Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (47 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User:Pamela Gonzalez|Pamela Gonzalez]], [[User:Bahire Evelyne|Bahire Evelyne]] | '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Pamela Gonzalez|Pamela Gonzalez]], [[User:Bahire Evelyne|Bahire Evelyne]] | ||

'''Lead Editors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Lead Editors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== | == Introduction == | ||

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD), refers to idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral epiphysis seen in children. | |||

[[ | It is a diagnosis of exclusion and other causes of osteonecrosis (including [[Sickle Cell Anemia|sickle cell disease]], [[Leukemia|leukaemia]], [[Corticosteroid Medication|corticosteroid]] administration, [[Gaucher Disease|Gaucher]] disease) must be ruled out.[[File:LeggCalvePerthes.jpeg|frameless|alt=XRay - Bilateral Avascular Necrosis Femoral Head (Legg Calve Perthes Disease)|center]] | ||

'''Image 1:''' [[X-Rays|XRay]] - Bilateral [[Avascular Necrosis Femoral Head]] (Legg Calve Perthes Disease) | |||

LCPD is | == Etiology == | ||

The cause of LCPD is not known. It may be idiopathic or due to other aetiology that would disrupt [[blood]] flow to the femoral epiphysis, e.g. trauma (macro or repetitive microtrauma), coagulopathy, and steroid use. Thrombophilia is present in approximately 50% of patients, and some form of coagulopathy is present in up to 75%<ref name=":1">Mills S, Burroughs KE. [https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/24174/ Legg Calve Perthes Disease]. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jul 13.Available:https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/24174/ (accessed 15.10.2021).</ref>. | |||

== Epidemiology == | |||

LCPD disease is relatively uncommon and in Western populations has an incidence approaching 5 to 15:100,000. | |||

= | * Boys are five times more likely to be affected than girls. | ||

* Presentation is typically at a younger age than slipped upper femoral epiphysis (SUFE) with peak presentation at 5-6 years, but confidence intervals are as wide as 2-14 years.<ref name=":0">Radiopedia [https://radiopaedia.org/articles/perthes-disease Perthes Disease] Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/perthes-disease (accessed 15.10.2021).</ref> | |||

The | ==Pathology== | ||

The specific cause of osteonecrosis in LPCD disease is unclear. | |||

Osteonecrosis generally occurs secondary to the abnormal or damaged blood supply to the femoral epiphysis, leading to fragmentation, bone loss, and eventual structural collapse of the femoral head. In approximately 15% of cases, osteonecrosis occurs bilaterally<ref name=":0" />. | |||

< | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

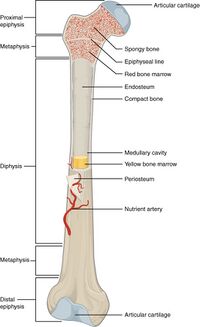

A long bone has two parts: the diaphysis and the '''epiphysis.''' The diaphysis is the tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of the bone. The hollow region in the diaphysis is called the medullary cavity, which is filled with yellow [[Bone Marrow|marrow]]. The walls of the diaphysis are composed of dense and hard compact bone.<ref name=":2">Hall JE. Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology e-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015 May 31.</ref> | |||

[[File:603 Anatomy of Long Bone.jpg|frameless|327x327px|alt=|center]] | |||

'''Image 2: Anatomy of Long Bone, note epiphysis.''' | |||

== Presentation == | |||

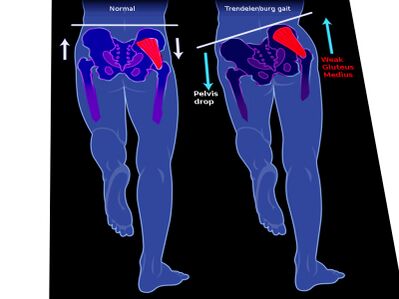

LCPD is present in children 2-13 years of age and there is a four times the greater incidence in males compared to females. The average age of occurrence is six years.<ref name="John Anthony Herring2">Herring JA, editor. Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease. 1st edition. Rosemont: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 1996 p.6-16.</ref>[[File:Trendelenburg .jpeg|right|frameless|399x399px|alt=Pelvic aligment during normal gait vs trendelenburg gait]] | |||

'''History''' | |||

* Limp of acute or insidious onset, often painless (1 to 3 months). | |||

* If pain is present, it can be localized to the hip or referred to the knee, thigh, or abdomen. | |||

* With progression, pain typically worsens with activity. | |||

* No systemic symptoms should be found. | |||

'''Image 2''': [[Trendelenburg Gait|Trendelenburg gait]] | |||

'''Physical Examination''' | |||

* Decreased internal rotation and abduction of the hip. | |||

* Pain on rotation referred to the anteromedial thigh and/or knee. | |||

* Atrophy of thighs and buttocks from pain leading to disuse. | |||

* Afebrile | |||

* Limb-length discrepancy | |||

'''Gait Evaluation''' | |||

* [[Gait: Antalgic|Antalgic gait]] (acute): Short-stance phase secondary to pain in the weight-bearing leg. | |||

* [[Trendelenburg Gait|Trendelenburg gait]] (chronic): Downward pelvic tilt away from the affected hip during the swing phase[5]. | |||

== Staging == | |||

Multiple classifications can be utilized to describe Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. The lateral pillar, or Herring, classification is widely accepted with the best interobserver agreement. It is generally determined at the beginning of the fragmentation stage, approximately 6 months after initial symptom presentation. It cannot be used accurately if the patient has not entered the fragmentation stage. | |||

# Group A: The lateral pillar is at full height with no density changes. This group has a consistently good prognosis. | |||

# Group B: The lateral pillar maintains greater than 50% height. There will be a poor outcome if the bone age is greater than 6. | |||

