes 51 seconds{{#ev: youtube | dT6rAL4-D14 | 300}}Self care - Lympathedema (3 minutes 20 seconds){{#ev: youtube | x8k1pLVREEA | 300}} | ||

{{#ev: youtube | dT6rAL4-D14 | 300}} | |||

{{#ev: youtube | x8k1pLVREEA | 300}} | |||

{{#ev: youtube | t_6B_Vc-73s | 300}} | {{#ev: youtube | t_6B_Vc-73s | 300}} | ||

{{#ev: youtube | grS-Sgfh3vw | 300}} | {{#ev: youtube | grS-Sgfh3vw | 300}} | ||

Revision as of 07:40, 28 July 2020

Original Editors - Emily Clark from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Emily Clark, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Manali K Shah, Fasuba Ayobami, Vidya Acharya, Essam Ahmed, Candace Goh, Kim Jackson, Jonathan Wong, Elaine Lonnemann, Chelsea Mclene, 127.0.0.1 and Wendy Walker

Introduction[edit | edit source]

- Lymphedema is a chronic disease marked by the increased collection of lymphatic fluid in the body, causing swelling, which can lead to skin and tissue changes.

- The chronic, progressive accumulation of protein-rich fluid within the interstitium and the fibro-adipose tissue exceeds the capacity of the lymphatic system to transport the fluid.

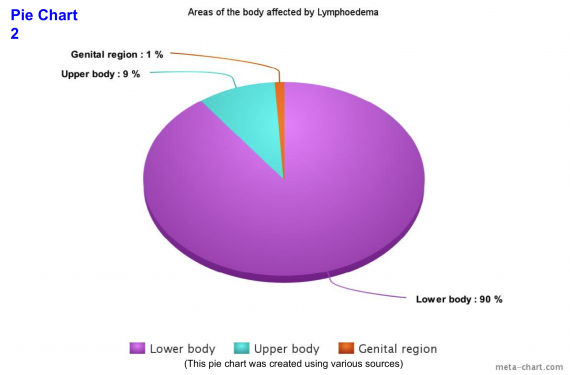

- Swelling associated with lymphedema can occur anywhere in the body, including the arms, legs, genitals, face, neck, chest wall, and oral cavity.

- There are many psychological, physical, and social sequelae related to a diagnosis of lymphedema.

- Lymphedema is classified as either (genetic) primary lymphedema or (acquired) secondary lymphedema[1].

Signs and symptoms of lymphedema include

- Distal swelling in the extremities including the arms, hands, legs, feet; swelling proximally in the breast, chest, shoulder, pelvis, groin, genitals, face/intraoral tissues

- Restricted range of motion in the joints because of swelling and tissue changes

- Skin discoloration

- Pain and altered sensation

- Limb heaviness;

- Difficulty fitting into clothing[1].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

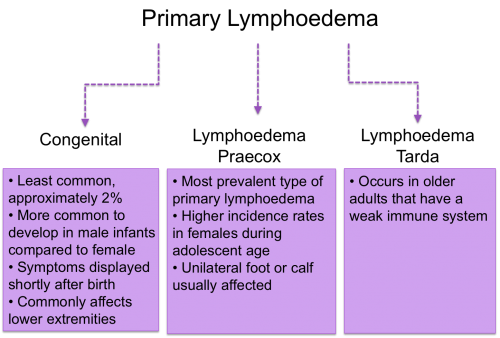

Primary lymphedema is an inherited or congenital condition that causes a malformation of the lymphatics system, most often because of genetic mutation. Primary lymphedema: subdivided into 3 categories:

- Congenital lymphedema, present at birth, or recognized within two years of birth;

- Lymphedema praecox, occurring at puberty or the beginning of the third decade;

- Lymphedema tarda, which begins after 35 years of age.

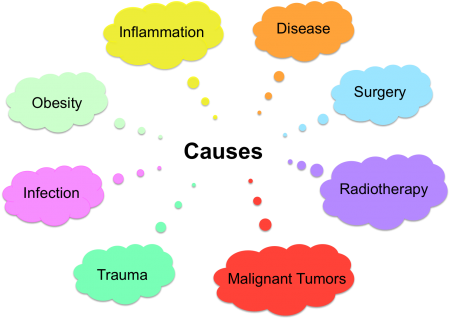

Secondary lymphedema results from insult, injury, or obstruction to the lymphatic system.

