Deep Vein Thrombosis: Difference between revisions

Karen Wilson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

(adding a video) |

||

| (40 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User:Jennifer Self|Jennifer Self]] | '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Jennifer Self|Jennifer Self]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div>[[Image: | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | |||

[[Image:DVT.jpg|thumb|150px|DVT: R leg with swelling and redness]] | |||

A deep-vein [[thrombosis]] (DVT) is a blood clot that forms within the deep [[Cardiovascular System|veins]], usually of the leg, but can occur in the veins of the arms and the mesenteric and cerebral veins. It is a common disorder and belongs to the venous thromboembolism disorders. DVTs represent the third most common cause of death from [[Cardiovascular Disease|cardiovascular disease]] after [[Acute Coronary Syndrome|heart attacks]] and [[stroke]], and account for most cases of [[Pulmonary Embolism|pulmonary embolism.]] Only through early diagnosis and treatment can the morbidity be reduced<ref name=":1">Kesieme E, Kesieme C, Jebbin N, Irekpita E, Dongo A. Deep vein thrombosis: a clinical review. J Blood Med 2011; 2:59–69.</ref>.<ref name=":9">Waheed SM, Kudaravalli P, Hotwagner DT. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507708/ Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)]. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Aug 10. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507708/ (last accessed 25.10.2020)</ref> For those who do develop a DVT and survive, '''post-thrombotic phlebitis''' is a lifelong sequela, which has no ideal treatment<ref name=":9" />. | |||

== | == Epidemiology == | ||

* 1.6 new cases per 1000 per year | |||

* 2.5-5% of the population is affected | |||

* >50% have long terms symptoms of post-thrombotic syndrome | |||

* 6% of DVT patients report eventual venous ulcers (0.1% general population)<ref name=":0">Radiopedia DVT Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/deep-vein-thrombosis (accessed 19.7.2022)</ref> | |||

== | == Pathology == | ||

The majority of lower extremity DVTs develop in the veins of the calf, being the peroneal veins, posterior tibial veins and the veins of the [[gastrocnemius]] and [[soleus]] muscles<ref name=":0" />. | |||

The following video provides a visual representation of DVT pathology: | The following video provides a visual representation of DVT pathology: | ||

| Line 20: | Line 22: | ||

== Risk Factors == | == Risk Factors == | ||

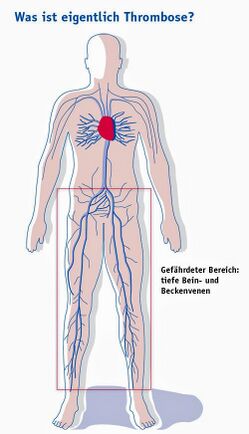

[[File:DVT sites.jpeg|thumb|434x434px|Mapping the at-risk area for deep vein thrombosis ]] | |||

Following are the risk factors and are considered as causes of deep venous thrombosis: | |||

*Reduced [[Blood Physiology|blood]] flow: Immobility (bed rest, general [[Surgery and General Anaesthetic|anesthesia]], operations or surgery<ref>Solis G, Saxby T. Incidence of DVT following surgery of the foot and ankle. Foot & ankle international. 2002 May;23(5):411-4.</ref>, long flights) | |||

* Mechanical compression or functional impairment which reduces flow in the veins (eg [[Oncology|neoplasm]], pregnancy, [[Varicose Veins|varicose veins]]) | |||

* Mechanical injury to the vein eg Trauma, surgery, peripherally inserted venous catheters, previous DVT, intravenous drug abuse. | |||

| | * Increased blood viscosity eg thrombocytosis, [[dehydration]] | ||

* Anatomic variations in venous anatomy can contribute to thrombosis. | |||

* | Increased Risk of Coagulation | ||

* | * Genetic deficiencies: Anticoagulation proteins C and S, antithrombin III deficiency, factor V Leiden mutation | ||