# Group C: Less than 50% of the lateral pillar height is maintained. All patients will experience a poor outcome radiographically. The goal is to provide prognostic information. This classification is based on the height of the lateral pillar on the AP X-ray image.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

Treatment in Perthes disease is largely related to symptom control, particularly in the early phase of the disease. As the disease progresses, fragmentation and destruction of the femoral head occur. In this situation, operative management is sometimes required to either ensure appropriate coverage of the femoral head by the acetabulum or to replace the femoral head in adult life. | |||

== Treatment == | |||

Goals of treatment include pain and symptom management, restoration of hip range of motion, and containment of the femoral head in the acetabulum.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

The younger the age at the time of presentation, the more benign disease course is expected, and also for the same age, the prognosis is better in boys than girls due to less maturity. Conservative treatment is favourable in children with a skeletal age of 6 years or less at the time of disease onset<ref name=":0" />. | |||

==== 1. Nonoperative Treatment ==== | |||

* Indicated for children with bone age less than 6 or lateral pillar A involvement. | |||

* Activity restriction and protective weight-bearing are recommended until ossification is complete. | |||

* The patient may still take part in physical therapy. | |||

* Literature does not support the use of orthotics, braces, or casts. | |||

* NSAIDs can be prescribed for comfort. | |||

* Referral to an experienced pediatric orthopedist is recommended. | |||

==== 2. Operative Treatment. ==== | |||

'''Femoral or Pelvic Osteotomy'''<ref name=":1" /> | |||

* Indicated in children over 8 years old. | |||

* Outcomes are better in lateral pillar B and B/C with surgery compared to A and C | |||

* Research suggests that surgery should be early before deformity of the femoral head develops. | |||

'''Valgus or Shelf Osteotomies'''<ref name=":1" /> | |||

* Indicated in children who have hinge abduction. | |||

* Results in improvements to the abductor mechanism | |||

'''Hip Arthroscopy'''<ref name=":1" /> | |||

* Is becoming more common as a modality for mechanical symptoms and/or femoroacetabular impingement | |||

'''Hip Arthrodiastasis'''<ref name=":1" /> | |||

< | * Considered a more controversial option.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

In later life, hip replacements may be necessary.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

==Differential Diagnosis== | |||

Listed are some other disorders that should be included in the differential diagnosis for LCPD: All diseases which induce necrosis of the head or those resembling them are questioned in a differential diagnosis<ref name=":3">Manig, M. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD). Principles of diagnosis and treatment. Orthopäde 2013;42(10):891-90.</ref>: | |||

* [[Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis|Slipped superior femoral epiphysis]] | |||

* [[Osteomyelitis]] | |||

* Secondary causes of osteonecrosis | |||

* Dysplasia epiphyseal capitis femoris (Meyer dysplasia) | |||

* Tumours | |||

* [[Haemophilia]] | |||

*[[Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis]] : a chronic inflammatory disorder that occurs before the age of 16 and can occur in all races. <ref name=":12">Hunter JB. [https://www.orthopaedicsandtraumajournal.co.uk/article/S0268-0890(04)00065-9/abstract (iv) Legg Calvé Perthes’ disease.] Curr Orthopaed 2004;18(4):273-83.</ref> | |||

==Diagnostic Procedures== | |||

An MRI is usually obtained to confirm the diagnosis; however, x-rays can also be of use to determine femoral head positioning. | |||

Since LCPD has a variable end result, an imaging modality that can predict the outcome at the initial stage of the disease before significant deformity has occurred is ideal. | |||

The extent of femoral head involvement depicted by non-contrast and contrast MRI showed no correlation at the initial stage of LCPD, indicating that they are assessing two different components of the disease process. In the initial stage of LCPD, contrast MRI provided a clearer depiction of the area of involvement. <ref>Kim, HK, Kaste, S, Dempsey M, Wilkes D. A comparison of non-contrast and contrast-enhanced MRI in the initial stage of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Pediatr Radiol 2013;43:1166. </ref> | |||

To quantify femoral head deformity in patients with LCPD novel three dimensional (3D) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reconstruction and volume-based analysis can be used. The 3D MRI volume ratio method allows accurate quantification and demonstrated small changes (less than 10 per cent) of the femoral head deformity in LCPD. This method may serve as a useful tool to evaluate the effects of treatment on femoral head shape.<ref>Standefer KD, Dempsey M, Jo C, Kim HKW. 3D MRI quantification of femoral head deformity in Legg‐Calvé‐Perthes disease." J Orthop Res 2016;35(9):2051-2058.</ref> | |||

==Outcome Measures== | |||

*[[Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)|Lower Extremity Functional Scale]]. | |||

*[[Harris Hip Score]]<ref>Kirmit L, Karatosun V, Unver B, Bakirhan S, Sen A, Gocen Z. The reliability of hip scoring systems for total hip arthroplasty candidates: assessment by physical therapists. Clin Rehabil 2005;19(6):659-661.</ref> | |||

*[[Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score]] <ref>Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, Riddle DL. The lower extremity functional scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. Phys Ther 1999;79:371-383.</ref><ref>Nilsdotter A, Bremander A. Measures of hip function and symptoms: Harris Hip Score (HHS), Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS), Oxford Hip Score (OHS), Lequesne Index of Severity for Osteoarthritis of the Hip (LISOH), and American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) Hip and Knee Questionnaire. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:S200-S207. </ref> | |||

==Physical Therapy Management== | |||

Physiotherapy interventions have been shown to improve ROM and strength in this patient population. Patients demonstrate greater improvement in muscle strength, functional mobility, gait speed, and quality of exercise performance. | |||

==== Physiotherapy Goals ==== | |||

* Reduce pain | |||

* Increase ROM | |||

* Increase strength | |||

* Patient to be independent with the appropriate assistive device and weight-bearing precautions | |||