- Most common cause of lymphedema worldwide is filariasis caused by infection by Wuchereria bancrofti

- In developed countries, most secondary lymphedema cases are due to malignancy or related to the treatment of malignancy. This includes surgical excision of lymph nodes, local radiation treatment, or medical therapy.

- Breast cancer is the most common cancer associated with secondary lymphedema in developed countries[1].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Primary lymphedema is rare, affecting 1 in 100,000 individuals.

Secondary lymphedema is the most common cause of the disease and affects approximately 1 in 1000 Americans[1].

The identification of the incidence and prevalence of lymphedema is complex.

- Lymphedema is remarkably prevalent, but the population implications of lymphatic dysfunction are not well studied. Prevalence estimates for lymphedema are relatively high, yet its prevalence is likely underestimated.

The incidence of lymphedema is most widely studied in the oncologic population.

- One in 5 women who survive breast cancer will develop lymphedema.

- In head and neck cancer, lymphatic and soft tissue complications can develop throughout the first 18 months post-treatment, with greater than 90% of patients experiencing some form of internal, external, or combined lymphedema. Over half of those patients developing fibrosis.

- In one recent study, 37% of women treated for gynecological cancer had measurable evidence of lymphedema within 12 months post-treatment.

- In the gynecologic oncologic population, more extensive lymph node dissection, receipt of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, increasing body mass index, insufficient levels of physical activity, a diagnosis of vulvar/vaginal cancer, and presence of pre-treatment lymphedema were identified as potential risk factors to lymphedema development[1].

- Cellulitis is a one of the leading causes in developing lymphoedema. In 2003-2004 there were 45,522 cellulitis admissions reported by the NHS.[2]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Primary lymphedema

- Associated with dysplasia of the lymphatic system and can also develop with conditions of other vascular abnormalities, including Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome, and Turner syndrome.

- Primary lymphedema is marked by hyperplasia, hypoplasia, or aplasia of the lymphatic vessels.

Secondary lymphedema

- Develops due to damage or dysfunction of the normally functioning lymphatic system.

- Although cancer treatments, including oncologic surgical procedures such as axillary lymph node dissection and excision in breast cancer and radiation treatment, are the most common cause of lymphedema in the United States, filariasis is the most common cause of secondary lymphedema globally.

- Filariasis is the direct infestation of lymph nodes by the parasite, Wuchereria bancrofti. The spread of the parasite by mosquitos affects millions of people in the tropic and subtropic regions of Asia, Africa, Westen Pacific, and Central and South America.

- Oncologic surgical procedures such as sentinel lymph node biopsy and radical dissection that require excision of regional lymph nodes or vessels can lead to the development of secondary lymphedema.

- Other surgical procedures linked to secondary lymphedema development include peripheral vascular surgery, burn scar excision, vein stripping, and lipectomy.

Nonsurgical causes of lymphedema include

- Recurrent tumors or malignancy that have metastasized to the lymph nodes

- Obstructive lesions within the lymphatic system

- Infected and/or traumatized lymphatic vessels

- Scar tissue obliterating the lumen of the lymphatic vessels.

- Edema from deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or nonobstructive causes of chronic venous insufficiency at the extremities may lead to secondary lymphedema.

Although there is no definitive cure for lymphedema, with proper diagnosis and management, its progression and potential complications can successfully be managed[1].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

There are both physical and psychological effects of the chronic condition[3][4]. Early diagnosis is vital to ensure the correct treatment is chosen.

Physical Changes

- Swelling in an arm or a leg. It may be the entire limb or only parts . Most likely unilateral, but can be bilateral

- In the early stages pitting oedema occurs where the skin is pressed leaving an indent in the swelling. Elevating the arm creates a draining effect to reduce swelling

- Can be fibrosis, pitting edema

- Limbs can feel heavy and achy

- There is altered sensation, for example, pins and needles, burning

- Reduced mobility and range of movement of the affected limb/s

- Pain and joint discomfort

- Skin changes, for example redness and increased temperature

- Nail discoloration[5]

- Hyperkeratosis (thickening of the skin) and lymphangiectasia (dilated superficial lymph vessels)[6]

- Reoccurring infections in the involved limb

- Hardening, thickening, or tightness of the skin[7][8]

- Loss of hair

- Loss of sleep[9]

- Symptoms can increase during warm weather, menstruation, and if the limb has been left in its depended position.[10]

- If primary and affecting the intestine signs and symptom include; abdominal bloating, diarrhea, and intolerance of fatty foods.[8]

When the condition affects the lower extremities, over time the affected person’s gait pattern is altered, leading to a higher risk of disability. The pictures below show how lymphodema can appear in the lower limbs.