* Acquired: eg Cancer, [[sepsis]], [[Myocardial Infarction|myocardial infarction]], [[Heart Failure|heart failure]], vasculitis, [[Systemic Lupus Erythematosus|systemic lupus erythematosus]], [[Irritable Bowel Syndrome|inflammatory bowel disease]], [[Chronic Kidney Disease|nephrotic]] syndrome, burns, oral estrogens, [[Smoking Cessation and Brief Intervention|smoking]], [[Blood Pressure|hypertension]], [[diabetes]] | |||

* | Constitutional Factors | ||

* | * [[Obesity]], pregnancy, [[Older People - An Introduction|Increasing age]], surgery, and cancer. | ||

== Clinical Presentation == | |||

[[File:Varices de la safena magna.jpg|alt=|thumb|Varicose veins of the great saphenous vein]]History | |||

# Pain (50% of patients) | |||

# Redness | |||

# Swelling (70% of patients) | |||

Physical Examination | |||

# Limb [[Oedema Assessment|edema]] may be unilateral or bilateral if the thrombus is extending to pelvic veins | |||

* | # Red and hot [[skin]], with dilated veins | ||

# Tenderness<ref name=":9" /> | |||

| | |||

[ | |||

== Clinical Prediction Rule (CPR): Well's Criteria == | |||

== Clinical Prediction Rule ( | |||

Well's Criteria is the most commonly used tool to screen for DVT risk:<ref name=":1" /> | Well's Criteria is the most commonly used tool to screen for DVT risk:<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| Line 75: | Line 57: | ||

| +1 | | +1 | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Recently | |Recently bed ridden for > 3 days or major surgery within 4 weeks<ref>Song K, Yao Y, Rong Z, Shen Y, Zheng M, Jiang Q. The preoperative incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and its correlation with postoperative DVT in patients undergoing elective surgery for femoral neck fractures. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2016 Oct;136:1459-64.</ref> | ||

| +1 | | +1 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 96: | Line 78: | ||

| -2 | | -2 | ||

|} | |} | ||

In the original scale | '''In the original scale:''' | ||

the total score for all items is tallied and the probability of the patient having a DVT is as follows: 0= low probability, 1-2 points= moderate probability ,and ≥ 3 points= high probability.<ref>Wells PS, Hirsh J, Anderson DR, Lensing AW, Foster G, Kearon C, Weitz J, D'Ovidio R, Cogo A, Prandoni P. Accuracy of clinical assessment of deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet 1995; 345(8961):1326-1330</ref> An updated version simplifies the scoring process into two categories: < 2 points= DVT unlikely, ≥ 2 points= DVT likely.<ref>Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Forgie M, Kearon C, Dreyer J, Kovacs G, Mitchell M, Lewandowski B, Kovacs MJ. Evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of suspected deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:1227–1235</ref> | |||

== | '''Well's Criteria'''<ref>Modi S, Deisler R, Gozel K, Reicks P, Irwin E, Brunsvold M, Banton K, Beilman GJ. Wells criteria for DVT is a reliable clinical tool to assess the risk of deep venous thrombosis in trauma patients. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2016 Dec;11:1-6.</ref> is a valid tool for assessing DVT risk in outpatient<ref>Wells PS, Anderson DR, Bormanis J, Guy F, Mitchell M, Gray L, Clement C, Robinson KS, Lewandowski B. Value of assessment of pretest probability of deep-vein thrombosis in clinical management. Lancet 1997; 350(9094):1795-1798</ref><ref name=":5">Geersing GJ, Zuithoff NPA, Kearon C, Anderson DR, Cate-Hoek T, Elf JL, Bates SM, Hoes AW, Kraaijenhagen RA, Oudega R, Schutgens RE, Stevens SM, Woller SC, Wells PS, Moons KG. Exclusion of deep vein thrombosis using the Wells rule in clinically important subgroups: individual patient data meta-analysis. BMJ 2014; 348:g1340</ref> and trauma<ref>Modi S, Deisler R, Gozel K, Reicks P, Irwin E, Brunsvold M, Banton K, Beilman GJ. Wells criteria for DVT is a reliable clinical tool to assess the risk of deep venous thrombosis in trauma patients. World J Emerg Surg. 2016; 11: 24</ref> patients. It is '''less useful''' for stratifying risk in cancer patients<ref name=":5" /> and hospitalized patients as a whole.<ref>Silveira PC, Ip IK, Goldhaber SZ, Piazza G, Benson CB, Khorasani R. Performance of Wells Score for Deep Vein Thrombosis in the Inpatient Setting. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175(7):1112-7</ref> It cannot be used to screen for UE DVT.<ref name=":2">Heil J, Miesbach W, Vogl T, Bechstein WO, Reinisch A. Deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity: A systematic review. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017; 114(14): 244–249</ref> | ||