* Improve balance | |||

* Improved efficiency in walking | |||

* | ===Conservative management=== | ||

* | Improve ROM: (see appendix 1 for exercise prescription). | ||

*Static stretch for lower extremity musculature. | |||

*Dynamic ROM. | |||

*Perform AROM and AAROM (active assistive range of motion) following passive stretching to maintain newly gained ROM. | |||

Improve strength: (see appendix 2 for exercise prescription). | |||

* Begin with isometric exercise and progress to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position with further .progression to isotonic exercises against gravity. It is appropriate to include concentric and eccentric contractions. | |||

* Begin with 2 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions of each exercise, with progression to 3 sets of each exercise to be used. | |||

* Local consensus would also do exercises to improve balance and gait and interventions to reduce pain.<ref name=":52">Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Evidence-based clinical care guideline for Conservative Management of Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease. Guideline 39. 2011. Available from: https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/-/media/cincinnati%20childrens/home/service/j/anderson-center/evidence-based-care/recommendations/type/legg-calve-perthes%20disease%20guideline%2039.</ref> | |||

The hip overloading pattern should be avoided in children with LCPD. Gait training to unload the hip might become an integral component of conservative treatment in children with LCPD. <ref>Švehlík M, Kraus T, Steinwender G, Zwick EB, Linhart WE. Pathological gait in children with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease and proposal for gait modification to decrease the hip joint loading. Int Orthop 2012;36(6):1235-1241.</ref> | |||

Non-surgical treatment with a brace is a reliable alternative to surgical treatment in LCPD between 6 and 8 years of age at onset with Herring B involvement. However, they could not know whether the good results were influenced by the brace or stemmed from having a good prognosis for these patients. <ref>Cıtlak A, Kerimoğlu S, Baki C, Aydın H. Comparison between conservative and surgical treatment in Perthes disease. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(1):87-92.</ref> | |||

===Post-operative management=== | |||

The rehabilitation is described regarding the various stages of rehabilitation. | |||

==== '''Initial Phase (0-2 weeks post-cast removal):''' ==== | |||

''The goals of the Initial Phase are:'' | |||

*Minimize pain | |||

*#Hot pack for relaxation and pain management with stretching. | |||

*#Cryotherapy. | |||

*#Medication for pain. | |||

*#Optimize ROM of hip, knee and ankle (see appendix 1 for exercises). | |||

*#Passive static stretch A hot pack may be used, based on patient preference and comfort. | |||

*#Dynamic ROM. | |||

*#Perform AROM and AAROM following passive stretching to maintain newly gained ROM. | |||

*Increase strength for hip flexion, abduction, and extension and knee and ankle (see appendix 2 for exercises). | |||

*#Begin with isometric exercises at the hip and progress to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position. | |||

*#Begin with isometric exercises at the knee and ankle, progressing to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position with further progression to isotonic exercises against gravity. | |||

*#Begin with 2 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions of each exercise with progression to 3 sets of each exercise to be used. | |||

*Improve gait and functional mobility. | |||

*#Follow the referring physician’s guidelines for WB status.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

*#Transfer training and bed mobility to maximize independence with ADL’s. | |||

*#Gait training with the appropriate assistive device, focusing on safety and independence. | |||

*Improving skin integrity. | |||

*#Scar massage and desensitization to minimize adhesions. | |||

*#Warm bath to improve skin integrity following cast removal, if feasible in the home environment. | |||

*#Warm whirlpool may be utilized if the patient is unable to safely utilize a warm bath for skin integrity management. | |||

PT is supervised at a frequency of 2-3 times per week (weekly). | |||

==== Intermediate Phase (2-6 weeks post-cast removal) ==== | |||

''Goals of the Intermediate Phase'' | |||

*Minimize pain (see ‘initial phase’) | |||

*#Normalize ROM of the knee and ankle and optimize ROM of the hip in all directions | |||

*#See ‘initial phase’ and see appendix 1 for exercises. | |||

* | *Increase strength of the knee and hip (see appendix 2 for exercises). | ||

* | *#Isotonic exercises of the hip in gravity lessened positions and advancing to against gravity positions. | ||

* | *#Isotonic exercises of the knee and ankle in gravity lessened and against gravity positions.<ref name=":2" /> | ||

*Maintain independence with functional mobility maintaining WB status and use of appropriate assistive devices. | |||

* | *Improving gait and functional mobility. | ||

* | *#Follow the referring physician’s guidelines for WB status. | ||

* | *#Continue gait training with the appropriate assistive device focusing on safety and independence. | ||

* | *#Begin slow walking in chest-deep pool water with arms submerged. | ||

*Improving Skin Integrity. | |||

*Continue with scar massage and desensitization. | |||

PT is supervised at a frequency of 2-3 times per week (weekly). It is recommended that activities outside of PT are restricted at this time due to WB status. If the referring physician allows, swimming is permitted. | |||

==== Advanced Phase (6-12 weeks post-cast removal) ==== | |||

''Goals'' | |||

*Minimize pain (see ‘initial phase’). | |||

*#optimize ROM and flexibility of the hip, knee, and ankle. | |||

*#see ‘initial phase’ and see appendix 1 for exercises. | |||

* | *Increase strength of the knee and hip, except for hip abductors, to at least 70% of the uninvolved lower extremity and increase strength of the hip abductors to at least 60% of the uninvolved lower extremity due to mechanical disadvantage (4 + 5) (see appendix 2 for exercises). | ||

*#Isotonic exercises of the hip, knee, and ankle in gravity lessened and against gravity positions, including concentric and eccentric contractions. | |||

*#WB and non-weight bearing (NWB) activities can be used in combination based on the patient’s ability and goals of the treatment session. | |||

*#Begin upper extremity supported functional dynamic single limb activities (e.g. step-ups, side steps). | |||

*#Continue with double limb closed chain exercises with resistance, progressing to single-limb closed chain exercises with light resistance if WB status allows. | |||