Psychological Effects

There are psychological effects associated with the condition as a result of changes to body image.

- Swelling and weight gain impact physical appearance that can affect one’s perception of how they look, consequently decreasing their self-confidence [11][4]

- People commonly detach themselves from social events with family and friends leading to social isolation[12]

- Disturbed sleeping pattern

- Some people may feel they have a lack of support

- Financial concerns as a consequence of treatment cost and potential job loss/change[12]

- Some cancer survivors that have acquired secondary lymphoedema feel that it can be a constant reminder of previously having cancer[13]

- For those that experience unilateral lymphoedema, commonly different sizes of garmets have to be worn on each side of the body and oversized clothes have to be worn because items such as jeans dont fit the limbs[13]. Psychologically this can largely impact the person because they may not feel comfortable with the way they look and therefore exclude themselves from public situations

Stages of Lymphoedema[edit | edit source]

Lymphedema Stages

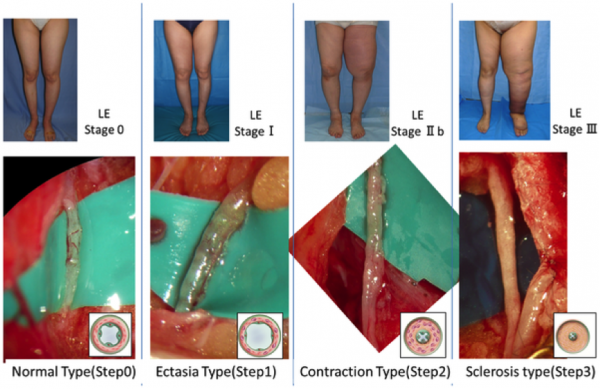

Stage 0 (Latency stage)

- The patient is considered “at-risk” for lymphedema development due to injury to the lymphatic vessels but does not present with outward signs of edema.

- Includes patients with breast cancer who have undergone sentinel lymph node biopsy and or radiation but have not yet developed swelling.

- Lymphatic transport capacity has been reduced, which predisposes the patient to lymphatic overload and resultant edema.

Stage 1 (Spontaneous)

- Reversible

- Has pitting edema

- Swelling at this stage is soft, and may respond to elevation

Stage 2 (Spontaneously irreversible)

- Has tissue fibrosis/induration

- Swelling does not respond to elevation

- Skin and tissue thickening occurs as the limb volume increases

- Pitting may be present, but may be difficult to assess due to tissue and or skin fibrosis

Stage 3 (Lymphostatic elephantiasis)

- Show the following:

- Pitting edema

- Fibrosis

- Skin changes

- During this stage papillomas may form, infections/cellulitis may occur, and the skin becomes dry

Evaluation[edit | edit source]

Lymphedema is often confused with other causes of extremity edema and enlargement.

- Understanding the risk factors and physical examination signs of lymphedema can accurately diagnose patients about 90% of the time.

- Correct diagnosis is imperative so patients can be managed appropriately.

- Diagnosis is suspected by evaluating the history and physical examination.

- Lymphoscintigraphy confirms the diagnosis.

- Imaging is unnecessary to make the diagnosis but can be used as confirmation, assessment of the extent of involvement, and help to determine therapeutic intervention.

Newer technologies include 3-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computerized tomography (CT), ultrasound, and bioelectrical impedance analysis. Ultrasound is useful to exclude other etiologies like DVT, venous insufficiency and can also help in identifying tissue changes and masses that might be the cause of lymphatic compression. CT and MRI can investigate soft tissue edema with good sensitivity and specificity, but they are relatively expensive.[1]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Lymphedema can cause

- Thickening of the dermis and can create ulcerations of the skin.

