Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Ahmed M Diab (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (73 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors '''- [[User:Kirianne Vander Velden|Kirianne Vander Velden]] | '''Original Editors '''- [[User:Kirianne Vander Velden|Kirianne Vander Velden]] as part of the [[Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-based Practice Project|Vrije Universiteit Brussel's Evidence-based Practice project]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' -{{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' -{{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | |||

== Description == | == Description == | ||

[[ | Lateral [[Hip]] pain is a common orthopaedic problem. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS), previously known as trochanteric [[bursitis]], affects 1.8 per 1000 patients annually<ref name=":1" />. | ||

* GTPS is a clinical diagnosis of lateral hip pain and includes trochanteric bursitis associated with a [[tendinopathy]]<ref name=":38" /><ref name=":1" />; [[Gluteus Medius|gluteus]] [[Gluteus Medius|medius]] (GMed)/[[Gluteus Minimus|minimus]] (GMin) tendinopathy<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":29">Khoury AN, Brooke K, Helal A, Bishop B, Erikson L, Palmer IJ, Martin HD. [https://academic.oup.com/jhps/article/5/3/296/5068229?login=true Proximal iliotibial band thickness as a cause for recalcitrant greater trochanteric pain syndrome.] Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery. 2018;5(3):296–300.</ref>; tears of the gluteus medius or minimus tendons<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":4" /> and external coxa saltans<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":29" />. | |||

* Patients complain of pain over the lateral aspect of the thigh that is exacerbated with prolonged sitting, climbing stairs, high impact [[Physical Activity|physical activity]], or lying over the affected area. | |||

Previously, trochanteric bursitis was seen as the main pain source, but recent research indicates that the fluid within the bursa rather exists due to the gluteal tendinopathy and not because of | * The main bursae that are associated with GPTS are the [[Gluteus Minimus|gluteus minimus]], subgluteus medius, and the subgluteus maximus. | ||

* Previously, trochanteric bursitis was seen as the main pain source, but recent research indicates that the fluid within the bursa rather exists due to the gluteal tendinopathy and not because of primary inflammation in the bursa<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":38">Long SS, Surrey DE, Nazarian LN. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Levon-Nazarian/publication/258067149_Sonography_of_Greater_Trochanteric_Pain_Syndrome_and_the_Rarity_of_Primary_Bursitis/links/53ea681d0cf2fb1b9b67e456/Sonography-of-Greater-Trochanteric-Pain-Syndrome-and-the-Rarity-of-Primary-Bursitis.pdf Sonography of Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome and the Rarity of Primary Bursitis]. AJR. 2013;201:1083-1089.</ref><ref name=":37">Ali M, Oderuth E, Atchia I, Malviya A. [https://watermark.silverchair.com/hny027.pdf?token=AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW_Ercy7Dm3ZL_9Cf3qfKAc485ysgAAAr0wggK5BgkqhkiG9w0BBwagggKqMIICpgIBADCCAp8GCSqGSIb3DQEHATAeBglghkgBZQMEAS4wEQQM1S5J__Otk-KhSnb2AgEQgIICcIbUR_KyjGBVulJCpxZ55QTkOLg1EB4GAwNesynsxbn8NGs_4Mexp0z98hgsnZDdf6mHMvxwTmo6NUDVgI6_AuQH26dkQ0OCKnthiaMUDmKfOVaL8VmSUZ-Hxq19uHH3GsPlD4JrLCKykkCkM9pxYBwy1QE_xPRq1e8HNkq0eVrPKJMY0SlNmMecFjJHL9ckJKhnAFn210CDyQF346GLL5V1Qs7p4wIx-whn3PdAxB0AHAB2vwAqTiz1xjbMRwUk6vqF846HXB8BYwvAuc-npbVp_9BO0Do04g5k8zmCDiVsyYiIOyfzdbmgmc_aH9RUvPFnNNdokgOiNNfu6lhMAJMf-yGXN9D54Z5cIWWBYkOcHjg3qXvq7H_jhGyUcZJGCDmBB_HxZhPFYqnjkoHGQsKoFi5nZ8DavzyTBbiJy5KThbGMyC1ayrIEcUUgTyhevjtPdtUxL4bTtaWnoOuiAUTcdVcx9dU4WQgVQGkfkSQ7RgNnZujYbZ8zI1cpEoWZ9g_HA1rC8MYAa7GVZQsL0EmENPzfMvUq8SLYY3jhnnQuxDMJUcRfyL_eab7Oi7nvQJxVAh5lD627KjPIcUhFnhwmOJtZxkS5XrU2EGF3oFvJa-dpag5885HbQO195pj9HtGOX-44U30O8tGRcuzrDA4p7IkMVyO6j2oJbDAVKxlAM8wSTeohr0DK8Mpp95eIJ7gxIf4yrfuOfxtqVSvyrFGQyjQuaoSLLdfmcQ7UX0f2qAejGIi4N44tK6A9RUyWoILRwSRwJPC6dW_CMkDSJ7g2Cq9HrJrQijXiv9wOUmQMxXi0VgyT9-VKIc5SsYIxGg The use of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a systematic literature review.] Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery. 2018;5(3):209–219</ref>. The most recent research indicates GMed and GMin tendinopathy as the most frequent cause of GTPS<ref name=":8" /> <ref name=":37" /><ref name=":9" /><ref name=":10" />and managing the underlying tendinopathy should take priority<ref name=":2" />. | |||

The | The proposed clinical definition of GTPS: | ||

“A history of lateral hip pain and no difficulty with manipulating shoes and socks together with clinical findings of pain reproduction on palpation of the greater trochanter and lateral pain reproduction with the [[FABER Test|FABER]] test<ref name=":6">Fearon AM, Scarvell JM, Neeman T, Cook JL, Cormick W, Smith PN. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jennie_Scarvell/publication/230863767_Greater_trochanteric_pain_syndrome_Defining_the_clinical_syndrome/links/54eeece40cf2e55866f3b35f/Greater-trochanteric-pain-syndrome-Defining-the-clinical-syndrome.pdf Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: Defining the clinical syndrome]. Br J Sports Med. 2012;0:1–5.</ref>.” | |||

The GMax muscle tensions the ITB via its ITB attachment and assists with improving the hip joint’s passive stability< | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

[[File:Lateral Sling 1.png|right|frameless|557x557px]] | |||

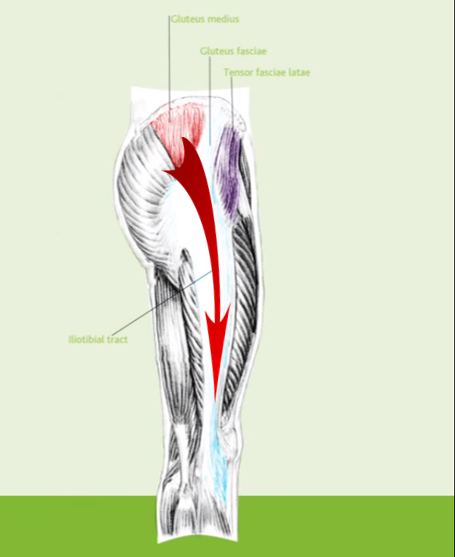

The greater trochanter is situated on the proximal and lateral side of the [[femur]], just distal to the hip joint and the neck of the femur. | |||

* The tendons of the [[Gluteus Medius|GMed]], GMin, [[Gluteus Maximus|gluteus maximus]] (GMax) and the [[Tensor Fascia Lata|tensor fascia lata]] (TFL) attach onto this bony outgrowth (apophysis). The greater trochanter is seen to have 4 facets and the above-mentioned [[muscle]] attachments have been equated to the “[[Rotator Cuff|rotator cuff]] of the hip”<ref name=":13">Bunker TD, Esler CAN, Leach WJ. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/William_Leach/publication/323333187_ROTATOR-CUFF_TEAR_OF_THE_HIP/links/5b3a155e4585150d23eeb18a/ROTATOR-CUFF-TEAR-OF-THE-HIP.pdf Rotator-cuff tear of the hip]. ''J Bone Joint Surg.'' 1997;79-B:618-620.</ref><ref name=":4">Domb BG, Carreira DS. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3716195/pdf/main.pdf Endoscopic Repair of Full-Thickness Gluteus Medius Tears.] Arthroscopy Techniques. 2013;2(2):e77-e81</ref>. | |||

* The external iliac fossa is the origin of the GMed and GMin muscles (GMed attaching to the lateral and superolateral facets and the GMin inserting onto the anterior facet). | |||

* The TFL lies over the GMed and GMin tendons and inserts onto the ITB<ref name=":12">Lin CY, Fredericson M. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Michael_Fredericson/publication/272409750_Greater_Trochanteric_Pain_Syndrome_An_Update_on_Diagnosis_and_Management/links/5b16dc4e45851547bba30c6b/Greater-Trochanteric-Pain-Syndrome-An-Update-on-Diagnosis-and-Management Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: An Update on Diagnosis and Management]. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2015;3(1);60-66.</ref>. | |||

On average, there are 6 bursae present around the lateral hip<ref>Woodley SJ, Mercer SR, Nicholson HD. [http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1015.2207&rep=rep1&type=pdf Morphology of the Bursae Associated with the Greater Trochanter of the Femur]. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:284-94.</ref>. The locations of these bursae vary greatly - the size, location and number are not consistent. | |||

* Four bursae are consistently present (multiple secondary bursa)<ref name=":14">Williams BS, Cohen SP. [http://drkney.com/pdfs/GTBursa.pdf Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: A Review of Anatomy, Diagnosis and Treatment.] International Anesthesia Research Society. 2009;108(5):1662-1670.</ref>. | |||

* The three chief bursae at the hip include tsub gluteuseus maximus, sub gluteusteus minimus andsub gluteusuteus medius bursa<ref name=":12" />. | |||

* These bursae and the periosteum of the greater trochanter are innervated by a small branch of the femoral nerve<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":15">Genth B. Von Düring M, Von Engelhardt LV, Ludwig J, Teske W, Von Schulze-Pellengahr C. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ca.22035 Analysis of the sensory innervations of the greater trochanter for improving the treatment of greater trochanteric pain syndrome]. Clin Anat. 2012 Nov;25(8):1080-6.</ref>. | |||

Hip joint stability | |||

* GMax muscle tensions the ITB via its ITB attachment and assists with improving the hip joint’s passive stability<ref name=":17">Louw M, Deary C. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maryke_Louw/publication/255974740_The_biomechanical_variables_involved_in_the_aetiology_of_iliotibial_band_syndrome_in_distance_runners_-_A_systematic_review_of_the_literature/links/5a5de7e6458515c03edfa5bb/The-biomech The biomechanical variables involved in the aetiology of iliotibial band syndrome in distance runners–A systematic review of the literature.] Physical TheraSport sport. 2014 Feb 1;15(1):64-75.</ref>. | |||

* ITB is also tensioned by the [[Vastus Lateralis|vastus lateralis and]] TFL and limits hip internal rotation and adduction passively<ref name=":17" />. | |||

* GMed prevents excessive hip adduction and is often seen as the primary stabilizer of the pelvis<ref name=":17" />. | |||

Hip joint innervation includes the rami articulares of the obturator nerve, the [[Femoral Nerve|femoral nerve]], [[Sciatic Nerve|sciatic nerve]]<ref>Fernandez E, Gastaldi P. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0720048X11003706 Hip pain from orthopaedic point of view]. European journal of radiology. 2012 Dec 1;81(12):3737-9.</ref> and a branch of the femoral nerve that supplies the periosteum and bursae of the greater trochanter. | |||

== Epidemiology== | |||

*Lateral hip pain affects 1.8 out of 1000 patients annually<ref name=":1" />. | |||

* Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is most prevalent between the fourth and sixth decades of life<ref name=":5" />. | |||