* | *#Use of a stationary bike in an upright or recumbent position keeping the hip in less than 90 degrees of flexion. | ||

* | |||

* | |||

* | |||

*Ambulation without the use of an assistive device or pain. | |||

*Negotiate stairs independently using a step to pattern with upper extremity (UE) support. | |||

*Improve balance to greater than 69% of the maximum Pediatric Balance Score (39/56) or single-limb stance of the uninvolved side. | |||

*Improving gait and functional mobility. | |||

PT is supervised at a frequency of 1-2 times per week (weekly). | |||

It is recommended that activities outside of PT are limited to swimming if the referring physician allows. | |||

Note: Running and jumping activities are restricted at this time. | |||

==== Pre-Functional Phase (12 weeks to 1+ year post-cast removal) ==== | |||

''Goals'' | |||

*Minimize pain (see ‘initial phase’). | |||

* | *Optimize ROM and flexibility of the hip, knee, and ankle. | ||

*#Static stretch | |||

* | *Increase strength of the knee and hip, except for hip abductors, to at least 80% of the uninvolved lower extremity and increase strength of the hip abductors to at least 75% of the uninvolved lower extremity due to mechanical disadvantage. | ||

*see ‘advanced phase’ and see appendix 1 for exercises. | |||

* | |||

*Negotiate stairs independently with reciprocal pattern and upper extremity support. | |||

*Improve balance to 80% or greater of the maximum Pediatric Balance Score (at least 45/56) or single-limb stance of the uninvolved side. | |||

*Non-painful gait pattern with minimal deficits and normal efficiency. | |||

PT is supervised at a frequency of 1-2 times per week (weekly). | |||

It is recommended that activities outside of PT include swimming and bike riding as guided by the referring physician. | |||

Note: Running and jumping activities are restricted at this time. | |||

==== Functional phase ==== | |||

''Goals'' | |||

*Reduce pain to 1/10 or less (see ‘initial phase’). | |||

*Normalizing ROM: Increase ROM to 90% or greater of the uninvolved side for the hip, knee, and ankle, except for hip abduction and Increase hip abduction ROM to 80% or greater due to potential bony block. | |||

*Normalizing strength: Increase strength of the knee and hip, except for hip abductors, to 90% or greater of the uninvolved lower extremity (5) and Increase strength of the hip abductors to at least 85% of the uninvolved lower extremity due to mechanical disadvantage (4+5). | |||

*#Progress isotonic exercises of the hip, knee, and ankle and include concentric and eccentric contractions. | |||

*#WB and NWB activities used in combination based on the patient’s ability (4) and goals of the treatment session. | |||

*#Functional dynamic single limb activities (e.g. step-ups, side steps) with upper extremity support as needed for patient safety. | |||

*#Progress single-leg closed chain exercises with resistance. | |||

*#Use of a stationary bike in an upright or recumbent position keeping the hip in less than 90 degrees of flexion. | |||

*Ambulation with a non-painful limp and normal efficiency. | |||

*Negotiation of stairs independently using a reciprocal pattern without UE support. | |||

*Improve balance to 90% or greater of the maximum score on the Pediatric Balance Scale (at least 51/56) or single-limb stance of the uninvolved side (5) It is recommended that progression to the Functional Phase occur when the physician has determined there is sufficient re-ossification of the femoral head based on radiographs (5). Note: Jumping and other impact activities are still limited and only progressed per instruction from the physician based on the healing and progression of the disease process. <ref name=":62">Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center: Evidence-based clinical care guideline for Post-Operative Management of Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease in children aged 3 to 12 years. Guideline 41. 2013. Available from: https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/-/media/cincinnati%20childrens/home/service/j/anderson-center/evidence-based-care/recommendations/type/legg-calve-perthes%20disease%20guideline%2041(2).</ref> | |||

=== Appendices === | |||

Appendix 1: ROM exercise prescription | |||

{| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" width="542" | {| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" width="542" | ||

|+ | |+ | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="col" | Intervention | ! scope="col" |Intervention | ||

! scope="col" | Parameters | ! scope="col" |Parameters | ||

! scope="col" | Intensity | ! scope="col" |Intensity | ||

! scope="col" | Notes | ! scope="col" |Notes | ||

! scope="col" | Muscle groups | ! scope="col" |Muscle groups | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Passive static stretch | |Passive static stretch | ||

| | |2 minutes of stretching per day, per muscle group | ||

2 minutes of stretching per day, per muscle group | |||

30 second hold time, doing 4 repetitions per muscle group | 30 second hold time, doing 4 repetitions per muscle group | ||

|Gentle static hold | |||

| | Within patient pain tolerance and without muscle guarding to prevent tissue damage and inflammatory response | ||

|This is the preferred method of stretching to gain flexibility and/or ROM | |||

Stretching to be done after warm-up, but before active exercises to maintain newly gained ROM | |||

| | |||

* · Hip adductors | |||

* · Hip internal rotators | |||

* Hip external rotators | |||

Stretching to be done after warm up, but | * Hip flexors | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |Dynamic ROM | ||

| 5 second hold, done with 24 repetitions per muscle group per day to meet 2 minute stretching time required | | 5-second hold, done with 24 repetitions per muscle group per day to meet 2-minute stretching time required | ||

| Self-selected intensity by patient as long as not causing pain | |Self-selected intensity by the patient as long as not causing pain | ||

| | |Done with patient activation of an antagonistic muscle group | ||

Done with patient activation of antagonistic muscle group | |||

| · Hip adductors | Done with slow movement to end range for full benefit | ||

| | |||

* · Hip adductors | |||

* · Hip internal rotators | |||

* Hip external rotators | |||

* Hip flexors | |||

|} | |} | ||

Appendix 2: Strengthening exercise prescription | |||

{| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" width="424" | {| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" width="424" | ||

|+ | |+ | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="col" | Intervention | ! scope="col" |Intervention | ||