- Increased problems healing due to decreased oxygen supply to the tissue.

- The skin will stretch and cause folds in the skin. It can increase the risk of bacterial or fungal infections underneath the skin folds.

The increased swelling and weight of the limb can create problems in gait, balance and muscle strength, - Decreased ROM of joints and decreased sensation.

- If primary lymphedema is at birth then it could affect internal organs, including genitals and intestines.

- If lymphedema is in the neck, jaw, or shoulders it could involve problems with speech, respiratory function, and swallowing.[8]

Treatment/Management[edit | edit source]

- Lymphedema is a progressive disease, and early diagnosis and treatment are paramount.

- Critical to diagnose and treat both mild and early onset cases to halt the progression of this lifelong and often debilitating condition.

- For patients to improve their knowledge base and learn helpful evidence-based management and coping strategies, patients must be referred to a specialist holding certification in lymphedema treatment and management eg.physician, an occupational therapist, or physical therapist.

Therapy

- Decongestive lymphedema therapy (DLT): Is the primary treatment for moderate-to-severe lymphedema and mobilizes lymph and dissipate fibrosclerotic tissue. [15]

- Manual lymph drainage (MLD): Light lymph massage designed to increase lymph flow

- Compression: Helps with drainage but can increase the risk of infection

- Skincare: Fastidious skin care is essential to prevent secondary skin infections

- Exercise: Light exercise promotes lymph drainage and protein absorption via muscle contraction.

Drug therapy: Adjunctive only for pain control or secondary infection

Surgery

- Debulking is often ineffective

Microsurgical techniques

- Vascularized Lymph Node Transfer (VLNT)

- Lymphaticovenous Anastomoses (LVA): VLNT and LVA are microsurgical procedures that can improve the patient's physiologic drainage of the lymphatic fluid and eliminate the need for compression garments in some patient. These procedures have better results when performed when a patient's lymphatic system has less damage.

- Suction-Assisted Protein Lipectomy (SAPL): Is more effective in later stages of lymphedema and allow removal of lymphatic solids and fatty deposits that are poor candidates for conservative lymphedema therapy, or VLNT or LVA surgeries[1]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

If treatment for cancer is necessary that should be completed first.[8] Practice pattern H in the Guide to Physical Therapy can help guide your interventions with lymphedema and the complications.[14] Physiotherapy can play a major role in the management of Lymphoedema, for a more indepth guide to physical therapy interventions visit here.

Interventions include:

- Manual lymph drainage (to help improve the flow of lymph from the affected arm or leg from proximal to distal).

- Short/low stretch Compression garment wear following lymphatic drainage.

- Skin Hygiene and care (such as cleaning the skin of the arm or leg daily and moisten with lotion).

- Exercise to improve cardiovascular health and help decrease swelling in some cases.

- Patient education (instruction in proper diet to decrease fluid retention and how to avoid injury and infection, anatomy, and self bandaging).

- Compression pumps

- Psychological and emotional support

- Garment fitting.[15][8][16]

Complex Decongestive Therapy:

- Phase 1:

- Skin care

- Light manual massage (manual lymph drainage)

- ROM

- Compression (multi-layered bandage wrapping, highest level tolerated 20-60 mm Hg)

- Phase 2:

- Compression by low-stretch elastic stocking or sleeve

- Skin care

- Exercise

- Light massage as needed

Contraindications for compression includes arterial disease, painful postphlebitic syndrome, and occult visceral neoplasia.[16]

Complete Decongestive Therapy ( 109 seconds)

Manual Lymphatic Drainage 3 minutes 51 seconds

Self care - Lympathedema (3 minutes 20 seconds)

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Lipedema

- Cellulitis

- Dermatologic Manifestations of Cardiac Disease

- Dermatologic Manifestations of Renal Disease

- Erysipelas

- Filariasis

- Lymphangioma

- Thrombophlebitis

- Venous Insufficiency[17]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Courneya K, Mackey J, Bell G.Randomized Controlled Trial of Exercise Training in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Survivors: Cardiopulmonary and Quality of Life Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol 21, Issue 9 (May), 2003: 1660-1668. http://171.66.121.246/content/21/9/1660.full Accessed on 4/5/2011.