== Clinical Tests == | |||

== | |||

The clinical diagnosis of DVT is unreliable. However, in combination with valid screening tools, clinical examination can justify the need for diagnostic testing<ref>Scarvelis D, Wells PS. Diagnosis and treatment of deep-vein thrombosis. Cmaj. 2006 Oct 24;175(9):1087-92.</ref>. | |||

* Focus on identifying the signs and symptoms described in the "Clinical Presentation" section of this article. | |||

[[Homan's Sign Test|Homan's Sign]] | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | |||

[[Image:Venography.jpg|thumb|200px|Venography]] | [[Image:Venography.jpg|thumb|200px|Venography]] | ||

As per the NICE guidelines following investigations are done: | |||

* D-dimers (very sensitive but not very specific) | |||

* Coagulation profile | |||

* Proximal leg vein ultrasound, which when positive, indicates that the patient should be treated as having a DVT<ref name=":9" /> | |||

D-Dimer Testing | |||

* D-dimer testing is a simple blood test of fibrin degradation. D-dimer levels are increased by any condition that produces fibrin, one of the primary components of deep vein thrombi. The negative likelihood ratio is higher than 99%. According to Wells and colleagues,<ref name="Riddle">Riddle DL, Wells PS. Diagnosis of Lower-Extremity Deep Vein Thrombosis in Outpatients. Physical Therapy. 84 (8); 729-735.</ref> the test is best used to rule out DVT in outpatients with a low probability of proximal DVT.<br> | |||

== Management / Interventions == | == Management / Interventions == | ||

'''Primary Prevention''' | |||

A combination of '''mechanical''' and '''pharmacological''' measures can be used to prevent DVT<ref>Morillo R, Jiménez D, Aibar MÁ, Mastroiacovo D, Wells PS, Sampériz Á, De Sousa MS, Muriel A, Yusen RD, Monreal M, Decousus H. DVT management and outcome trends, 2001 to 2014. Chest. 2016 Aug 1;150(2):374-83.</ref>. Mechanical prophylaxis involves the use of graduated compression stockings (GCS), intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) and venous foot pumps to improve blood flow in the deep veins of the leg. Common agents for pharmacological prophylaxis include Warfarin, subcutaneous unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH).<ref name=":3">Joffe H, Kucher N, Tapson V, Goldhaber S. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis: a prospective registry of 593 patients. Circulation 2004; 110: 1605-1611</ref> DVT prevention is most effective when both methods are used simultaneously.<ref name=":1" /> In medical and surgical patients ambulation and exercises involving ankle dorsiflexion are encouraged to further minimize venous stasis.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

A combination of mechanical and pharmacological measures can be used to prevent DVT. Mechanical prophylaxis involves the use of graduated compression stockings (GCS), intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) and venous foot pumps to improve blood flow in the deep veins of the leg. Common agents for pharmacological prophylaxis include Warfarin, subcutaneous unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH).<ref name=":3" /> DVT prevention is most effective when both methods are used simultaneously.<ref name=":1" /> In medical and surgical patients ambulation and exercises involving ankle dorsiflexion are encouraged to further minimize venous stasis.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

'''Medical Management''' | |||

Treatment of DVT aims to prevent pulmonary embolism, reduce morbidity, and prevent or minimize the risk of developing post-thrombotic syndrome. | |||