! scope="col" | Parameters | ! scope="col" |Parameters | ||

! scope="col" | Intensity | ! scope="col" |Intensity | ||

! scope="col" | Notes | ! scope="col" |Notes | ||

! scope="col" | Muscle groups | ! scope="col" |Muscle groups | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Isometric strengthening | |Isometric strengthening | ||

| 10 seconds hold with 10 repetitions per muscle, for total of 100 seconds | |10 seconds hold with 10 repetitions per muscle, for a total of 100 seconds | ||

| Performed at approximately 75% maximal contraction | |Performed at approximately 75% maximal contraction | ||

| Performed with hip in neutral position | |Performed with hip in neutral position | ||

| Hip adductors | | | ||

* Hip adductors | |||

* · Hip internal rotators· Hip external rotators Hip flexors | |||

* · Hip extensors | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | |Isotonic strengthening | ||

| | |repetitions (10-15 reps) and 2 to 3 sets | ||

| Low resistance | Perform both concentric and eccentric contractions | ||

| | |Low resistance | ||

| Hip adductors | | | ||

| | |||

* Hip adductors | |||

* · Hip internal rotators· | |||

* Hip external rotators | |||

* Hip flexors· | |||

* Hip extensors | |||

|} | |} | ||

< | Table with levels of evidence of the guideline<ref name=":52" /><ref name=":62" /> | ||

< | |||

Appendix 3: Guide to levels of evidence referenced in guidelines. | |||

{| | {| class="wikitable" | ||

!Evidence level | |||

!Description | |||

|- | |- | ||

|1 | |||

|Systematic review, meta-analysis, or meta-synthesis of multiple studies | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | |2 | ||

| | |Best study design for domain | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |3 | ||

| | |Fair study design for domain | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |4 | ||

| | |Weak study design for domain | ||

|- | |- | ||

|5 | |||

|Local Consensus Other: General review, case report, consensus report, or guideline | |||

| 5 | |||

| Local consensus | |||

|} | |} | ||

==Clinical Bottom Line== | |||

Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease is an idiopathic juvenile [[Avascular Necrosis Femoral Head|avascular necrosis]] resulting in malformation of the femoral head. It’s a self-healing condition and the long term outcome and therapy strongly depends on the severity of the osteonecrosis and the ultimate shape of the femoral head. Although more prevalent amongst males, females generally have a worse outcome as well as do older children compared to younger ones. | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line | |||

Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease is an idiopathic juvenile avascular necrosis resulting in malformation of the femoral head. It’s a self healing condition and the long term outcome and therapy strongly depends on the severity of the osteonecrosis and the ultimate shape of the femoral head. Although more prevalent amongst males, females generally have worse outcome as well as do older children compared to younger ones. | |||

There is next to no empirical evidence due to a lack of experimental research and the therapies prescribed are mostly based on heuristic models. | |||

[[ | Treatments generally attempt to maintain and improve range of motion and strength as well as manage [[Pain Assessment|pain.]] | ||

==References== | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Hip]] | [[Category:Hip]] | ||

[[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | ||

[[Category:EIM_Residency_Project]] | [[Category:EIM_Residency_Project]] | ||

[[Category:Paediatrics]] | |||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | |||

[[Category:Younger Athlete]] | |||

[[Category:Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Paediatrics - Conditions]] [[Category:Paediatrics - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Hip - Conditions]] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:46, 30 July 2023

Original Editor - Pamela Gonzalez, Bahire Evelyne

Lead Editors - Sarah Haerinck, Admin, Evelyne Bahire, Pamela Gonzalez, Lucinda hampton, Fien Wijnant, Samuel Adedigba, Lauren Kwant, Abbey Wright, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Olajumoke Ogunleye, 127.0.0.1, Benjamin Desmedt, Rucha Gadgil, Wanda van Niekerk, Vidya Acharya, Eric Robertson, Blessed Denzel Vhudzijena, Meaghan Rieke, Jess Bell and Glenn Demeyer

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD), refers to idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral epiphysis seen in children.

It is a diagnosis of exclusion and other causes of osteonecrosis (including sickle cell disease, leukaemia, corticosteroid administration, Gaucher disease) must be ruled out.

Image 1: XRay - Bilateral Avascular Necrosis Femoral Head (Legg Calve Perthes Disease)

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The cause of LCPD is not known. It may be idiopathic or due to other aetiology that would disrupt blood flow to the femoral epiphysis, e.g. trauma (macro or repetitive microtrauma), coagulopathy, and steroid use. Thrombophilia is present in approximately 50% of patients, and some form of coagulopathy is present in up to 75%[1].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

LCPD disease is relatively uncommon and in Western populations has an incidence approaching 5 to 15:100,000.

- Boys are five times more likely to be affected than girls.

- Presentation is typically at a younger age than slipped upper femoral epiphysis (SUFE) with peak presentation at 5-6 years, but confidence intervals are as wide as 2-14 years.[2]

Pathology[edit | edit source]

The specific cause of osteonecrosis in LPCD disease is unclear.

Osteonecrosis generally occurs secondary to the abnormal or damaged blood supply to the femoral epiphysis, leading to fragmentation, bone loss, and eventual structural collapse of the femoral head. In approximately 15% of cases, osteonecrosis occurs bilaterally[2].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

A long bone has two parts: the diaphysis and the epiphysis. The diaphysis is the tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of the bone. The hollow region in the diaphysis is called the medullary cavity, which is filled with yellow marrow. The walls of the diaphysis are composed of dense and hard compact bone.[3]

Image 2: Anatomy of Long Bone, note epiphysis.

Presentation[edit | edit source]

LCPD is present in children 2-13 years of age and there is a four times the greater incidence in males compared to females. The average age of occurrence is six years.[4]

History

- Limp of acute or insidious onset, often painless (1 to 3 months).