* Studies have shown that GTPS has a strong correlation with the female gender and [[obesity]].<ref name=":0">Gomez LP, Childress JM. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557433/ Greater Trochanteric Syndrome (GTS, Hip Tendonitis)]. InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 May 6. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557433/ (last accessed 24 December 2023)</ref> | |||

== Aetiology | == Aetiology== | ||

Since GMed and GMin tendinopathy, tears of the GMed and GMin tendons, external coxa saltans and ITB abnormalities can all be possible causes of GTPS, the aetiology of each of these structures/pathologies need to be considered. | |||

Tendinopathy aetiology: | |||

* The exact mechanism is still unknown<ref name=":5" />. | |||

* Overuse<ref name=":5" /> | |||

* Mechanical overload<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":10" /> | |||

* Incomplete or failed healing<ref name=":5" /> | |||

* Compression of the tendon at the enthesis <ref name=":10" /> | |||

In people with weak hip abductors, particularly GMed, greater hip adduction is seen causing increased compression of the GMed and GMin tendons at the greater trochanter. With the increased adduction, the ITB exerts higher compressive forces on the gluteal tendons, amplifying the compression | * In people with weak hip abductors, particularly GMed, greater hip adduction is seen causing increased compression of the GMed and GMin tendons at the greater trochanter. With the increased adduction, the ITB exerts higher compressive forces on the gluteal tendons, amplifying the compression<ref name=":2">Jacobson JA, Yablon CM, Henning PT, Kazmers FS, Urquhart A, Hallstrom B, Bedi A, Parameswaran A. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.7863/ultra.15.11046 Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: Percutaneous Tendon Fenestration Versus Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection for Treatment of Gluteal Tendinosis]. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:2413–2420.</ref>. Hip positions in higher ranges of flexion may also increase the compression of the GMed and GMin tendons due to increased tension in the ITB, explaining why pain that occurs with prolonged sitting<ref name=":10">Grimaldi A, Mellor R, Hodges P, Bennell K, Wajswelner H, Vicenzino B. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bill_Vicenzino/publication/276362252_Gluteal_Tendinopathy_A_Review_of_Mechanisms_Assessment_and_Management/links/555db77208ae8c0cab2af237/Gluteal-Tendinopathy-A-Review-of-Mechanisms-Assessment-and-Management.pdf Gluteal Tendinopathy: A Review of Mechanisms, Assessment and Management]. Sports Med. 2015;45(8):1107-1119.</ref>. | ||

* Pelvic control in a single leg stance position - controlled 70% by the abductor muscles and the ITB tensioners (GMax, TFL and vastus lateralis) account for the remaining 30%<ref name=":10" />. People with gluteal tendinopathy tend to have GMed and GMin atrophy and TFL hypertrophy. Weakness and/or muscle bulk changes impact the balance of the abductor mechanism and increase the compression of the gluteal tendons<ref name=":10" />. | |||

* Women are more prone to GTPS because of pelvic biomechanics, different activity levels in the population and hormonal effects<ref name=":12" />. Females have a smaller insertion of the GMed tendon, resulting in a smaller area across which tensile load could be dissipated and a shorter moment arm, causing reduced mechanical efficiency<ref name=":8">Grimaldi A, Fearon A. [https://www.jospt.org/doi/pdf/10.2519/jospt.2015.5829 Gluteal Tendinopathy: Integrating Pathomechanics and Clinical Features in Its Management]. JOSPT. 2015;45(11):910-924.</ref>. | |||

* Increased fluid within the bursa is thought to be a consequence of the tendinopathy rather than it being due to inflammation of the bursa.<ref name=":7">Fearon AM, Twin J, Dahlstrom JE, Cook JL, Cormick W, Smith PN, Scott A. I[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4856521/pdf/increased substance P expression in the trochanteric bursa of patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome]. Rheumatol Int. 2014; 34(10):1441–1448.</ref>. | |||

Tears of the GMed and GMin tendons | [[Tendon Load and Capacity|Tears]] of the GMed and GMin tendons: | ||

* A frequently missed cause of GTPS<ref name=":18">Domb BG, Nasser RM, Botser IB. [https://www.americanhipinstitute.org/pdf/partial-thickness-tears-gluteus-medius-techniques-transtendinous-endoscopic-repair-2010.pdf Partial-thickness tears of the gluteus medius: rationale and technique for trans-tendinous endoscopic repair]. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2010 Dec 1;26(12):1697-705.</ref>. | |||

* Up to 25% of middle-aged women can have GMed tears. It is also found in up to 10% of middle-aged men<ref name=":18" />. | |||

* Tears can be acute but degenerative tears are far more common. It was thought that the GMed tendon was most frequently affected<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":18" /> but a study published in 2020 revealed that GMin tendons tears were more frequent than GMed tears<ref name=":3">Zhu M, Smith B, Krishna S, Musson DS, Riordan PR, McGlashan SR, Cornish J, Munro JT. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_url?url=https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-25400/latest.pdf&hl=en&sa=T&oi=gsb-ggp&ct=res&cd=0&d=286002700427120231&ei=-67xXqSuBoKOmgGwn6jwDQ&scisig=AAGBfm3JBaFl6PC7ixpDsPjbcLs-SFe6jw The Pathological Features of Hip Abductor Tendon Tears–A Cadaveric Study.]</ref>. GMed and GMin tears were associated with tendon and enthesis degeneration<ref name=":3" />. | |||

* Tears at the GMed tendon insertion can be complete, intrasubstance or partial, with partial tears occurring most frequently<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":18" />. Complete tears of the GMed are associated with a coinciding GMin tear but MRI and ultrasound investigations very rarely identify the GMin tear<ref name=":3" />. | |||

* Most tears are found at the insertion of the anterior and middle portions of the GMed and GMin tendons. | |||

Coxa saltans or | Coxa saltans or Snapping Hip Syndrome: | ||

* Presents in about 5% to 10% of the general population<ref name=":19">Lewis CL. E[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3445103/pdf/10.1177_1941738109357298.pdf xtra-articular snapping hip: a literature review]. Sports health. 2010 May;2(3):186-90.</ref>. | |||

* Most commonly found in dancers and professional athletes, but can also occur due to physical trauma<ref name=":19" />. | |||

* It can be intra-articular or extra-articular<ref name=":19" /> , with the extra-articular presentation being relevant to GTPS. | |||

* Extra-articular coxa sultans most commonly involve the anterior part of GMax or the posterior ITB snapping over the greater trochanter, causing a catching or sensation of “giving way” and an inflammatory response in the trochanteric bursa.<ref name=":19" /><ref name=":20">Yen YM, Lewis CL, Kim YJ. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4961351/pdf/nihms721941.pdf Understanding and treating the snapping hip]. Sports medicine and arthroscopy review. 2015 Dec;23(4):194.</ref>. | |||

* There is often an imbalance between TFL and GMax activation in these patients<ref name=":20" />. | |||

* Patients can report a sensation of subluxation and worse pain with activities such as climbing stairs, hiking and running<ref name=":19" />. There are, however, patients who do not experience pain when it snaps<ref name=":20" />. | |||

Patients presenting with GTPS often have [[Low Back Pain|low back pain]]<ref name=":5">Reid D. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4761624/pdf/main.pdf The management of greater trochanteric pain syndrome: A systematic literature review.] Journal of Orthopaedics. 2016;13:15-28.</ref><ref name=":8" /><ref name=":11">Nissen MJ, Brulhart L, Faundez A, Finckh A, Courvoisier DS, Genevay S. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Michael_Nissen/publication/327943613_Glucocorticoid_injections_for_greater_trochanteric_pain_syndrome_a_randomised_double-blind_placebo-controlled_GLUTEAL_trial/links/5bb1daf6a6fdccd3cb80aac3/Glucocorticoid-injections- Glucocorticoid injections for greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled (GLUTEAL) trial]. Clinical Rheumatology. 2018;38(3):647-655.</ref> or hip joint [[Osteoarthritis|OA]]<ref name=":5" />. There is also a higher occurrence of GTPS in people with ITB syndrome and [[Knee Osteoarthritis|knee OA]]<ref name=":23">McEvoy JR, Lee KS, Blankenbaker DG, Rio AMD Keene JS. [https://www.ajronline.org/doi/pdfplus/10.2214/AJR.12.9443 Ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injections for treatment of greater trochanteric pain syndrome: greater trochanter bursa sub gluteus medius bursa]. ''American Journal of Roentgenology'', 2013; ''201''(2):W313-W317.</ref><ref name=":12" />. | |||

There is no clear evidence that a leg length discrepancy has any impact on a person developing GTPS | There is no clear evidence that a leg length discrepancy has any impact on a person developing GTPS<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":12" />. | ||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation== | == Characteristics/Clinical Presentation== | ||

GTPS typically presents with lateral hip pain that may radiate down the lateral thigh and buttocks and occasionally to the lateral knee. It can be described as aching and intense at times of greater aggravation caused by passive, active and resisted hip abduction and external rotation | GTPS typically presents with lateral hip pain that may radiate down the lateral thigh and buttocks and occasionally to the lateral knee. It can be described as aching and intense at times of greater aggravation caused by passive, active and resisted hip abduction and external rotation<ref name=":16">Shbeeb MI, Matteson EL. Trochanteric bursitis (greater trochanter pain syndrome). InMayo Clinic Proceedings 1996 Jun 1 (Vol. 71, No. 6, pp. 565-569). Elsevier.</ref>. It is often characterised by the ‘jump’ sign where palpation of the greater trochanter causes the patient to nearly jump off the bed<ref name=":1">Speers CJB, Bhogal GS. [https://bjgp.org/content/bjgp/67/663/479.full.pdf Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a review of diagnosis and management in general practice]. British Journal of General Practice. 2017;67:479-480.</ref>. | ||

The symptoms include: | The symptoms include: | ||

* Tender lateral hip when palpated, especially near the greater trochanter< | * Tender lateral hip when palpated, especially near the greater trochanter<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":9">Klauser AS, Martinoli C, Tagliafico A, Bellmann-Weiler R, Feuchtner GM, Wick M, Jaschke WR. [https://www.thieme-connect.de/products/ejournals/pdf/10.1055/s-0033-1333913.pdf Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome]. Seminars in Musculoskeletal Radiology. 2013;17(1):43-48.</ref><ref name=":8" /><ref name=":4" /><ref name=":18" /> | ||

* Pain with side-lying on the problematic side< | * Pain with side-lying on the problematic side<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":9" /><ref name=":8" /><ref name=":21">Ganderton C, Semciw A, Cook J, Moreira E, Pizzari T. G[https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/jwh.2017.6729 luteal loading versus sham exercises to improve pain and dysfunction in postmenopausal women with greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trial]. Journal of Women's Health. 2018 Jun 1;27(6):815-29.</ref> | ||

* Pain with weight-bearing activities such as walking, climbing stairs, standing and running< | * Pain with [[Weight bearing|weight-bearing]] activities such as walking, climbing stairs, standing and running<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":9" /><ref name=":8" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":18" /><ref name=":21" /><ref name=":22">Fearon A, Neeman T, Smith P, Scarvell J, Cook J. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Angela_Fearon2/publication/251677018_Greater_trochanteric_pain_syndrome_is_not_a_benign_condition_to_be_ignored/links/586b447f08aebf17d3a4d6e8/Greater-trochanteric-pain-syndrome-is-not-a-benign-condition-to-be-ignored. Pain, not structural impairments may explain activity limitations in people with gluteal tendinopathy or hip osteoarthritis cross-sectional study]. Gait & posture. 2017 Feb 1;52:237-43.</ref> | ||

* Pain may refer to the lateral thigh and knee< | * Pain may refer to the lateral thigh and knee<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":8" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":4" /> | ||

* Pain with prolonged sitting< | * Pain with prolonged sitting<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":21" /> | ||