Badger C, Peacock J, Mortimer P. A Randomized, Controlled, Parallel-Group Clinical Trial Comparing Multilayer Bandaging Followed by Hosiery versus Hosiery Alone in the Treatment of Patients with Lymphedema of the Limb. Cancer 2000;88:2832–7.© 2000 American Cancer Society.https://www.cebp.nl/media/m1159.pdf Accessed on 4/5/2011.

McNeely M, Magee D, Lees A, Bagnall K. The Addition of Manual Lymph Drainage to Compression Therapy For Breast Cancer Related Lymphedema: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Volume 86, Number 2, 95-106. http://resources.metapress.com/pdf-preview.axd?code=pm25575l0765836l&size=largest Accessed on 4/5/2011.

Resources[edit | edit source]

National Cancer Institute http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/lymphedema/Patient/Page2#Section_69

Northwest Medical Center http://northwestmed.com/our-services/lymphedema-management.dot

http://www.vascularweb.org/vascularhealth/Pages/lymphedema.aspx

http://www.medicinenet.com/breast_cancer_and_lymphedema/louisville-ky_city.htm

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Sleigh BC, Manna B. Lymphedema. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Dec 5. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537239/ (last accessed 28.7.2020)

- ↑ MacMillan Cancer Support. Specialist lymphoedema services: An evidence review. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Documents/AboutUs/Commissioners/LymphoedemaServicesAnEvidenceReview.pdf (accessed 26 January 2016).

- ↑ Cancer Research UK. Symptoms of lymphoedema. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/coping-with-cancer/coping-physically/lymphoedema/lymphoedema-symptoms (accessed 1 April 2014).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 McCallin M, Johnston J, Bassett S. How effective are physiotherapy techniques to treat established secondary lymphoedema following surgery for cancer? A critical analysis of literature. NZ Journal of Physiotherapy 2005;33:101-112. http://physiotherapy.org.nz/assets/Professional-dev/Journal/2005-November/Nov05roberts2.pdf (accessed January 10 2016).

- ↑ Lyons OTA, Modarai B. Lymphoedema. Surgery (Oxford). 2013;3:218-223. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0263931913000355 (accessed 12 January 2016).

- ↑ The Lymphoedema Support Network. How to recognise lymphoedema. http://www.lymphoedema.org/Menu4/1How%20to%20recognise%20lymphoedema.asp (accessed 12 January 2016).

- ↑ Mayo Clinic. Lymphedema. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/lymphedema/DS00609/DSECTION=symptoms (accessed 5 April 2011)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Goodman C, Fuller K. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier: 2009.

- ↑ National Cancer Institute: U.S National Institutes of Health. Lymphedema PDQ. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/lymphedema/Patient/page1. (acceessed 5 April 2011)

- ↑ 5. The Merck Manuals: The Merck Manual for Healthcare Professionals. Lymphedema. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec07/ch081/ch081h.html#sec07-ch081-ch081h-1866. (accessed 5 April 2011)

- ↑ Harmer V. Breast cancer-related lymphoedema: risk factors and treatment. Br J Community Nurs. 2009;18:166-172. http://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/10.12968/bjon.2009.18.3.39045?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed (accessed 10 October 2015).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ridner SH. The Psycho-Social impact of Lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol 2009;7:109-112. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19534633 (accessed 12 January 2016).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Greene AK, Epidemiology and Morbidity of Lymphedema. In: Greene AK, Slavin SA, Brorson H editors. Lymphedema: Presentation, Diagnosis and Treatment. Switzerland: Springer, 2015. p33-44.

- ↑ American Physical Therapy Association.Guide to Physical Therapist Practice.2nd ed. Phys Ther 2001. Revised 2003.569-585.

- ↑ American Physical Therapy Association. Lymphedema: How Physical Therapist Can Help. http://www.oncologypt.org/mbrs/factsheets/LymphedemaFactSheetFinal.pdf (accessed 5 April 2011).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 International Society of Lymphology. Diagnosis and Treatment of Periphreal Lyphology.Lymphology 42 (2009) 51-60. http://www.u.arizona.edu/~witte/ISL.htmDocument. (accessed on 5 April 2011).

- ↑ Medscape reference. Dermatological Manifestations of Lymphedema Differential Diagnosis. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1087313-differential. (accessed 5 April 2011)