- If pain is present, it can be localized to the hip or referred to the knee, thigh, or abdomen.

- With progression, pain typically worsens with activity.

- No systemic symptoms should be found.

Image 2: Trendelenburg gait

Physical Examination

- Decreased internal rotation and abduction of the hip.

- Pain on rotation referred to the anteromedial thigh and/or knee.

- Atrophy of thighs and buttocks from pain leading to disuse.

- Afebrile

- Limb-length discrepancy

Gait Evaluation

- Antalgic gait (acute): Short-stance phase secondary to pain in the weight-bearing leg.

- Trendelenburg gait (chronic): Downward pelvic tilt away from the affected hip during the swing phase[5].

Staging[edit | edit source]

Multiple classifications can be utilized to describe Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. The lateral pillar, or Herring, classification is widely accepted with the best interobserver agreement. It is generally determined at the beginning of the fragmentation stage, approximately 6 months after initial symptom presentation. It cannot be used accurately if the patient has not entered the fragmentation stage.

- Group A: The lateral pillar is at full height with no density changes. This group has a consistently good prognosis.

- Group B: The lateral pillar maintains greater than 50% height. There will be a poor outcome if the bone age is greater than 6.

- Group C: Less than 50% of the lateral pillar height is maintained. All patients will experience a poor outcome radiographically. The goal is to provide prognostic information. This classification is based on the height of the lateral pillar on the AP X-ray image.[1]

Treatment in Perthes disease is largely related to symptom control, particularly in the early phase of the disease. As the disease progresses, fragmentation and destruction of the femoral head occur. In this situation, operative management is sometimes required to either ensure appropriate coverage of the femoral head by the acetabulum or to replace the femoral head in adult life.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Goals of treatment include pain and symptom management, restoration of hip range of motion, and containment of the femoral head in the acetabulum.[1]

The younger the age at the time of presentation, the more benign disease course is expected, and also for the same age, the prognosis is better in boys than girls due to less maturity. Conservative treatment is favourable in children with a skeletal age of 6 years or less at the time of disease onset[2].

1. Nonoperative Treatment[edit | edit source]

- Indicated for children with bone age less than 6 or lateral pillar A involvement.

- Activity restriction and protective weight-bearing are recommended until ossification is complete.

- The patient may still take part in physical therapy.

- Literature does not support the use of orthotics, braces, or casts.

- NSAIDs can be prescribed for comfort.

- Referral to an experienced pediatric orthopedist is recommended.

2. Operative Treatment.[edit | edit source]

Femoral or Pelvic Osteotomy[1]

- Indicated in children over 8 years old.

- Outcomes are better in lateral pillar B and B/C with surgery compared to A and C

- Research suggests that surgery should be early before deformity of the femoral head develops.

Valgus or Shelf Osteotomies[1]

- Indicated in children who have hinge abduction.

- Results in improvements to the abductor mechanism

Hip Arthroscopy[1]

- Is becoming more common as a modality for mechanical symptoms and/or femoroacetabular impingement

Hip Arthrodiastasis[1]

- Considered a more controversial option.[1]

In later life, hip replacements may be necessary.[2]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Listed are some other disorders that should be included in the differential diagnosis for LCPD: All diseases which induce necrosis of the head or those resembling them are questioned in a differential diagnosis[5]:

- Slipped superior femoral epiphysis

- Osteomyelitis

- Secondary causes of osteonecrosis

- Dysplasia epiphyseal capitis femoris (Meyer dysplasia)

- Tumours

- Haemophilia

- Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis : a chronic inflammatory disorder that occurs before the age of 16 and can occur in all races. [6]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

An MRI is usually obtained to confirm the diagnosis; however, x-rays can also be of use to determine femoral head positioning.

Since LCPD has a variable end result, an imaging modality that can predict the outcome at the initial stage of the disease before significant deformity has occurred is ideal.

The extent of femoral head involvement depicted by non-contrast and contrast MRI showed no correlation at the initial stage of LCPD, indicating that they are assessing two different components of the disease process. In the initial stage of LCPD, contrast MRI provided a clearer depiction of the area of involvement. [7]

To quantify femoral head deformity in patients with LCPD novel three dimensional (3D) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reconstruction and volume-based analysis can be used. The 3D MRI volume ratio method allows accurate quantification and demonstrated small changes (less than 10 per cent) of the femoral head deformity in LCPD. This method may serve as a useful tool to evaluate the effects of treatment on femoral head shape.[8]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy interventions have been shown to improve ROM and strength in this patient population. Patients demonstrate greater improvement in muscle strength, functional mobility, gait speed, and quality of exercise performance.

Physiotherapy Goals[edit | edit source]

- Reduce pain

- Increase ROM

- Increase strength

- Patient to be independent with the appropriate assistive device and weight-bearing precautions

- Improve balance

- Improved efficiency in walking

Conservative management[edit | edit source]

Improve ROM: (see appendix 1 for exercise prescription).

- Static stretch for lower extremity musculature.

- Dynamic ROM.

- Perform AROM and AAROM (active assistive range of motion) following passive stretching to maintain newly gained ROM.

Improve strength: (see appendix 2 for exercise prescription).

- Begin with isometric exercise and progress to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position with further .progression to isotonic exercises against gravity. It is appropriate to include concentric and eccentric contractions.

- Begin with 2 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions of each exercise, with progression to 3 sets of each exercise to be used.

- Local consensus would also do exercises to improve balance and gait and interventions to reduce pain.[12]

The hip overloading pattern should be avoided in children with LCPD. Gait training to unload the hip might become an integral component of conservative treatment in children with LCPD. [13]

Non-surgical treatment with a brace is a reliable alternative to surgical treatment in LCPD between 6 and 8 years of age at onset with Herring B involvement. However, they could not know whether the good results were influenced by the brace or stemmed from having a good prognosis for these patients. [14]

Post-operative management[edit | edit source]

The rehabilitation is described regarding the various stages of rehabilitation.