* Pain with resisted abduction< | * Pain with resisted abduction<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":18" /> | ||

* Sitting with crossed legs increases pain | * Sitting with crossed legs increases pain<ref name=":8" /> | ||

* Pain can also occur when lying on the non-painful side if the painful hip falls into adduction | * Pain can also occur when lying on the non-painful side if the painful hip falls into adduction | ||

* Pain is usually episodic and will worsen over time with continued aggravation | * Pain is usually episodic and will worsen over time with continued aggravation | ||

* Weak hip abductors< | * Weak hip abductors<ref name=":22" /> | ||

== Differential Diagnosis== | == Differential Diagnosis== | ||

[[File:Differential diagnosis of lateral hip pain.png|714x714px|Differential diagnosis of lateral hip pain.|right|frameless]] | |||

To be able to treat GTPS correctly, accurate differential diagnosis is crucial<ref name=":6" />. Conditions that may mimic GTPS include the following: | |||

* Hip OA<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":22" /><ref name=":12" /><ref name=":10" /><ref name=":8" />. Similar site of symptoms, aggravated by weight-bearing activity and weakness in hip abductors<ref name=":22" />. | |||

* [[Avascular necrosis of the femoral head|Femoral head avascular necrosis]] (AV)<ref name=":24">Klontzas ME, Karantanas AH. [https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/44262524/Greater_trochanter_pain_syndrome_A_descr20160331-32038-1sdfgs7.pdf?response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DGreater_trochanter_pain_syndrome_A_descr.pdf&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A%2F20200315%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20200315T164409Z&X-Amz-Expires=3600&X-Amz-Si Greater trochanter pain syndrome: a descriptive MR imaging study.] European journal of radiology. 2014 Oct 1;83(10):1850-5.</ref><ref name=":12" /> | |||

* Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)<ref name=":24" /><ref name=":12" /><ref name=":8" /> | |||

* Lumbar spine referral or degenerative disease<ref name=":24" /><ref name=":10" /><ref name=":8" /> | |||

* Femoral-head stress fractures<ref name=":12" /> | |||

* [[Labral Tear|Labral tears]]<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":8" /> | |||

* Bony metastasis<ref name=":8" /> | |||

* Neck-of-femur fracture<ref name=":8" /> | |||

* Inflammatory disease such as [[Rheumatoid Arthritis|RA]]<ref name=":8" /> | |||

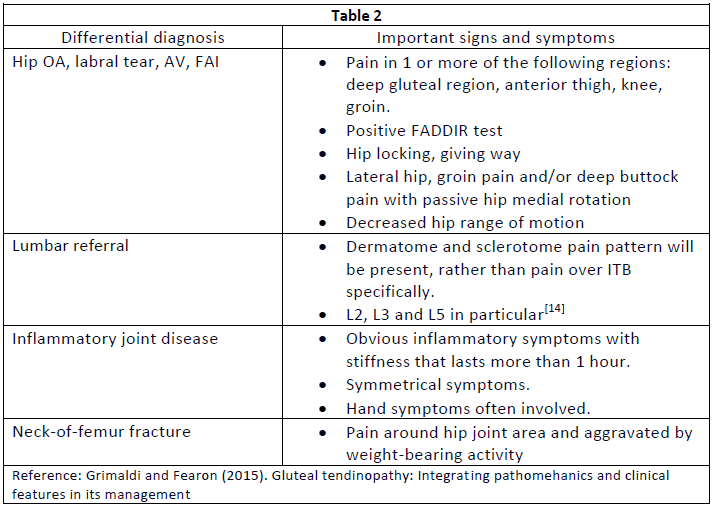

Table 2 includes some important signs and symptoms of the differential diagnoses<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":12" />: | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures== | |||

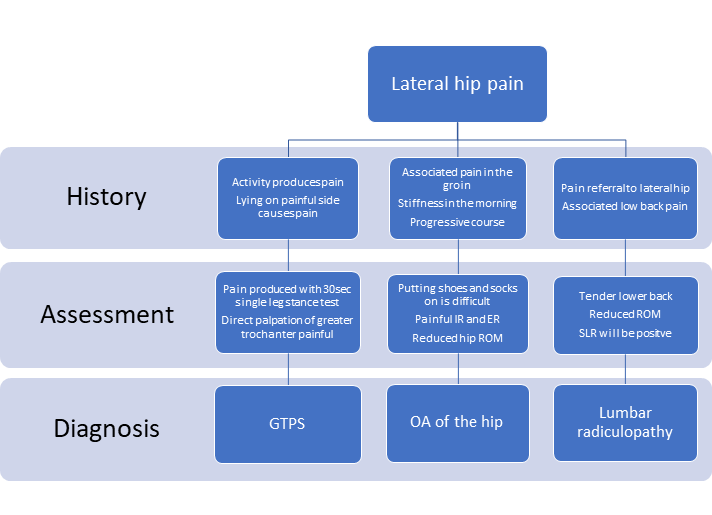

[[File:Common causes of lateral hip pain.png|712x712px|Common causes of lateral hip pain [Speers and Bhogal (2017)]|frameless|alt=|right]] | |||

There is no one specific test to confirm GTPS and the tests available lack validity when done in isolation. | |||

Diagnostic accuracy can however be improved when a combination of tests is used<ref name=":1" />. | |||

* The single leg stance test for 30 seconds has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 100% and al has very high sensitivity when pain is produced within 30 seconds of standing on the painful side<ref name=":1" /><sup>,</sup><ref name=":12" />. | |||

* Resisted hip medial rotation, lateral rotation and abduction can also be used to assess for GTPS. Resisted lateral rotation has the highest sensitivity (88%) and specificity (97.3%) when compared to resisted medial rotation and abduction<ref name=":8" />. The highest specificity is achieved when the test is done in 90° hip flexion<ref name=":10" />. | |||

* FADER, OBER and FABER - aim to increase the tensile load on the gluteal tendons<ref name=":1" />. | |||

* The ability to put one’s socks and shoes on without help will also help differentiate GTPS from OA, where the GTPS patient has no difficulty during activity <ref name=":1" />. | |||

* The “jump sign” carries a PPV of 83% so direct palpation of the greater trochanter helps to diagnose GTPS<ref name=":1" />. | |||

* The Trendelenburg sign is present in patients with GTPS and when used to assess for a GMed tear, it has a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 77%<ref name=":12" />. | |||

* If external coxa saltans is suspected - FABER, Ober test, Hula-Hoop test and active hip flexion followed by passive extension and abduction<ref>Via AG, Fioruzzi A, Randelli F. D[https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322651081_Diagnosis_and_Management_of_Snapping_Hip_Syndrome_A_Comprehensive_Review_of_Literature in diagnosis and Management of Snapping Hip Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review of Literature.] Rheumatology (Sunnyvale). 2017;7(228):2161-1149.</ref>. | |||

Imaging is only suggested in the following situations: | |||

* When gluteal tears are suspected. Ultrasound or MRI can be used to confirm the diagnosis if suspected clinically<ref name=":18" /><ref name=":12" />. Cook (2020) reports that ultrasound is the most accurate when assessing a tendon where MRI is helpful for differential diagnosis<ref name=":25">Cook J. Lower Limb Tendinopathy. Lower Limb Tendinopathy course; 2020 Mar 9-10; Cape Town, South Africa. P1-102.</ref>. | |||

* When conservative treatment has failed<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":8" />. | |||

* When diagnosis is unclear<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":12" />. | |||

Above is a diagnostic flow chart created by Speers and Bhogal (2017) for the 3 most common causes of lateral hip pain<ref name=":1" />. | |||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

* [https://www.docdroid.net/14r9c/visa-g-with-scoring.pdf VISA-G] - GTPS-specific outcome measure<ref>Fearon AM, Ganderton C, Scarvell JM, Smith PN, Neeman T, Nash C, Cook JL. [https://core.ac.uk/reader/156625870 Development and validation of a VISA tendinopathy questionnaire for greater trochanteric pain syndrome, the VISA-G.] Manual therapy. 2015 Dec 1;20(6):805-13.</ref> | |||

* | * [[Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score|HOOS]] - Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score | ||

* | * [[Harris Hip Score|HHS]] - Harris Hip Score | ||

* Lumbar spine | * [[International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT)|iHOT]] - International Hip Outcome Tool | ||

== Examination== | |||

GTPS is a clinical diagnosis which means the diagnosis is based on the medical history as well as the signs and symptoms. The assessment should include the following: | |||

* A good subjective assessment to gather the necessary information regarding the signs and symptoms. | |||

* Hip joint assessment | |||

* Lumbar spine - this needs to be excluded as a possible cause of the pain. | |||

* Special tests. These can be used to help confirm or negate the suspected diagnosis of GTPS. In 2017, Ganderton et al. validated the following tests for GTPS: FABER, resisted external de-rotation test, greater trochanter palpation and resisted abduction<ref name=":26">Ganderton C, Semciw A, Cook J, Pizzari T. [https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9ffe/ea3c628dfa9e7351f8301808e8d1ae13ea4a.pdf Demystifying the clinical diagnosis of greater trochanteric pain syndrome in women. Journal of Women's Health]. 2017 Jun 1;26(6):633-43.</ref> (Click on the link to each test for more detailed information and/or a video regarding each test). | |||

'''[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Trendelenburg_Test Trendelenburg Test]''': This is a quick test for assessing hip abductor muscle function and it can also be used to help determine if a tear is present in the hip abductors. A drop of the pelvis on the contralateral side of the stance leg indicates weakness of the stance leg's hip abductors and results in a positive test. Test administration is demonstrated [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lBSXrZCP4So here]. | |||

'''[http://www.physio-pedia.com/FABER_Test FABER Test]''': FABER is the acronym for flexion, abduction, and external rotation. It is very helpful in confirming GTPS<ref name=":6" /> and it assists with differentiating between hip OA and GTPS<ref name=":1" />. | |||

'''[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Noble's_test Noble Test]''': This is used to verify Iliotibial tightness and helps to distinguish iliotibial tightness from other common causes of lateral knee pain, such as lateral collateral ligament strain, bicipital or popliteal tendinopathy, knee OA and lateral meniscal pathology<ref>Dubin J. [http://dubinchiro.com/illiotibial_band.pdfEvidence-Basedd Treatment for Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome: Review of Literature.] BioMechanics 2005.</ref>. Test administration is demonstrated [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IIJVbf_t_2A here]. | |||

'''[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Ober's_Test Modified Ober’s Test]'' ': This test and its modification are used to assess the TFL and ITB. The test is positive if the thigh does not go further than 10 degrees of adduction. | |||

'''[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Renne_test Renne’s Test]''': This test is used to assess ITB syndrome and can be done alone or in conjunction with the Noble Test. | |||

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PzaeZjsVs5Q 'secondsecond ) Single leg stance test:'''] The person being tested must stand, unassisted, on one leg with their eyes open and one finger on a wall. As soon as the person’s foot is lifted off the floor, the 30 seconds start. A positive test for patients with GTPS is lateral hip by 30 seconds. Grimaldi and Fearon (2015) suggest holding the position the until reproduction of symptoms<ref name=":8" />. | |||

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Aq3R ipz4Jjw '''Resisted external de-rotation test'''] and modified external de-rotation test: The patient lies in supine and the examiner then passively flexes the hip to 90° with external rotation. The hip should be in neutral abduction/adduction. Slightly reduce the external rotation to decrease the compression of the tendon. The patient then actively rotates their leg to neutral against the therapist’s resistance. The modification is the same, but done in full hip adduction.<ref name=":26" /> | |||