The cornerstone of treatment is anticoagulation. NICE guidelines only recommend treating proximal DVT (not distal) and those with pulmonary emboli. In each patient, the risks of anticoagulation need to be weighed against the benefits | |||

'''Secondary Prevention'''[[File:Compression stockings.jpg|thumb|271x271px|Compression stockings.]]Early Mobilization | |||

* In conjunction with anti-coagulation, bed rest is commonly prescribed in the immediate days following the diagnosis of LE DVT. This practice is applied with the intent of preventing clot dislodgement and the incidence of PE. The theoretical basis behind this protocol has not been supported by the literature.<ref>Aissaoui N, Martins E, Mouly S, Wever S, Meune C. A meta-analysis of bed rest versus early ambulation in the management of pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, or both. Int J Cardiol 2009;137:37–41</ref><ref name=":7">Kahn SR, Shrier I, Kearon C. Physical activity in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Thromb Res 2008; 122:763–773</ref> According to a systematic review,<ref name=":7" /> early ambulation is associated with fewer incidences of new PE and decreased mortality. As such, early mobilization is instrumental for the prevention of DVT sequelae (see the next section on "Implications for Physical Therapy Practice" for guidelines on safe patient mobilization following known DVT). | |||

Graduated Compression Stockings | |||

* To prevent DVT recurrence, the application of graduated compression stockings is recommended "beginning within 1 month of diagnosis of proximal DVT and continuing for a minimum of 1 year after diagnosis".<ref name="Snow">Snow V, Qaseem A, Barry P, et al. (2007). "Management of venous thromboembolism: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (3): 204–10.</ref> | |||

[[File:Compression stockings.jpg|thumb|271x271px]] | |||

In conjunction with anti-coagulation, bed rest is commonly prescribed in the immediate days following the diagnosis of LE DVT. This practice is applied with the intent of preventing clot dislodgement and the incidence of PE. The theoretical basis behind this protocol has not been supported by the literature.<ref>Aissaoui N, Martins E, Mouly S, Wever S, Meune C. A meta-analysis of bed rest versus early ambulation in the management of pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, or both. Int J Cardiol 2009;137:37–41</ref><ref name=":7">Kahn SR, Shrier I, Kearon C. Physical activity in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Thromb Res 2008; 122:763–773</ref> | |||

== Implications for Physical Therapy Practice == | == Implications for Physical Therapy Practice == | ||

Physical therapists work with patients at risk for and with diagnosed DVT across the continuum of care. For this reason, the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) has developed clinical practice guidelines (CPG)<ref name=":8">Hillegass E, Puthoff M, Frese EM, Thigpen M, Sobush DC, Auten B. Role of Physical Therapists in the Management of Individuals at Risk for or Diagnosed With Venous Thromboembolism: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. Phys Ther 2016; 96(2):143-66</ref> to facilitate | Physical therapists work with patients at risk for and with diagnosed DVT across the continuum of care. For this reason, the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) has developed clinical practice guidelines (CPG)<ref name=":8">Hillegass E, Puthoff M, Frese EM, Thigpen M, Sobush DC, Auten B. Role of Physical Therapists in the Management of Individuals at Risk for or Diagnosed With Venous Thromboembolism: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. Phys Ther 2016; 96(2):143-66</ref> <ref>Hillegass E, Puthoff M, Frese EM, Thigpen M, Sobush DC, Auten B, Guideline Development Group. Role of physical therapists in the management of individuals at risk for or diagnosed with venous thromboembolism: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Physical therapy. 2016 Feb 1;96(2):143-66.</ref>to facilitate decision making in the prevention and management of LE DVT in adults. The following table outlines the 5 responsibilities of physical therapists (PTs) with actionable recommendations: | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

!PT Responsibilities | !PT Responsibilities | ||

| Line 159: | Line 125: | ||

* Recommend/use mechanical compression for individuals at moderate or high risk for DVT | * Recommend/use mechanical compression for individuals at moderate or high risk for DVT | ||