Initial Phase (0-2 weeks post-cast removal):[edit | edit source]

The goals of the Initial Phase are:

- Minimize pain

- Hot pack for relaxation and pain management with stretching.

- Cryotherapy.

- Medication for pain.

- Optimize ROM of hip, knee and ankle (see appendix 1 for exercises).

- Passive static stretch A hot pack may be used, based on patient preference and comfort.

- Dynamic ROM.

- Perform AROM and AAROM following passive stretching to maintain newly gained ROM.

- Increase strength for hip flexion, abduction, and extension and knee and ankle (see appendix 2 for exercises).

- Begin with isometric exercises at the hip and progress to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position.

- Begin with isometric exercises at the knee and ankle, progressing to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position with further progression to isotonic exercises against gravity.

- Begin with 2 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions of each exercise with progression to 3 sets of each exercise to be used.

- Improve gait and functional mobility.

- Follow the referring physician’s guidelines for WB status.[5]

- Transfer training and bed mobility to maximize independence with ADL’s.

- Gait training with the appropriate assistive device, focusing on safety and independence.

- Improving skin integrity.

- Scar massage and desensitization to minimize adhesions.

- Warm bath to improve skin integrity following cast removal, if feasible in the home environment.

- Warm whirlpool may be utilized if the patient is unable to safely utilize a warm bath for skin integrity management.

PT is supervised at a frequency of 2-3 times per week (weekly).

Intermediate Phase (2-6 weeks post-cast removal)[edit | edit source]

Goals of the Intermediate Phase

- Minimize pain (see ‘initial phase’)

- Normalize ROM of the knee and ankle and optimize ROM of the hip in all directions

- See ‘initial phase’ and see appendix 1 for exercises.

- Increase strength of the knee and hip (see appendix 2 for exercises).

- Isotonic exercises of the hip in gravity lessened positions and advancing to against gravity positions.

- Isotonic exercises of the knee and ankle in gravity lessened and against gravity positions.[3]

- Maintain independence with functional mobility maintaining WB status and use of appropriate assistive devices.

- Improving gait and functional mobility.

- Follow the referring physician’s guidelines for WB status.

- Continue gait training with the appropriate assistive device focusing on safety and independence.

- Begin slow walking in chest-deep pool water with arms submerged.

- Improving Skin Integrity.

- Continue with scar massage and desensitization.

PT is supervised at a frequency of 2-3 times per week (weekly). It is recommended that activities outside of PT are restricted at this time due to WB status. If the referring physician allows, swimming is permitted.

Advanced Phase (6-12 weeks post-cast removal)[edit | edit source]

Goals

- Minimize pain (see ‘initial phase’).

- optimize ROM and flexibility of the hip, knee, and ankle.

- see ‘initial phase’ and see appendix 1 for exercises.

- Increase strength of the knee and hip, except for hip abductors, to at least 70% of the uninvolved lower extremity and increase strength of the hip abductors to at least 60% of the uninvolved lower extremity due to mechanical disadvantage (4 + 5) (see appendix 2 for exercises).

- Isotonic exercises of the hip, knee, and ankle in gravity lessened and against gravity positions, including concentric and eccentric contractions.

- WB and non-weight bearing (NWB) activities can be used in combination based on the patient’s ability and goals of the treatment session.

- Begin upper extremity supported functional dynamic single limb activities (e.g. step-ups, side steps).

- Continue with double limb closed chain exercises with resistance, progressing to single-limb closed chain exercises with light resistance if WB status allows.

- Use of a stationary bike in an upright or recumbent position keeping the hip in less than 90 degrees of flexion.

- Ambulation without the use of an assistive device or pain.

- Negotiate stairs independently using a step to pattern with upper extremity (UE) support.

- Improve balance to greater than 69% of the maximum Pediatric Balance Score (39/56) or single-limb stance of the uninvolved side.

- Improving gait and functional mobility.

PT is supervised at a frequency of 1-2 times per week (weekly).

It is recommended that activities outside of PT are limited to swimming if the referring physician allows.

Note: Running and jumping activities are restricted at this time.

Pre-Functional Phase (12 weeks to 1+ year post-cast removal)[edit | edit source]

Goals

- Minimize pain (see ‘initial phase’).

- Optimize ROM and flexibility of the hip, knee, and ankle.

- Static stretch

- Increase strength of the knee and hip, except for hip abductors, to at least 80% of the uninvolved lower extremity and increase strength of the hip abductors to at least 75% of the uninvolved lower extremity due to mechanical disadvantage.

- see ‘advanced phase’ and see appendix 1 for exercises.

- Negotiate stairs independently with reciprocal pattern and upper extremity support.

- Improve balance to 80% or greater of the maximum Pediatric Balance Score (at least 45/56) or single-limb stance of the uninvolved side.

- Non-painful gait pattern with minimal deficits and normal efficiency.

PT is supervised at a frequency of 1-2 times per week (weekly).

It is recommended that activities outside of PT include swimming and bike riding as guided by the referring physician.

Note: Running and jumping activities are restricted at this time.

Functional phase[edit | edit source]

Goals

- Reduce pain to 1/10 or less (see ‘initial phase’).

- Normalizing ROM: Increase ROM to 90% or greater of the uninvolved side for the hip, knee, and ankle, except for hip abduction and Increase hip abduction ROM to 80% or greater due to potential bony block.

- Normalizing strength: Increase strength of the knee and hip, except for hip abductors, to 90% or greater of the uninvolved lower extremity (5) and Increase strength of the hip abductors to at least 85% of the uninvolved lower extremity due to mechanical disadvantage (4+5).