'''[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=goJXyusCCzA Resisted abduction test]''': The examiner passively abducts the testing-limb to 45° abduction with the patient in side-lying or supine. The patient must then maintain this position against the examiner’s resistance. The resistance must be applied 1cm superior to the lateral malleolus<ref name=":26" />. This test has a 73% sensitivity and 87% specificity for GMed pathology<ref name=":36">Ortiz-Declet V, Chen AW, Maldonado DR, Yuen LC, Mu B, Domb BG. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6990389/ Diagnostic accuracy of a new clinical test (resisted internal rotation) for detection of gluteus medius tears]. J Hip Preserv Surg. 2019 Nov 14;6(4):398-405. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnz046. </ref>. | |||

'''Resisted internal rotation''': This test has a 92% sensitivity, 85% specificity and 88% accuracy for diagnosing GMed tears . To perform the test, place the problematic limb into 90° hip and knee flexion with 10° hip external rotation while the patient is supine. While the examiner provides resistance to the movement, the patient must perform active hip internal rotation. The test is positive if the patient experiences pain and/or weakness.<ref name=":36" /> | |||

Diagnostic test clusters: Combination of palpation with resisted hip abduction in either abduction or adduction position can be useful in both ruling in or out GTPS. However, a 30-second single-leg stance may help in confirming a positive diagnosis. | |||

== Management == | |||

The initial approach to treat Greater trochanteric pain syndrome includes a range of conservative interventions such as physiotherapy, local corticosteroid injection, PRP injection, shockwave therapy (SWT), activity modification, pain-relief and anti-inflammatory medication and weight reduction. | |||

* Most are resolved with conservative measures, with success rates of over 90%. For the majority of the cases, GTPS is self-limiting<ref name=":0" />. | |||

'''Non-Surgical Intervention''' | |||

Non-surgical treatment options include the following: | |||

* Physiotherapy, which includes manual therapy and therapeutic exercise | |||

* Low energy [[Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy |extracorporeal shockwave therapy]] (ESWT) | |||

* [[Therapeutic Corticosteroid Injection|Corticosteroid injection]] is effective in the short-term only<ref name=":28" /> (3 to 4 months<ref name=":10" />) and is advised for bursitis rather than tendinopathy<ref name=":12" />. It is more effective to inject the greater trochanteric bursa than the subgluteus medius bursa<ref name="Platelet-rich plasmaRich Plasma found to be a feasible alternative but it is unknown whether it or corticosteroids are more effective. This [[Lateral Epicondyle Tendinopathy Toolkit: Appendix G - Medical and Surgical Interventions|link]] has an explanation of PRP injections | |||

* [[Pain Medications|Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs]] (NSAIDs) may help with analgesia in the acute phase or prim [[bursitis]], but it is not advised in chronic gluteal tendinopathy or gluteal tendon tears as NSAIDs have been found to potentially have a neghurtaling<ref name=":12" />. | |||

== Physiotherapy == | |||

Exercise is promoted from early in treatment for tendinopathy and the main goals should include<ref name=":1" />: | |||

* [[Load Management|Load management]] | |||

* Reduction of compressive forces | |||

* Strengthening of the [[Gluteal Tendinopathy|gluteal muscle]]<nowiki/>s and | |||

* Management of any co-morbidities | |||

See comprehensive exercise treatment regimes further below | |||

'''Therapeutic Modalities''' | |||

* ESWT was found to be more effective than corticosteroid injections and multimodal therapy at a 1-year follow-up. The long-term 1-year of ESWT is however controversial<ref name=":28" />. A study that combined exercise and ESWT found that this approach was superior to corticosteroid injection for pain relief at 15 months follow-up<ref name=":12" />. | |||

* [[Dry Needling|Dry-needling]] is a commonly-used intervention in commonly used A study published in 2017 compared dry-needling to corticosteroid injections for pain relief in GTPS and found that corticosteroid injections did not offer greater pain relief or to dry-needling. There was also no difference in function improvement between the two groups. Based on this, dry needling may be a viable option for pain relief in GTPS<ref>Brennan KL, Allen BC, Maldonado YM. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328761927_Dry_needling_in_addition_to_standard_physical_therapy_treatment_for_sub-acromial_pain_syndrome_a_randomized_controlled_trial_protocol Dry Needling Versus Cortisone Injection in the Treatment of Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: A Noninferiority Randomized Clinical Trial]. Journal of orthopaedic ''&'' sports physicOrthopaedic 2017;47(4):232-239.</ref>. | |||

* Other modalities like [[Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)|TENS]], cross-frictions and low-level laser have not been assessed properly for GTPS<ref name=":31">Wyss J, Patel A. [http://zu.edu.jo/UploadFile/Library/E_Books/Files/LibraryFile_171033_57.pdf Therapeutic Programs for Musculoskeletal Disorders]. United States of America: Bradford & Bigelow Printing, 2013.</ref>. Ice and heat have been suggested for pain management, but there is limited supporting evidence<ref name=":31" /> and no studies are proving<ref name=":31" />. | |||

'''Manual Therapy''' | |||

Myofascial restrictions of the joints below the hip, the hip itself and the lumbar spine can result in increased friction at the lateral hip and myofascial release is therefore indicated if a restriction is found<ref name=":31" />. Where joint restrictions exist at the lumbar spine, hip, knee and/or ankle, joint mobilisation can be done to improve mobility, thereby correcting hip biomechanics and reducing friction at the lateral hip<ref name=":31" />. | |||

'''Education''' | |||

Patients must be made aware of activities and positions that may further compress the gluteal tendons/bursa resulting in aggravated symptoms. Patients should avoid: | |||

* Climbing stairs<ref name=":21" /> | |||

* Hip adduction across the midline<ref name=":21" /><ref name=":8" /> | |||

* Walking uphill<ref name=":21" /> | |||

* Sitting with legs crossed<ref name=":21" /><ref name=":8" /> | |||

* Sitting with their knees higher than hips<ref name=":21" /> | |||

* Standing with more weight on one leg<ref name=":21" /><ref name=":8" /> | |||

* Side-lying positions<ref name=":21" />. If the patient struggles not to lie on their side, they should place pillows between their knees and ankles (modified side-lying) or lie on an eggshell overlay<ref name=":8" /> | |||

* Stretching of the ITB, gluteal muscles<ref name=":8" /> | |||

Advice regarding modification of exercise and activity should also be given<ref name=":8" />. This is further discussed in the therapeutic exercise paragraph below. | |||

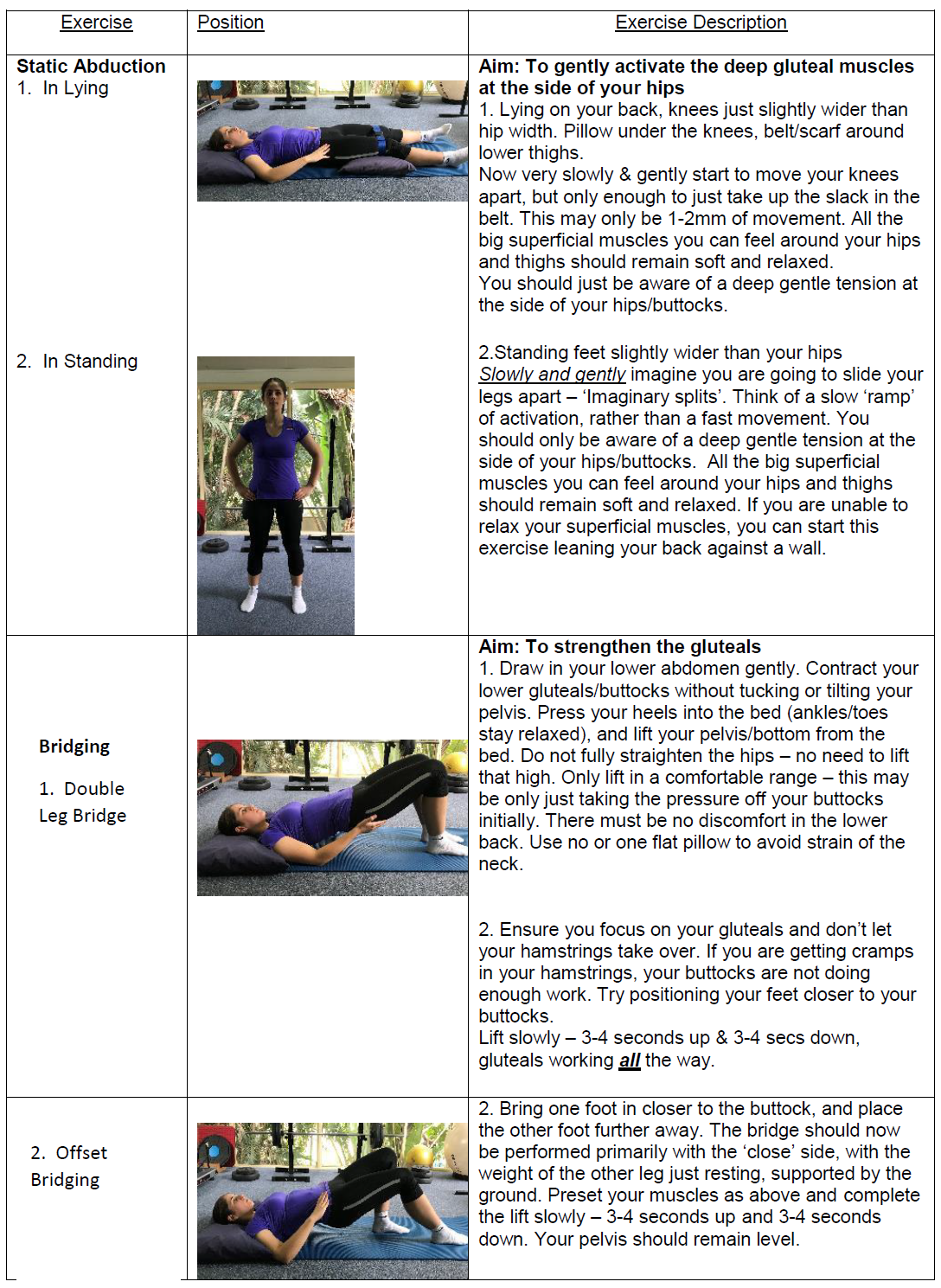

'''Therapeutic Exercise''' | |||

= | Sadly, there is little evidence of the effect of exercise on pain and dysfunction in GTPS<ref name=":21" />. | ||

<u>Isometric contractions (for gluteal tendinopathy)</u> | |||

Isometric contractions are now commonly used as they release cortical inhibition targeting both peripheral and central pain drivers. This cortical inhibition causes immediate pain reduction and for 45 minutes afterwards<ref name=":21" />. Cook (2020) reported that the analgesic effect can last for 4 to 8 hours after isometrics<ref name=":25" />. Isometric contractions must be heavy to effectively achieve pain relief in the tendon<ref name=":32">Rio E, Kidgell D, Purdam C, Gaida J, Moseley GL, Pearce AJ, Cook J.[https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/bjsports/49/19/1277.full.pdf Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy.] Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1277–1283.</ref><ref name=":25" />. The exact duration of the contraction is unknown, but 5 repetitions of 45 seconds is very effective<ris name=":32" /><ref name=":25" />. A rest period of 2 minutes must occur between each of the isometric contractions<ref name=":25" />. | |||

<u>Avoid Stretching</u> | |||

Stretching should be avoided when treating insertional tendinopathies as stretching, especially into adduction with the hip in flexion or extension increases the compression forces on the tendon<ref name=":8" />. | |||

<u>Exercise</u> | |||

Exercise is important in the management of all the possible causes of GTPS: | |||

* Gluteal tendinopathy requires gradual loading of the tendons to condition the tendon again so that it can tolerate load. More information about gluteal tendinopathy management can be found on the [[Gluteal Tendinopathy|Gluteal tendinopathy]] page. | |||

* Since Trochanteric bursitis is reported to most likely be secondary to gluteal tendinopathy, gradual loading is also indicated in these patients. | |||