* Consult with the physician about medication for individuals at moderate or high risk for DVT | * Consult with the physician about medication for individuals at moderate or high risk for DVT | ||

* Provide education on DVT prevention (leg exercises, ambulation, hydration | * Provide education on DVT prevention (leg exercises, ambulation, hydration, etc) | ||

* Provide education on the risk factors, signs and symptoms and consequences of DVT | * Provide education on the risk factors, signs and symptoms, and consequences of DVT | ||

|- | |- | ||

|(2) Screening for LE DVT | |(2) Screening for LE DVT | ||

| | | | ||

* Screen for DVT risk using Well's Criteria or the preferred risk assessment model of the treating institution. | * Screen for DVT risk using Well's Criteria or the preferred risk assessment model of the treating institution. | ||

* Communicate screening results and relevant clinical signs and symptoms to the medical team | * Communicate screening results and relevant clinical signs and symptoms to the medical team. | ||

* Provide education on the importance of seeking medical attention for suspected DVT | * Provide education on the importance of seeking medical attention for suspected DVT. | ||

|- | |- | ||

|(3) Making prudent decisions regarding safe mobility in conjunction with the health care team | |(3) Making prudent decisions regarding safe mobility in conjunction with the health care team | ||

| | | | ||

* Advocate for diagnostic testing before mobilizing patients with suspected DVT | * Advocate for diagnostic testing and wait the results before mobilizing patients with suspected DVT | ||

* Screen for fall-risk when a patient is on anticoagulation therapy | * Screen for fall-risk when a patient is on anticoagulation therapy | ||

* Engage patients with known DVT in early mobilization. Recommendations for when | * Engage patients with known DVT in early mobilization. Recommendations for how and when it is safe to mobilize a patient with known DVT depends on patient fall-risk the medical treatment being used: | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

!Medical Treatment | !Medical Treatment | ||

| Line 190: | Line 156: | ||

|Out of bed ordered for a patient with no anticoagulation therapy or IVC filter | |Out of bed ordered for a patient with no anticoagulation therapy or IVC filter | ||

| | | | ||

# Consult with the medical team regarding mobility vs | # Consult with the medical team regarding mobility vs continued bed rest. | ||

|} | |} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 201: | Line 167: | ||

|(5) Patient education & shared decision making | |(5) Patient education & shared decision making | ||

| | | | ||

* Patient education should | * Patient education should be given throughout the DVT prevention and management process. | ||

* Patients should have the autonomy to | * Patients should have the autonomy to decide if they want to engage in recommended prevention and treatment measures. | ||

|} | |} | ||

{{#ev:youtube|Ali7rFYfJuY}} | |||

Resources | |||

* [https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/96/2/143/2686356 Role of Physical Therapists in the Management of Individuals at Risk for or Diagnosed With Venous Thromboembolism: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline.]<div class="coursebox"></div> | |||

* [https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/96/2/143/2686356 Role of Physical Therapists in the Management of Individuals at Risk for or Diagnosed With Venous Thromboembolism: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline | |||

<div class="coursebox"> | |||

</div> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

| Line 267: | Line 178: | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

[[Category:EBP]] [[Category: | [[Category:EBP]] | ||

[[Category:Older_People/Geriatrics]] | |||

[[Category:EIM_Residency_Project]] | |||

[[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | |||

[[Category:Primary Contact]] | |||

[[Category:Acute Care]] | |||

[[Category:Medical]] | |||

[[Category:Cardiopulmonary]] | |||

[[Category:Cardiovascular Disease - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Acute Respiratory Disorders - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Older People/Geriatrics - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Non Communicable Diseases]] | |||

Latest revision as of 15:05, 2 February 2023

Original Editor - Jennifer Self

Top Contributors - Admin, Karen Wilson, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Scott Buxton, Jennifer Self, Shaimaa Eldib, Lucinda hampton, Ayesha Arabi, WikiSysop, Adam Vallely Farrell and Claire Knott