- Progress isotonic exercises of the hip, knee, and ankle and include concentric and eccentric contractions.

- WB and NWB activities used in combination based on the patient’s ability (4) and goals of the treatment session.

- Functional dynamic single limb activities (e.g. step-ups, side steps) with upper extremity support as needed for patient safety.

- Progress single-leg closed chain exercises with resistance.

- Use of a stationary bike in an upright or recumbent position keeping the hip in less than 90 degrees of flexion.

- Ambulation with a non-painful limp and normal efficiency.

- Negotiation of stairs independently using a reciprocal pattern without UE support.

- Improve balance to 90% or greater of the maximum score on the Pediatric Balance Scale (at least 51/56) or single-limb stance of the uninvolved side (5) It is recommended that progression to the Functional Phase occur when the physician has determined there is sufficient re-ossification of the femoral head based on radiographs (5). Note: Jumping and other impact activities are still limited and only progressed per instruction from the physician based on the healing and progression of the disease process. [15]

Appendices[edit | edit source]

Appendix 1: ROM exercise prescription

| Intervention | Parameters | Intensity | Notes | Muscle groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive static stretch | 2 minutes of stretching per day, per muscle group

30 second hold time, doing 4 repetitions per muscle group |

Gentle static hold

Within patient pain tolerance and without muscle guarding to prevent tissue damage and inflammatory response |

This is the preferred method of stretching to gain flexibility and/or ROM

Stretching to be done after warm-up, but before active exercises to maintain newly gained ROM |

|

| Dynamic ROM | 5-second hold, done with 24 repetitions per muscle group per day to meet 2-minute stretching time required | Self-selected intensity by the patient as long as not causing pain | Done with patient activation of an antagonistic muscle group

Done with slow movement to end range for full benefit |

|

Appendix 2: Strengthening exercise prescription

| Intervention | Parameters | Intensity | Notes | Muscle groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isometric strengthening | 10 seconds hold with 10 repetitions per muscle, for a total of 100 seconds | Performed at approximately 75% maximal contraction | Performed with hip in neutral position |

|

| Isotonic strengthening | repetitions (10-15 reps) and 2 to 3 sets

Perform both concentric and eccentric contractions |

Low resistance |

|

Table with levels of evidence of the guideline[12][15]

Appendix 3: Guide to levels of evidence referenced in guidelines.

| Evidence level | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Systematic review, meta-analysis, or meta-synthesis of multiple studies |

| 2 | Best study design for domain |

| 3 | Fair study design for domain |

| 4 | Weak study design for domain |

| 5 | Local Consensus Other: General review, case report, consensus report, or guideline |

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease is an idiopathic juvenile avascular necrosis resulting in malformation of the femoral head. It’s a self-healing condition and the long term outcome and therapy strongly depends on the severity of the osteonecrosis and the ultimate shape of the femoral head. Although more prevalent amongst males, females generally have a worse outcome as well as do older children compared to younger ones.

There is next to no empirical evidence due to a lack of experimental research and the therapies prescribed are mostly based on heuristic models.

Treatments generally attempt to maintain and improve range of motion and strength as well as manage pain.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Mills S, Burroughs KE. Legg Calve Perthes Disease. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jul 13.Available:https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/24174/ (accessed 15.10.2021).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Radiopedia Perthes Disease Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/perthes-disease (accessed 15.10.2021).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hall JE. Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology e-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015 May 31.

- ↑ Herring JA, editor. Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease. 1st edition. Rosemont: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 1996 p.6-16.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Manig, M. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD). Principles of diagnosis and treatment. Orthopäde 2013;42(10):891-90.

- ↑ Hunter JB. (iv) Legg Calvé Perthes’ disease. Curr Orthopaed 2004;18(4):273-83.

- ↑ Kim, HK, Kaste, S, Dempsey M, Wilkes D. A comparison of non-contrast and contrast-enhanced MRI in the initial stage of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Pediatr Radiol 2013;43:1166.

- ↑ Standefer KD, Dempsey M, Jo C, Kim HKW. 3D MRI quantification of femoral head deformity in Legg‐Calvé‐Perthes disease." J Orthop Res 2016;35(9):2051-2058.

- ↑ Kirmit L, Karatosun V, Unver B, Bakirhan S, Sen A, Gocen Z. The reliability of hip scoring systems for total hip arthroplasty candidates: assessment by physical therapists. Clin Rehabil 2005;19(6):659-661.

- ↑ Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, Riddle DL. The lower extremity functional scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. Phys Ther 1999;79:371-383.

- ↑ Nilsdotter A, Bremander A. Measures of hip function and symptoms: Harris Hip Score (HHS), Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS), Oxford Hip Score (OHS), Lequesne Index of Severity for Osteoarthritis of the Hip (LISOH), and American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) Hip and Knee Questionnaire. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:S200-S207.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Evidence-based clinical care guideline for Conservative Management of Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease. Guideline 39. 2011. Available from: https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/-/media/cincinnati%20childrens/home/service/j/anderson-center/evidence-based-care/recommendations/type/legg-calve-perthes%20disease%20guideline%2039.

- ↑ Švehlík M, Kraus T, Steinwender G, Zwick EB, Linhart WE. Pathological gait in children with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease and proposal for gait modification to decrease the hip joint loading. Int Orthop 2012;36(6):1235-1241.

- ↑ Cıtlak A, Kerimoğlu S, Baki C, Aydın H. Comparison between conservative and surgical treatment in Perthes disease. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(1):87-92.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center: Evidence-based clinical care guideline for Post-Operative Management of Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease in children aged 3 to 12 years. Guideline 41. 2013. Available from: https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/-/media/cincinnati%20childrens/home/service/j/anderson-center/evidence-based-care/recommendations/type/legg-calve-perthes%20disease%20guideline%2041(2).