* In patients with gluteal tendon repair, strengthening will be essential for optimal function and to improve the repaired tissue’s tensile strength. | |||

* Patients with external coxa saltans may be experiencing the problem due to muscle imbalances or increased muscle tension which will require modification of neuromuscular control. This is achieved through the correct strengthening and/or motor control exercise. | |||

Therapeutic exercise should be started early and consist of progressive tensile loading exercises in minimally adducted hip positions<ref name=":8" />. GMed has been found to activate better in weight-bearing positions compared to non-weight-bearing positions<ref name=":8" />. Exercise should be started at a moderate effort level and repetitions should be low. When night pain improves in patients with a gluteal tendinopathy, it is a good indicator that the tendon is responding to the exercise. If night pain increases it may indicate that the load was too high<ref name=":8" />. | |||

Strengthening should not only include the hip abductors but also the core and lumbopelvic stabilisers<ref name=":12" />. | |||

Ebert et al. (2018) provide a guideline for postoperative management for abductor tendon repair<ref name=":30" />. This guideline can be found in Table 2 below. | |||

Ganderton et al. (2018) compared the GLoBE programme to a sham exercise programme for management of GTPS. There was no added benefit of either the exercise program when added to education but the subjects in the GLoBE exercise group reported a better outcome than the sham exercise group. Ganderton et al. reported that this likely indicates sub-groups exist in GTPS<ref name=":21" />. The GLoBE exercise programme is outlined below in Table 3. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

! colspan="3" |Table 3: GLoBE exercise wiki tablename=":21" /><ref>Ausralian New Zealand Clinical Trials Regisry. Available from: https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=366865&isReview=true. Accessed 14 March 2020.</ref> | |||

|- | |||

|Phase | |||

|Exercise | |||

|Description | |||

|- | |||

| rowspan="3" |1 | |||

|Isometric hip hitch | |||

|Start with hip hitch with wall support. Progress to hip hitch without wall support, but with arm support. The unaffected limb should be hitched. Both knees should be kept straight. Begin with 2 x 15 second holds and progress to 4 x 40 second holds | |||

15-second squats on both legs | |||

|Double 40-second wall squats with hips in 20° external rotation. Progress to half wall squat. Begin with 1 set of 5 repetitions and increase to 4 sets of 5 repetitions. | |||

|- | |||

|Calf raises on both feet | |||

|Calf raises on both feet with arm support. Begin with 2 x 5 repetitions and increase to 2 x 10 repetitions. | |||

|- | |||

| rowspan="3" |2 | |||

|Hip hitch with toe taps | |||

|Hip Hitch with toe taps onto 7.5cm step. Progress to a 10cm step. Begin with 2 x 5 repetitions and increase to 2 x 15 repetitions. | |||

|- | |||

|Sit to stand | |||

|Sit to stand off a standard chair with arms crossed over the chest. Gradually decrease the height of the chair as tolerated. Begin with 1 x 5 repetitions and increase to 2 x 10 repetitions. | |||

|- | |||

|Calf raises with toe tap | |||

|Sustained calf raise with toe taps on the spot. Use a wall or chair for balance. Start with 2 x 5 repetitions and increase to 2 x 10 repetitions. | |||

|- | |||

| rowspan="3" |3 | |||

|Hip hitch with hip swing | |||

|The affected limb is the stance limb. Perform a sustained hip hitch on the affected limb. Complete hip swings 10° forwards and backwards with the contralateral leg. Begin with swings and then increase to 2 x 15 contralateral hip swings. | |||

|- | |||

|Sit to stand with split stance | |||

|Sit to stand off a standard chair with affected leg placed slightly behind the unaffected leg. Start with 2 x 5 repetitions and increase to 4 x 5 repetitions. | |||

|- | |||

|Single leg calf raises | |||

|Single leg calf raise with arm support. Start with 2 x 5 repetitions and increase to 4 x 5 repetitions. | |||