Introduction[edit | edit source]

A deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) is a blood clot that forms within the deep veins, usually of the leg, but can occur in the veins of the arms and the mesenteric and cerebral veins. It is a common disorder and belongs to the venous thromboembolism disorders. DVTs represent the third most common cause of death from cardiovascular disease after heart attacks and stroke, and account for most cases of pulmonary embolism. Only through early diagnosis and treatment can the morbidity be reduced[1].[2] For those who do develop a DVT and survive, post-thrombotic phlebitis is a lifelong sequela, which has no ideal treatment[2].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- 1.6 new cases per 1000 per year

- 2.5-5% of the population is affected

- >50% have long terms symptoms of post-thrombotic syndrome

- 6% of DVT patients report eventual venous ulcers (0.1% general population)[3]

Pathology[edit | edit source]

The majority of lower extremity DVTs develop in the veins of the calf, being the peroneal veins, posterior tibial veins and the veins of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles[3].

The following video provides a visual representation of DVT pathology:

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Following are the risk factors and are considered as causes of deep venous thrombosis:

- Reduced blood flow: Immobility (bed rest, general anesthesia, operations or surgery[4], long flights)

- Mechanical compression or functional impairment which reduces flow in the veins (eg neoplasm, pregnancy, varicose veins)

- Mechanical injury to the vein eg Trauma, surgery, peripherally inserted venous catheters, previous DVT, intravenous drug abuse.

- Increased blood viscosity eg thrombocytosis, dehydration

- Anatomic variations in venous anatomy can contribute to thrombosis.

Increased Risk of Coagulation

- Genetic deficiencies: Anticoagulation proteins C and S, antithrombin III deficiency, factor V Leiden mutation

- Acquired: eg Cancer, sepsis, myocardial infarction, heart failure, vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, nephrotic syndrome, burns, oral estrogens, smoking, hypertension, diabetes

Constitutional Factors

- Obesity, pregnancy, Increasing age, surgery, and cancer.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

History

- Pain (50% of patients)

- Redness

- Swelling (70% of patients)

Physical Examination

- Limb edema may be unilateral or bilateral if the thrombus is extending to pelvic veins

- Red and hot skin, with dilated veins

- Tenderness[2]

Clinical Prediction Rule (CPR): Well's Criteria[edit | edit source]

Well's Criteria is the most commonly used tool to screen for DVT risk:[1]

| Clinical Variable | Score |

|---|---|

| Active cancer (treatment ongoing or within previous 6 months, or palliative) | +1 |

| Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilization of the lower extremities | +1 |

| Recently bed ridden for > 3 days or major surgery within 4 weeks[5] | +1 |

| Localized tenderness along the distribution of the deep venous system (Tenderness along the deep venous system is assessed by firm palpation in the center of the posterior calf, the popliteal space, and along the area of the femoral vein in the anterior thigh and groin) | +1 |

| Entire lower extremity swelling | +1 |

| Calf swelling > 3 cm when compared with the asymptomatic lower extremity (measured 10cm below the tibial tuberosity) | +1 |

| Pitting edema confined to the symptomatic lower extremity | +1 |

| Collateral superficial veins (non-varicose) | +1 |

| Alternative diagnosis as likely or greater than that of proximal DVT (More common alternative diagnoses include cellulitis, calf strain, Baker Cyst, or postoperative swelling) | -2 |

In the original scale:

the total score for all items is tallied and the probability of the patient having a DVT is as follows: 0= low probability, 1-2 points= moderate probability ,and ≥ 3 points= high probability.[6] An updated version simplifies the scoring process into two categories: < 2 points= DVT unlikely, ≥ 2 points= DVT likely.[7]

Well's Criteria[8] is a valid tool for assessing DVT risk in outpatient[9][10] and trauma[11] patients. It is less useful for stratifying risk in cancer patients[10] and hospitalized patients as a whole.[12] It cannot be used to screen for UE DVT.[13]

Clinical Tests[edit | edit source]

The clinical diagnosis of DVT is unreliable. However, in combination with valid screening tools, clinical examination can justify the need for diagnostic testing[14].

- Focus on identifying the signs and symptoms described in the "Clinical Presentation" section of this article.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

As per the NICE guidelines following investigations are done:

- D-dimers (very sensitive but not very specific)

- Coagulation profile

- Proximal leg vein ultrasound, which when positive, indicates that the patient should be treated as having a DVT[2]

D-Dimer Testing

- D-dimer testing is a simple blood test of fibrin degradation. D-dimer levels are increased by any condition that produces fibrin, one of the primary components of deep vein thrombi. The negative likelihood ratio is higher than 99%. According to Wells and colleagues,[15] the test is best used to rule out DVT in outpatients with a low probability of proximal DVT.

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Primary Prevention

A combination of mechanical and pharmacological measures can be used to prevent DVT[16]. Mechanical prophylaxis involves the use of graduated compression stockings (GCS), intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) and venous foot pumps to improve blood flow in the deep veins of the leg. Common agents for pharmacological prophylaxis include Warfarin, subcutaneous unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH).[17] DVT prevention is most effective when both methods are used simultaneously.[1] In medical and surgical patients ambulation and exercises involving ankle dorsiflexion are encouraged to further minimize venous stasis.[1]

Medical Management

Treatment of DVT aims to prevent pulmonary embolism, reduce morbidity, and prevent or minimize the risk of developing post-thrombotic syndrome.

The cornerstone of treatment is anticoagulation. NICE guidelines only recommend treating proximal DVT (not distal) and those with pulmonary emboli. In each patient, the risks of anticoagulation need to be weighed against the benefits

Secondary Prevention

Early Mobilization

- In conjunction with anti-coagulation, bed rest is commonly prescribed in the immediate days following the diagnosis of LE DVT. This practice is applied with the intent of preventing clot dislodgement and the incidence of PE. The theoretical basis behind this protocol has not been supported by the literature.[18][19] According to a systematic review,[19] early ambulation is associated with fewer incidences of new PE and decreased mortality. As such, early mobilization is instrumental for the prevention of DVT sequelae (see the next section on "Implications for Physical Therapy Practice" for guidelines on safe patient mobilization following known DVT).

Graduated Compression Stockings

- To prevent DVT recurrence, the application of graduated compression stockings is recommended "beginning within 1 month of diagnosis of proximal DVT and continuing for a minimum of 1 year after diagnosis".[20]

Implications for Physical Therapy Practice[edit | edit source]

Physical therapists work with patients at risk for and with diagnosed DVT across the continuum of care. For this reason, the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) has developed clinical practice guidelines (CPG)[21] [22]to facilitate decision making in the prevention and management of LE DVT in adults. The following table outlines the 5 responsibilities of physical therapists (PTs) with actionable recommendations:

| PT Responsibilities | Actionable Recommendations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Prevention of VTE |

| ||||||||

| (2) Screening for LE DVT |

| ||||||||

| (3) Making prudent decisions regarding safe mobility in conjunction with the health care team |

| ||||||||

| (4) Prevention of long-term consequences of LE DVT |

| ||||||||

| (5) Patient education & shared decision making |

|

Resources

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kesieme E, Kesieme C, Jebbin N, Irekpita E, Dongo A. Deep vein thrombosis: a clinical review. J Blood Med 2011; 2:59–69.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Waheed SM, Kudaravalli P, Hotwagner DT. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT). StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Aug 10. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507708/ (last accessed 25.10.2020)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Radiopedia DVT Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/deep-vein-thrombosis (accessed 19.7.2022)

- ↑ Solis G, Saxby T. Incidence of DVT following surgery of the foot and ankle. Foot & ankle international. 2002 May;23(5):411-4.

- ↑ Song K, Yao Y, Rong Z, Shen Y, Zheng M, Jiang Q. The preoperative incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and its correlation with postoperative DVT in patients undergoing elective surgery for femoral neck fractures. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2016 Oct;136:1459-64.

- ↑ Wells PS, Hirsh J, Anderson DR, Lensing AW, Foster G, Kearon C, Weitz J, D'Ovidio R, Cogo A, Prandoni P. Accuracy of clinical assessment of deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet 1995; 345(8961):1326-1330

- ↑ Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Forgie M, Kearon C, Dreyer J, Kovacs G, Mitchell M, Lewandowski B, Kovacs MJ. Evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of suspected deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:1227–1235

- ↑ Modi S, Deisler R, Gozel K, Reicks P, Irwin E, Brunsvold M, Banton K, Beilman GJ. Wells criteria for DVT is a reliable clinical tool to assess the risk of deep venous thrombosis in trauma patients. World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 2016 Dec;11:1-6.

- ↑ Wells PS, Anderson DR, Bormanis J, Guy F, Mitchell M, Gray L, Clement C, Robinson KS, Lewandowski B. Value of assessment of pretest probability of deep-vein thrombosis in clinical management. Lancet 1997; 350(9094):1795-1798

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Geersing GJ, Zuithoff NPA, Kearon C, Anderson DR, Cate-Hoek T, Elf JL, Bates SM, Hoes AW, Kraaijenhagen RA, Oudega R, Schutgens RE, Stevens SM, Woller SC, Wells PS, Moons KG. Exclusion of deep vein thrombosis using the Wells rule in clinically important subgroups: individual patient data meta-analysis. BMJ 2014; 348:g1340

- ↑ Modi S, Deisler R, Gozel K, Reicks P, Irwin E, Brunsvold M, Banton K, Beilman GJ. Wells criteria for DVT is a reliable clinical tool to assess the risk of deep venous thrombosis in trauma patients. World J Emerg Surg. 2016; 11: 24

- ↑ Silveira PC, Ip IK, Goldhaber SZ, Piazza G, Benson CB, Khorasani R. Performance of Wells Score for Deep Vein Thrombosis in the Inpatient Setting. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175(7):1112-7

- ↑ Heil J, Miesbach W, Vogl T, Bechstein WO, Reinisch A. Deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity: A systematic review. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017; 114(14): 244–249

- ↑ Scarvelis D, Wells PS. Diagnosis and treatment of deep-vein thrombosis. Cmaj. 2006 Oct 24;175(9):1087-92.

- ↑ Riddle DL, Wells PS. Diagnosis of Lower-Extremity Deep Vein Thrombosis in Outpatients. Physical Therapy. 84 (8); 729-735.

- ↑ Morillo R, Jiménez D, Aibar MÁ, Mastroiacovo D, Wells PS, Sampériz Á, De Sousa MS, Muriel A, Yusen RD, Monreal M, Decousus H. DVT management and outcome trends, 2001 to 2014. Chest. 2016 Aug 1;150(2):374-83.

- ↑ Joffe H, Kucher N, Tapson V, Goldhaber S. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis: a prospective registry of 593 patients. Circulation 2004; 110: 1605-1611

- ↑ Aissaoui N, Martins E, Mouly S, Wever S, Meune C. A meta-analysis of bed rest versus early ambulation in the management of pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, or both. Int J Cardiol 2009;137:37–41

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Kahn SR, Shrier I, Kearon C. Physical activity in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Thromb Res 2008; 122:763–773

- ↑ Snow V, Qaseem A, Barry P, et al. (2007). "Management of venous thromboembolism: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (3): 204–10.

- ↑ Hillegass E, Puthoff M, Frese EM, Thigpen M, Sobush DC, Auten B. Role of Physical Therapists in the Management of Individuals at Risk for or Diagnosed With Venous Thromboembolism: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. Phys Ther 2016; 96(2):143-66

- ↑ Hillegass E, Puthoff M, Frese EM, Thigpen M, Sobush DC, Auten B, Guideline Development Group. Role of physical therapists in the management of individuals at risk for or diagnosed with venous thromboembolism: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Physical therapy. 2016 Feb 1;96(2):143-66.