|- | |||

| rowspan="3" |4 | |||

|Single leg wall squat | |||

|2 x 5 repetitions | |||

|- | |||

|Step ups | |||

|2 x 10 repetitions. | |||

|- | |||

|Single leg calf raises with arm support | |||

|2 x 15 repetitions. | |||

|} | |||

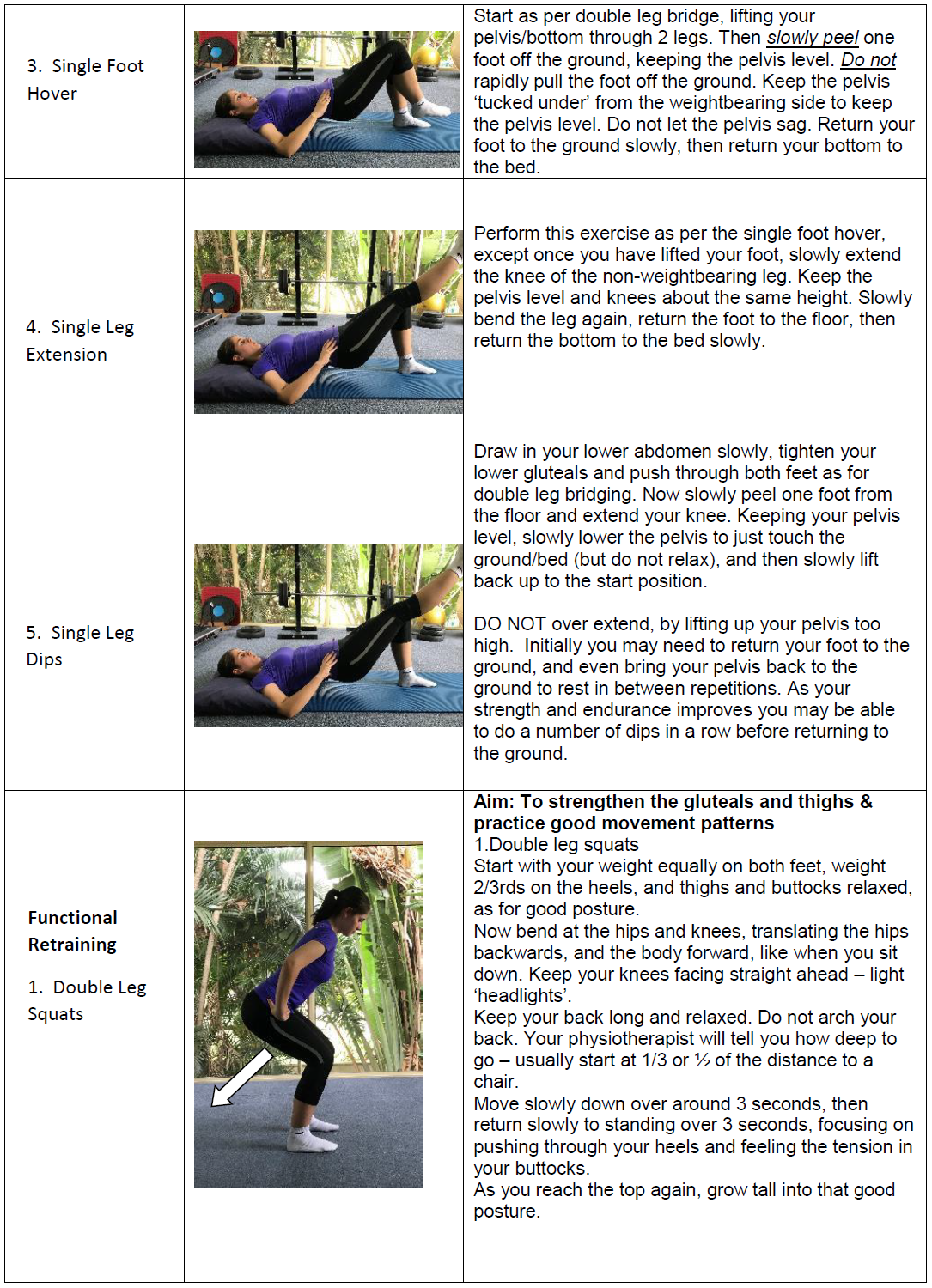

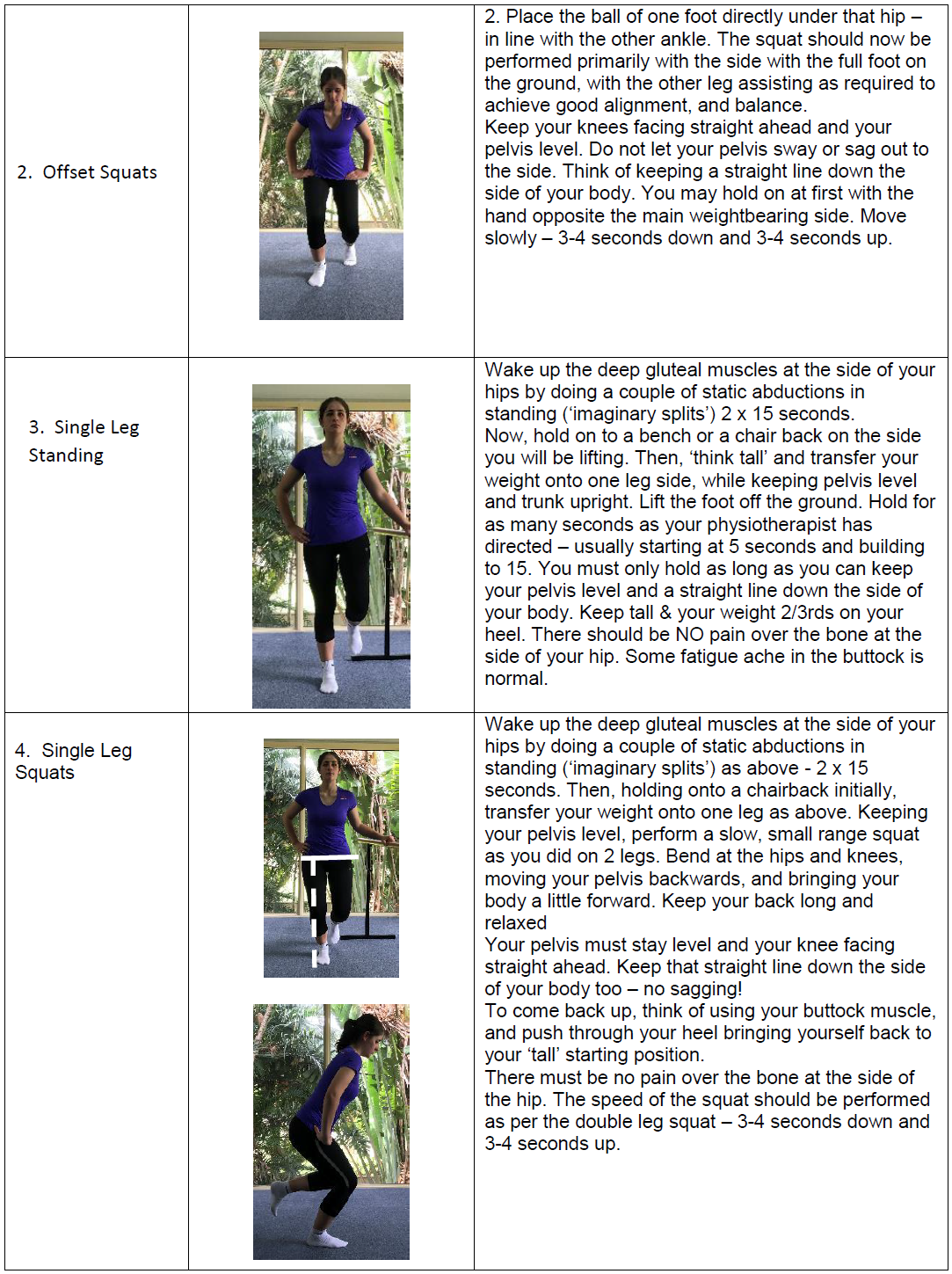

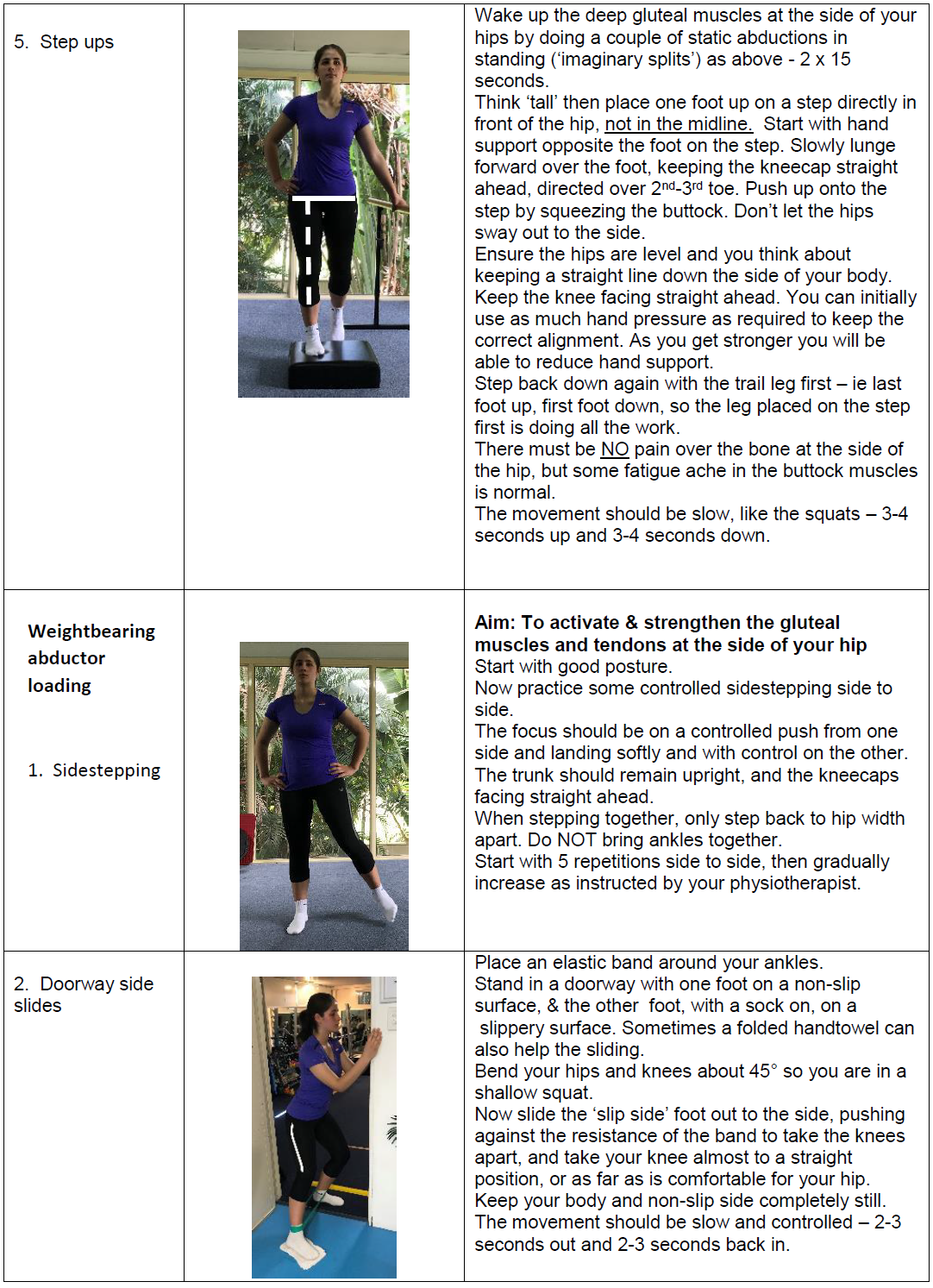

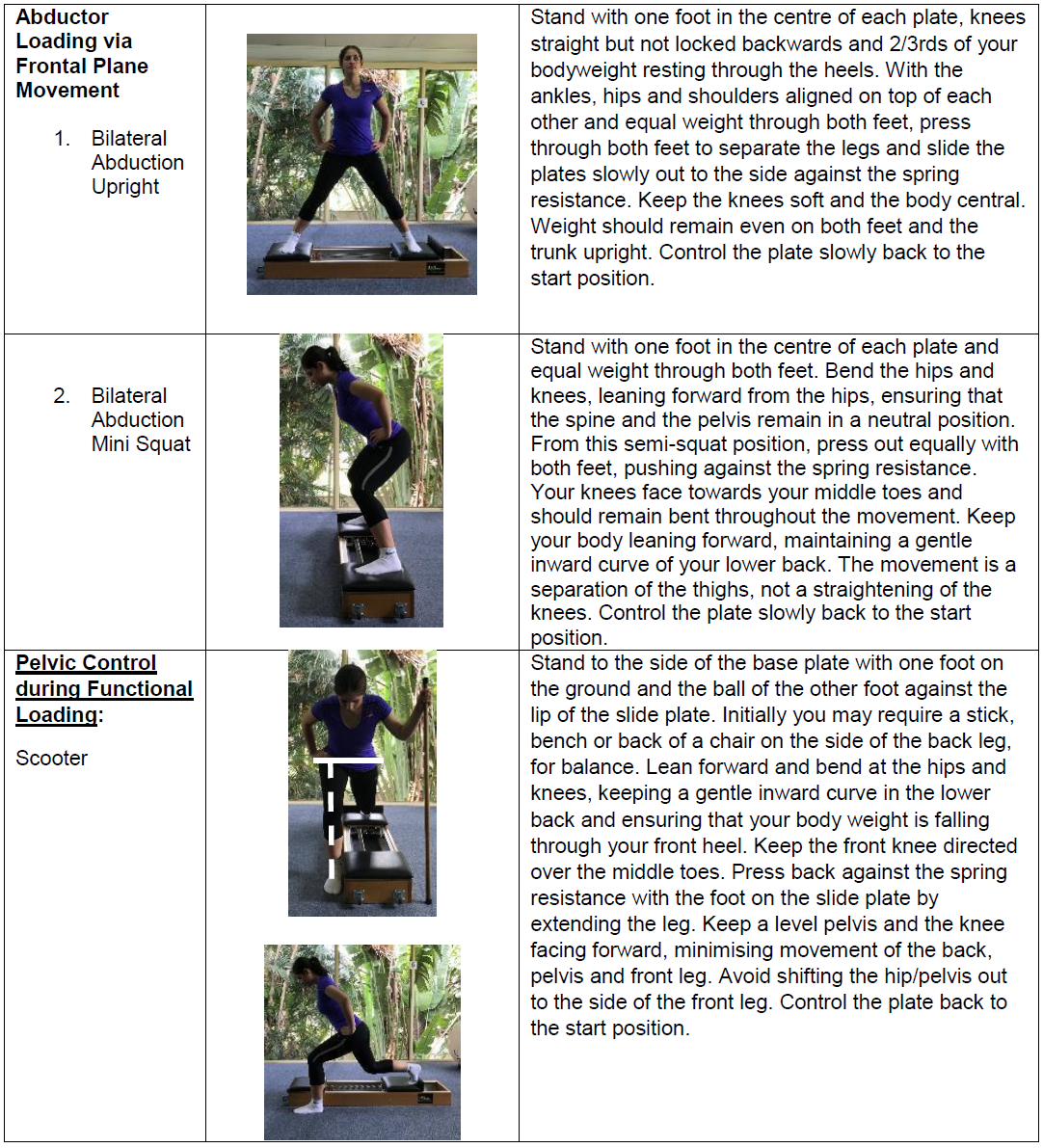

Mellor et al. (2018) found exercise plus education to be superior to corticosteroid injections and it remained that way at 52 weeks follow-up<ref name=":33">Mellor R, Bennell K, Grimaldi A, Nicolson P, Kasza J, Hodges P, et al. [https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/361/bmj.k1662.full.pdf Education plus exercise versus corticosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial.] BMJ. 2018;360:1-9.</ref>. This study showed that exercise plus education was even superior to corticosteroid injections in the first 8 weeks, showing that exercise plus education is effective from early on<ref name=":33" />. They made use of a progressive exercise programme that can be found below in the LEAP trial images p1 to p5.<ref name=":33" />. | |||

It is clear that strengthening of the hip abductors is an important component of GTPS management, but what exercise is most effective? Firstly, all prescribed exercise must patient-specific and should be determined by the phase of tissue healing, the patient’s tolerance of the exercise and/or the principles of progressive loading<ref name=":34">Ebert JR, Edwards PK, Fick DP, Janes GC. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/motriz/v25n3/1980-6574-motriz-25-03-e101983.pdf. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. 2017;26:418 -436.</ref>. A study published in 2017 assessed various exercises to determine their degree of GMed activation<ref name=":34" />. A short summary of the results is found below in Table 4. | |||

It is worth mentioning that the popular clam exercise was found by to produce negligible activation in the GMed (particularly the anterior and middle portions) by Ganderton et al. (2017)<ref name=":35">Ganderton C, Pizzari T, Cook J, Semciw A. [https://www.jospt.org/doi/10.2519/jospt.2017.7229?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed Gluteus Minimus and Gluteus Medius Muscle Activity During Common Rehabilitation Exercises in Healthy Postmenopausal Women]. JOSPT. 2017;47(12):914-922.</ref>. In this same study, the hip hitch was found to best activate the GMed and GMin<ref name=":35" />. | |||

[[File:LEAP study interventions.png|thumb|1489x1489px|LEAP trial p1 Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. Mellor R, Bennell K, Grimaldi A, Nicolson P, Kasza J, Hodges P, Wajswelner H, Vicenzino B. Education plus exercise versus corticosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2018;360:1-9. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.k1662 Published online: 2 May 2018 https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1662 | |||

|none]] | |||

[[File:LEAP study interventions p2.png|thumb|1500x1500px|LEAP trial p2 Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. Mellor R, Bennell K, Grimaldi A, Nicolson P, Kasza J, Hodges P, Wajswelner H, Vicenzino B. Education plus exercise versus corticosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2018;360:1-9. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.k1662 Published online: 2 May 2018 https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1662 | |||

|none]] | |||

[[File:LEAP study interventions p3.png|thumb|1449x1449px|LEAP trial p3 Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. Mellor R, Bennell K, Grimaldi A, Nicolson P, Kasza J, Hodges P, Wajswelner H, Vicenzino B. Education plus exercise versus corticosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2018;360:1-9. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.k1662 Published online: 2 May 2018 https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1662 | |||

|none]] | |||

[[File:LEAP study p4.png|left|thumb|1493x1493px|LEAP trial p4 Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. Mellor R, Bennell K, Grimaldi A, Nicolson P, Kasza J, Hodges P, Wajswelner H, Vicenzino B. Education plus exercise versus corticosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2018;360:1-9. https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1662 | |||

]] | |||

[[File:LEAP study interventions p5.png|left|thumb|1191x1191px|LEAP trial p5 Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. Mellor R, Bennell K, Grimaldi A, Nicolson P, Kasza J, Hodges P, Wajswelner H, Vicenzino B. Education plus exercise versus corticosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2018;360:1-9. https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1662 | |||

]] | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

| colspan="4" |Table 4: GMed exercises in order of degree of activation<ref name=":34" /> | |||

|- | |||

|Low | |||

|Moderate | |||

|Moderate to High | |||

|High to very High | |||

|- | |||

| | |||

* Bilateral supine bridge | |||

* Double limb free standing | |||

* Double limb wall/swiss ball assisted squat | |||

* Double limb free squat on a flat surface | |||

| | |||

* Any quadruped exercise including: | |||

** Straight leg hip extension (weak limb NWB) | |||

** Flexed knee hip extension (weak limb NWB or WB) | |||

* Standing hip abduction with the weak limb NWB | |||

* | |||

* Forward plane band walks, in a forward direction | |||

* Side lunge | |||

* Retro step | |||

* Lateral plane band walks with no hip rotation | |||

| | |||

* Unilateral supine bridge | |||

* Standing hip abduction with the weak limb WB | |||

* Hip/pelvic hitches | |||

* Side-lying hip abduction | |||

* Transverse lunge | |||

* Forward step-up | |||

* Lateral step-up | |||

| | |||

* Single leg dead-lift | |||

* Side-bridge on single leg | |||

* | |||

* | * Hip hitches with contralateral limb movement | ||

* Hip hitches on an unstable surface. “Weak” limb WB | |||

* Single leg squat on unstable surface | |||

* Lateral plane band walks with hip IR, flexed trunk and band around the feet | |||

* Side-lying hip abduction with hip in IR | |||

* Forward lunges | |||

* Hopping | |||

|- | |||

| colspan="4" |Abbreviations: NWB, non-weight-bearing; WB, weight-bearing; IR, internal rotation | |||

|} | |||

== | == Surgical Management == | ||

Surgery should only be done if conservative management has failed<ref name=":1" /> or when there is a significant tendon tear<ref name=":8" />. | |||

'''Bursectomy''' | |||

This intervention used to be carried out by open surgery, but now it is most commonly done arthroscopically. Fox et al. (2002) found that arthroscopic trochanteric bursectomy is a minimally invasive technique, that appears to be a safe and an effective approach for managing GTPS<ref>Bird PA, Oakley SP, Shnier R, Kirkham BW. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/1529-0131%28200109%2944%3A9%3C2138%3A%3AAID-ART367%3E3.0.CO%3B2-M Prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging and physical examination findings in patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome]. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology. 2001 Sep;44(9):2138-45.</ref><ref>Fox JL. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8511071_Early_results_of_endoscopic_trochanter_bursectomy The role of arthroscopic bursectomy in the treatment of trochanteric bursitis]. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2002 Sep 1;18(7):1-4.</ref>. In a more recent study by Mitchell et al. (2016) successful management of GTPS was achieved with endoscopic arthroscopic bursectomy together with an iliotibial band release<ref>Mitchell JJ, Chahla J, Vap AR, Menge TJ, Soares E, Frank JM, et al. [https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S2212628716300755?token=7E2B348D6166DE7BBE253F66BE89BA704C172BA26CCC5FE2AAE9B732502D4484B70BAFDF7BA844986883EFF8B6DD44CF Endoscopic trochanteric bursectomy and iliotibial band release for persistent trochanteric bursitis]. Arthroscopy techniques. 2016 Oct 1;5(5):e1185-9.</ref>.<br> | |||

{{#ev:youtube|IruDHmSnhQ0}} | |||

'''Iliotibial band surgical options''' | |||

Surgery is not the first choice of management but in cases where functional impairment is present, surgery can be done. There are three options in these patients: iliotibial tract (ITT) release, ITT bursectomy and lateral synovial recess resection<ref name=":14" />. Another study released in 2012 also found surgical ITT release and trochanteric bursectomy to be an effective and safe treatment<ref name=":27">Govaert LH, van Dijk CN, Zeegers AV, Albers GH. [https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S2212628712000308?token=9F79090358204CBF4F10CFAE61A386D5F4B9F11C75E0BD53C87F55E8A2D455288B7CBE3330AEEBBF78359BEFC02842A9 Endoscopic bursectomy and iliotibial tract release as a treatment for refractory greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a new endoscopic approach with early results.] Arthroscopy techniques. 2012 Dec 1;1(2):e161-4.</ref>. | |||

'''Reduction-osteotomy of the greater trochanter''' | |||

This is an option should bursectomy and ITT release fail. | |||

* Large incision of 7 to 10 cm<ref name=":27" /> | |||

* | * Highest rate of complications<ref name=":28">Koulischer S, Callewier A, Zorman D. [http://actaorthopaedica.be/assets/2500/02-Koulisher.pdf Management of greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a systematic review.] Acta Orthop Belg. 2017 Jun;83:205-14.</ref>. | ||

* During the procedure a 5 to 10mm slice of bone was removed deep to the greater trochanter and continued distally beyond the vastus ridge, GMed was left attached, fixation with two lag screws was done once transfer of the medial and distal trochanter was completed<ref name=":10" />. | |||

* | '''Reconstruction/Repair of the abductor tendon''' | ||

When MRI and clinical findings are consistent with a tendon tear, surgical repair is an option. Far better functional and clinical outcomes have been reported when a synthetic ligament is used during a procedure called augmented repair<ref>Ebert JR, Brogan K, Janes GC. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338755889_A_Prospective_2-Year_Clinical_Evaluation_of_Augmented_Hip_Abductor_Tendon_Repair A prospective 2-year clinical evaluation of augmented hip abductor tendon repair.] Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine. 2020 Jan 22;8(1):2325967119897881.</ref>. This particular outcome was found in a study where patients were reassessed 2 years after surgery. | |||

Ebert et al. (2018) published a postoperative management protocol for patients with abductor repairs, see ref<ref name=":30">Ebert JR, Bucher TA, Mullan CJ, Janes GC. [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.5301/hipint.5000525 Clinical and functional outcomes after augmented hip abductor tendon repair.] Hip International. 2018 Jan;28(1):74-83.</ref> | |||

==== | ==Take Home Message== | ||

* | * Conservative treatment is the gold standard for GTPS. | ||

* | * Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is often under-diagnosed. | ||

* Encourage physical therapy and activity modifications. | |||

* Cautious use of CSI - possible negative effect on the tendon in the long-term<ref name=":0" /> | |||

==== | ==References== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] | |||

[[Category:Hip]] | [[Category:Hip]] | ||

[[Category:Pain]] | [[Category:Pain]] | ||

| Line 254: | Line 400: | ||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | [[Category:Sports Medicine]] | ||

[[Category:Sports Injuries]] | [[Category:Sports Injuries]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:56, 18 May 2024

Original Editors - Kirianne Vander Velden as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel's Evidence-based Practice project

Top Contributors -Wendy Snyders, Kim Jackson, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Ahmed M Diab, Andrea Nees, WikiSysop and Rishika Babburu

Description[edit | edit source]

Lateral Hip pain is a common orthopaedic problem. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS), previously known as trochanteric bursitis, affects 1.8 per 1000 patients annually[1].

- GTPS is a clinical diagnosis of lateral hip pain and includes trochanteric bursitis associated with a tendinopathy[2][1]; gluteus medius (GMed)/minimus (GMin) tendinopathy[3][1][4]; tears of the gluteus medius or minimus tendons[5][6][7] and external coxa saltans[5][4].

- Patients complain of pain over the lateral aspect of the thigh that is exacerbated with prolonged sitting, climbing stairs, high impact physical activity, or lying over the affected area.

- The main bursae that are associated with GPTS are the gluteus minimus, subgluteus medius, and the subgluteus maximus.

- Previously, trochanteric bursitis was seen as the main pain source, but recent research indicates that the fluid within the bursa rather exists due to the gluteal tendinopathy and not because of primary inflammation in the bursa[1][2][8]. The most recent research indicates GMed and GMin tendinopathy as the most frequent cause of GTPS[9] [8][10][11]and managing the underlying tendinopathy should take priority[6].

The proposed clinical definition of GTPS:

“A history of lateral hip pain and no difficulty with manipulating shoes and socks together with clinical findings of pain reproduction on palpation of the greater trochanter and lateral pain reproduction with the FABER test[12].”

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The greater trochanter is situated on the proximal and lateral side of the femur, just distal to the hip joint and the neck of the femur.

- The tendons of the GMed, GMin, gluteus maximus (GMax) and the tensor fascia lata (TFL) attach onto this bony outgrowth (apophysis). The greater trochanter is seen to have 4 facets and the above-mentioned muscle attachments have been equated to the “rotator cuff of the hip”[13][7].

- The external iliac fossa is the origin of the GMed and GMin muscles (GMed attaching to the lateral and superolateral facets and the GMin inserting onto the anterior facet).

- The TFL lies over the GMed and GMin tendons and inserts onto the ITB[14].

On average, there are 6 bursae present around the lateral hip[15]. The locations of these bursae vary greatly - the size, location and number are not consistent.

- Four bursae are consistently present (multiple secondary bursa)[16].

- The three chief bursae at the hip include tsub gluteuseus maximus, sub gluteusteus minimus andsub gluteusuteus medius bursa[14].

- These bursae and the periosteum of the greater trochanter are innervated by a small branch of the femoral nerve[14][17].

Hip joint stability

- GMax muscle tensions the ITB via its ITB attachment and assists with improving the hip joint’s passive stability[18].

- ITB is also tensioned by the vastus lateralis and TFL and limits hip internal rotation and adduction passively[18].

- GMed prevents excessive hip adduction and is often seen as the primary stabilizer of the pelvis[18].

Hip joint innervation includes the rami articulares of the obturator nerve, the femoral nerve, sciatic nerve[19] and a branch of the femoral nerve that supplies the periosteum and bursae of the greater trochanter.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- Lateral hip pain affects 1.8 out of 1000 patients annually[1].

- Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is most prevalent between the fourth and sixth decades of life[5].

- Studies have shown that GTPS has a strong correlation with the female gender and obesity.[20]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Since GMed and GMin tendinopathy, tears of the GMed and GMin tendons, external coxa saltans and ITB abnormalities can all be possible causes of GTPS, the aetiology of each of these structures/pathologies need to be considered.

Tendinopathy aetiology:

- The exact mechanism is still unknown[5].

- Overuse[5]

- Mechanical overload[5][11]

- Incomplete or failed healing[5]

- Compression of the tendon at the enthesis [11]

- In people with weak hip abductors, particularly GMed, greater hip adduction is seen causing increased compression of the GMed and GMin tendons at the greater trochanter. With the increased adduction, the ITB exerts higher compressive forces on the gluteal tendons, amplifying the compression[6]. Hip positions in higher ranges of flexion may also increase the compression of the GMed and GMin tendons due to increased tension in the ITB, explaining why pain that occurs with prolonged sitting[11].

- Pelvic control in a single leg stance position - controlled 70% by the abductor muscles and the ITB tensioners (GMax, TFL and vastus lateralis) account for the remaining 30%[11]. People with gluteal tendinopathy tend to have GMed and GMin atrophy and TFL hypertrophy. Weakness and/or muscle bulk changes impact the balance of the abductor mechanism and increase the compression of the gluteal tendons[11].

- Women are more prone to GTPS because of pelvic biomechanics, different activity levels in the population and hormonal effects[14]. Females have a smaller insertion of the GMed tendon, resulting in a smaller area across which tensile load could be dissipated and a shorter moment arm, causing reduced mechanical efficiency[9].

- Increased fluid within the bursa is thought to be a consequence of the tendinopathy rather than it being due to inflammation of the bursa.[3].

Tears of the GMed and GMin tendons:

- A frequently missed cause of GTPS[21].

- Up to 25% of middle-aged women can have GMed tears. It is also found in up to 10% of middle-aged men[21].

- Tears can be acute but degenerative tears are far more common. It was thought that the GMed tendon was most frequently affected[7][21] but a study published in 2020 revealed that GMin tendons tears were more frequent than GMed tears[22]. GMed and GMin tears were associated with tendon and enthesis degeneration[22].

- Tears at the GMed tendon insertion can be complete, intrasubstance or partial, with partial tears occurring most frequently[7][21]. Complete tears of the GMed are associated with a coinciding GMin tear but MRI and ultrasound investigations very rarely identify the GMin tear[22].

- Most tears are found at the insertion of the anterior and middle portions of the GMed and GMin tendons.

Coxa saltans or Snapping Hip Syndrome:

- Presents in about 5% to 10% of the general population[23].

- Most commonly found in dancers and professional athletes, but can also occur due to physical trauma[23].

- It can be intra-articular or extra-articular[23] , with the extra-articular presentation being relevant to GTPS.

- Extra-articular coxa sultans most commonly involve the anterior part of GMax or the posterior ITB snapping over the greater trochanter, causing a catching or sensation of “giving way” and an inflammatory response in the trochanteric bursa.[23][24].

- There is often an imbalance between TFL and GMax activation in these patients[24].

- Patients can report a sensation of subluxation and worse pain with activities such as climbing stairs, hiking and running[23]. There are, however, patients who do not experience pain when it snaps[24].

Patients presenting with GTPS often have low back pain[5][9][25] or hip joint OA[5]. There is also a higher occurrence of GTPS in people with ITB syndrome and knee OA[26][14].

There is no clear evidence that a leg length discrepancy has any impact on a person developing GTPS[9][14].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

GTPS typically presents with lateral hip pain that may radiate down the lateral thigh and buttocks and occasionally to the lateral knee. It can be described as aching and intense at times of greater aggravation caused by passive, active and resisted hip abduction and external rotation[27]. It is often characterised by the ‘jump’ sign where palpation of the greater trochanter causes the patient to nearly jump off the bed[1].

The symptoms include:

- Tender lateral hip when palpated, especially near the greater trochanter[14][10][9][7][21]

- Pain with side-lying on the problematic side[14][10][9][28]

- Pain with weight-bearing activities such as walking, climbing stairs, standing and running[14][10][9][1][21][28][29]

- Pain may refer to the lateral thigh and knee[14][9][1][7]

- Pain with prolonged sitting[9][28]

- Pain with resisted abduction[7][21]

- Sitting with crossed legs increases pain[9]

- Pain can also occur when lying on the non-painful side if the painful hip falls into adduction

- Pain is usually episodic and will worsen over time with continued aggravation

- Weak hip abductors[29]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

To be able to treat GTPS correctly, accurate differential diagnosis is crucial[12]. Conditions that may mimic GTPS include the following:

- Hip OA[12][29][14][11][9]. Similar site of symptoms, aggravated by weight-bearing activity and weakness in hip abductors[29].

- Femoral head avascular necrosis (AV)[30][14]

- Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)[30][14][9]

- Lumbar spine referral or degenerative disease[30][11][9]

- Femoral-head stress fractures[14]

- Labral tears[14][9]

- Bony metastasis[9]

- Neck-of-femur fracture[9]

- Inflammatory disease such as RA[9]

Table 2 includes some important signs and symptoms of the differential diagnoses[9][14]:

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

There is no one specific test to confirm GTPS and the tests available lack validity when done in isolation. Diagnostic accuracy can however be improved when a combination of tests is used[1].

- The single leg stance test for 30 seconds has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 100% and al has very high sensitivity when pain is produced within 30 seconds of standing on the painful side[1],[14].

- Resisted hip medial rotation, lateral rotation and abduction can also be used to assess for GTPS. Resisted lateral rotation has the highest sensitivity (88%) and specificity (97.3%) when compared to resisted medial rotation and abduction[9]. The highest specificity is achieved when the test is done in 90° hip flexion[11].

- FADER, OBER and FABER - aim to increase the tensile load on the gluteal tendons[1].

- The ability to put one’s socks and shoes on without help will also help differentiate GTPS from OA, where the GTPS patient has no difficulty during activity [1].

- The “jump sign” carries a PPV of 83% so direct palpation of the greater trochanter helps to diagnose GTPS[1].

- The Trendelenburg sign is present in patients with GTPS and when used to assess for a GMed tear, it has a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 77%[14].

- If external coxa saltans is suspected - FABER, Ober test, Hula-Hoop test and active hip flexion followed by passive extension and abduction[31].

Imaging is only suggested in the following situations:

- When gluteal tears are suspected. Ultrasound or MRI can be used to confirm the diagnosis if suspected clinically[21][14]. Cook (2020) reports that ultrasound is the most accurate when assessing a tendon where MRI is helpful for differential diagnosis[32].

- When conservative treatment has failed[14][9].

- When diagnosis is unclear[9][14].

Above is a diagnostic flow chart created by Speers and Bhogal (2017) for the 3 most common causes of lateral hip pain[1].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- VISA-G - GTPS-specific outcome measure[33]

- HOOS - Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

- HHS - Harris Hip Score

- iHOT - International Hip Outcome Tool

Examination[edit | edit source]

GTPS is a clinical diagnosis which means the diagnosis is based on the medical history as well as the signs and symptoms. The assessment should include the following:

- A good subjective assessment to gather the necessary information regarding the signs and symptoms.

- Hip joint assessment

- Lumbar spine - this needs to be excluded as a possible cause of the pain.

- Special tests. These can be used to help confirm or negate the suspected diagnosis of GTPS. In 2017, Ganderton et al. validated the following tests for GTPS: FABER, resisted external de-rotation test, greater trochanter palpation and resisted abduction[34] (Click on the link to each test for more detailed information and/or a video regarding each test).

Trendelenburg Test: This is a quick test for assessing hip abductor muscle function and it can also be used to help determine if a tear is present in the hip abductors. A drop of the pelvis on the contralateral side of the stance leg indicates weakness of the stance leg's hip abductors and results in a positive test. Test administration is demonstrated here.

FABER Test: FABER is the acronym for flexion, abduction, and external rotation. It is very helpful in confirming GTPS[12] and it assists with differentiating between hip OA and GTPS[1].

Noble Test: This is used to verify Iliotibial tightness and helps to distinguish iliotibial tightness from other common causes of lateral knee pain, such as lateral collateral ligament strain, bicipital or popliteal tendinopathy, knee OA and lateral meniscal pathology[35]. Test administration is demonstrated here.

'Modified Ober’s Test ': This test and its modification are used to assess the TFL and ITB. The test is positive if the thigh does not go further than 10 degrees of adduction.

Renne’s Test: This test is used to assess ITB syndrome and can be done alone or in conjunction with the Noble Test.

'secondsecond ) Single leg stance test: The person being tested must stand, unassisted, on one leg with their eyes open and one finger on a wall. As soon as the person’s foot is lifted off the floor, the 30 seconds start. A positive test for patients with GTPS is lateral hip by 30 seconds. Grimaldi and Fearon (2015) suggest holding the position the until reproduction of symptoms[9].

ipz4Jjw Resisted external de-rotation test and modified external de-rotation test: The patient lies in supine and the examiner then passively flexes the hip to 90° with external rotation. The hip should be in neutral abduction/adduction. Slightly reduce the external rotation to decrease the compression of the tendon. The patient then actively rotates their leg to neutral against the therapist’s resistance. The modification is the same, but done in full hip adduction.[34]

Resisted abduction test: The examiner passively abducts the testing-limb to 45° abduction with the patient in side-lying or supine. The patient must then maintain this position against the examiner’s resistance. The resistance must be applied 1cm superior to the lateral malleolus[34]. This test has a 73% sensitivity and 87% specificity for GMed pathology[36].

Resisted internal rotation: This test has a 92% sensitivity, 85% specificity and 88% accuracy for diagnosing GMed tears . To perform the test, place the problematic limb into 90° hip and knee flexion with 10° hip external rotation while the patient is supine. While the examiner provides resistance to the movement, the patient must perform active hip internal rotation. The test is positive if the patient experiences pain and/or weakness.[36]

Diagnostic test clusters: Combination of palpation with resisted hip abduction in either abduction or adduction position can be useful in both ruling in or out GTPS. However, a 30-second single-leg stance may help in confirming a positive diagnosis.

Management[edit | edit source]

The initial approach to treat Greater trochanteric pain syndrome includes a range of conservative interventions such as physiotherapy, local corticosteroid injection, PRP injection, shockwave therapy (SWT), activity modification, pain-relief and anti-inflammatory medication and weight reduction.

- Most are resolved with conservative measures, with success rates of over 90%. For the majority of the cases, GTPS is self-limiting[20].

Non-Surgical Intervention

Non-surgical treatment options include the following:

- Physiotherapy, which includes manual therapy and therapeutic exercise

- Low energy extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT)

- Corticosteroid injection is effective in the short-term only[37] (3 to 4 months[11]) and is advised for bursitis rather than tendinopathy[14]. It is more effective to inject the greater trochanteric bursa than the subgluteus medius bursa[38].

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Exercise is promoted from early in treatment for tendinopathy and the main goals should include[1]:

- Load management

- Reduction of compressive forces

- Strengthening of the gluteal muscles and

- Management of any co-morbidities

See comprehensive exercise treatment regimes further below

Therapeutic Modalities

- ESWT was found to be more effective than corticosteroid injections and multimodal therapy at a 1-year follow-up. The long-term 1-year of ESWT is however controversial[37]. A study that combined exercise and ESWT found that this approach was superior to corticosteroid injection for pain relief at 15 months follow-up[14].

- Dry-needling is a commonly-used intervention in commonly used A study published in 2017 compared dry-needling to corticosteroid injections for pain relief in GTPS and found that corticosteroid injections did not offer greater pain relief or to dry-needling. There was also no difference in function improvement between the two groups. Based on this, dry needling may be a viable option for pain relief in GTPS[39].

- Other modalities like TENS, cross-frictions and low-level laser have not been assessed properly for GTPS[40]. Ice and heat have been suggested for pain management, but there is limited supporting evidence[40] and no studies are proving[40].

Manual Therapy

Myofascial restrictions of the joints below the hip, the hip itself and the lumbar spine can result in increased friction at the lateral hip and myofascial release is therefore indicated if a restriction is found[40]. Where joint restrictions exist at the lumbar spine, hip, knee and/or ankle, joint mobilisation can be done to improve mobility, thereby correcting hip biomechanics and reducing friction at the lateral hip[40].

Education

Patients must be made aware of activities and positions that may further compress the gluteal tendons/bursa resulting in aggravated symptoms. Patients should avoid:

- Climbing stairs[28]

- Hip adduction across the midline[28][9]

- Walking uphill[28]

- Sitting with legs crossed[28][9]

- Sitting with their knees higher than hips[28]

- Standing with more weight on one leg[28][9]

- Side-lying positions[28]. If the patient struggles not to lie on their side, they should place pillows between their knees and ankles (modified side-lying) or lie on an eggshell overlay[9]

- Stretching of the ITB, gluteal muscles[9]

Advice regarding modification of exercise and activity should also be given[9]. This is further discussed in the therapeutic exercise paragraph below.

Therapeutic Exercise

Sadly, there is little evidence of the effect of exercise on pain and dysfunction in GTPS[28].

Isometric contractions (for gluteal tendinopathy)

Isometric contractions are now commonly used as they release cortical inhibition targeting both peripheral and central pain drivers. This cortical inhibition causes immediate pain reduction and for 45 minutes afterwards[28]. Cook (2020) reported that the analgesic effect can last for 4 to 8 hours after isometrics[32]. Isometric contractions must be heavy to effectively achieve pain relief in the tendon[41][32]. The exact duration of the contraction is unknown, but 5 repetitions of 45 seconds is very effective<ris name=":32" />[32]. A rest period of 2 minutes must occur between each of the isometric contractions[32].

Avoid Stretching

Stretching should be avoided when treating insertional tendinopathies as stretching, especially into adduction with the hip in flexion or extension increases the compression forces on the tendon[9].

Exercise

Exercise is important in the management of all the possible causes of GTPS: