Meningitis: Difference between revisions

Karen Wilson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "[[Edema" to "[[Oedema") |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

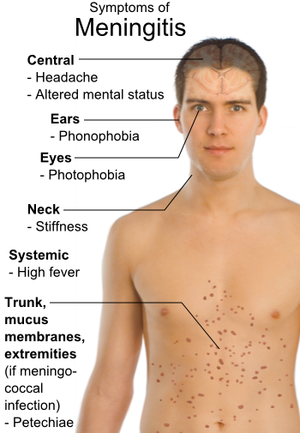

[[File:Symptoms of Meningitis.png|right|frameless]] | |||

Meningitis | |||

* An [[Infectious Disease|infectious disease]] of the central nervous system that causes [[Inflammation Acute and Chronic|inflammation]] of the meningeal [[Introduction to Neuroanatomy|membranes]] (involving all three layers) surrounding the [[Brain Anatomy|brain]] and [[Spinal cord anatomy|spinal cord]].<ref name="p1">1. Goodman C, Fuller K. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier, 2009.</ref> | |||

* Before the era of [[antibiotics]], the condition was universally fatal. Nevertheless, even with great innovations in healthcare, the condition still carries a mortality rate of close to 25%<ref name=":0">Hersi K, Kondamudi NP. 2020 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459360/ Meningitis.]Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459360/ (last accessed 28.11.2020)</ref>. | |||

* The disease can be caused by many different pathogens including [[Bacterial Infections|bacteria]], fungi or viruses, but the highest global burden is seen with bacterial meningitis.<ref>WHO Meningitis Available from:https://www.who.int/health-topics/meningitis#tab=tab_1 (accessed 28.11.2020)</ref> | |||

* Despite breakthroughs in diagnosis, treatment, and [[Vaccines|vaccination]], in 2015, there were 8.7 million reported cases of meningitis worldwide, with 379,000 subsequent deaths. | |||

* The first case of meningitis associated with [[Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)|COVID 19]] was detected in early 2020. A preliminary report warned that SARS-CoV-2 could have neuroinvasive potential because some patients present with meningitis symptoms (for example, headache, nausea, vomiting).<ref>Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, Ueno M, Sakata H, Kondo K, Myose N, Nakao A. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971220301958 A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020 Apr 3].Available from:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971220301958 (last accessed 29.11.2020)</ref> | |||

Meningitis is | == Etiology == | ||

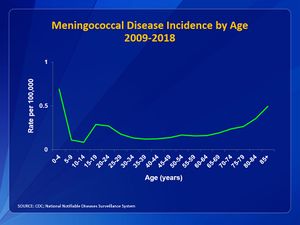

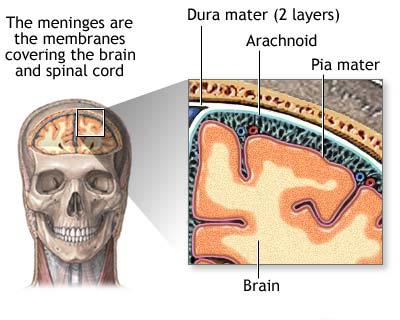

[[File:Meningococcal-graph-2015.jpg|right|frameless]]Meningitis is defined as inflammation of the meninges. The meninges are the three membranes (the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater) that line the vertebral canal and skull enclosing the brain and spinal cord ([[encephalitis]] is inflammation of the brain itself). | |||

Meningitis can be caused by infectious and non-infectious processes ([[Autoimmune Disorders|autoimmune disorders]], cancer/[[Paraneoplastic Syndrome|paraneoplastic]] syndromes, drug reactions). | |||

The infectious etiologic agents of meningitis include [[Bacterial Infections|bacteria]], [[Viral Infections|viruses]], [[Fungal Diseases|fungi]], and less commonly [[Parasitic Infections|parasites]].<ref>Hersi K, Gonzalez FJ, Kondamudi NP. Meningitis. [Updated 2021 Feb 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: <nowiki>https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459360/</nowiki></ref> | |||

Risk factors for meningitis include: | |||

*Chronic medical disorders ([[Chronic Kidney Disease|renal failure]], [[diabetes]], adrenal insufficiency, [[Cystic Fibrosis|cystic fibrosis]]); Extremes of age; Undervaccination; [[Immunocompromised Client|Immunosuppressed]] states (iatrogenic, transplant recipients, congenital immunodeficiencies, AIDS); Living in crowded conditions; Exposures: Travel to endemic areas (Southwestern U.S. for cocci; Northeastern U.S. for Lyme disease); [[Zoonotic Diseases|Vectors]] (mosquitoes, ticks); [[Alcoholism|Alcohol use disorder]]; Presence of ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt; Bacterial endocarditis; Malignancy; Dural defects; IV drug use; [[Sickle Cell Anemia|Sickle cell anemia]]; Splenectomy<ref name=":0" />; sinusitis, mastoiditis, and otitis.<ref name="p1" /> | |||

Meningococcal meningitis is of particular importance due to its potential to cause large epidemics. Bacteria are transmitted from person-to-person through droplets of respiratory or throat secretions from carriers.<ref name=":1">World Health Organization. Meningococcal meningitis. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/meningococcal-meningitis (accessed 30 March 2021).</ref> The disease can affect anyone of any age, but mainly affects babies, preschool children and young people. Untreated meningococcal meningitis can be fatal in up to 50% of cases and may result in brain damage, hearing loss or disability in 10% to 20% of survivors.<ref name=":1" /> While vaccines against meningococcal disease have been available for more than 40 years, to date no universal vaccine against meningococcal disease exists<ref>WHO Meningitis Available from:https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/meningitis (last accessed 28.11.2020)</ref>. | |||

== | == Epidemiology == | ||

[[File:Map-africa.jpg|thumb]] | |||

[[File:Meninges diagram.jpg|right|frameless|400x400px]] | |||

The incidence of meningitis is 2 of 6 per 10,000 adults per year in developed countries and is up to ten times higher in less-developed countries. <ref name="p6">Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.</ref> <ref>Meningitis Belt [Internet]. 2017 [cited 5 March 2017]. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2016/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/meningococcal-disease</ref> | |||

* In the United States, the annual incidence of bacterial meningitis is approximately 1.38 cases/100,000 population with a case fatality rate of 14.3%. | |||

* The highest incidence of meningitis worldwide is in an area of sub-Saharan Africa dubbed “the meningitis belt” stretching from Ethiopia to Senegal. | |||

* The prevalence of meningitis has greatly decreased over the last fifteen years due to the development of [[vaccines]].<ref name="p1" /> | |||

Pathogens: | |||

# Most common bacterial causes of meningitis in the United States are: Streptococcus pneumoniae (incidence in 2010: 0.3/100,000); group B Streptococcus; Neisseria meningitidis (incidence in 2010: 0.123/100,000); Haemophilus influenzae (incidence in 2010: 0.058/100,000); Listeria monocytogenes (video below of bacterial meningitis){{#ev:youtube|xQC6L8M6XfU}}<ref>Armando Hasudungan (Bacterial) Meningitis Pathophysiology. Available fromhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xQC6L8M6XfU&feature=emb_logo</ref> | |||

# The most common viral agents of meningitis are non-polio enteroviruses (group b coxsackievirus and echovirus). Other viral causes: mumps, Parechovirus, Herpesviruses (including [[Epstein-Barr Virus|Epstein Barr virus also known as Mononucleosis]], Herpes simplex virus, and Varicella-zoster virus), measles, influenza, and arboviruses (West Nile, La Crosse, Powassan, Jamestown Canyon) | |||

# Fungal meningitis typically is associated with an immunocompromised host (HIV/AIDS, chronic corticosteroid therapy, and patients with cancer). Fungi causing meningitis include: Cryptococcus neoformans; Coccidioides immitis; [[Aspergillosis|Aspergillus]]; Candida; Mucormycosis (more common in patients with diabetes mellitus and transplant recipients; direct extension of sinus infection)<ref name=":0" /><ref>Meningococcal Graph [Internet]. 2017 [cited 5 March 2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/surveillance/</ref> | |||

== Pathophysiology == | |||

Meningitis typically occurs through two routes: | |||

[[ | # Hematogenous seeding: Bacteria colonize the nasopharynx and enter the bloodstream after the mucosal invasion. Upon making their way to the subarachnoid space, the bacteria cross the blood-brain barrier, causing a direct inflammatory and [[Immune System|immune-mediated reaction]]. | ||

# Direct contiguous spread: Organisms can enter the cerebrospinal fluid ([[CSF Cerebrospinal Fluid|CSF]]) via neighboring anatomic structures (otitis media, sinusitis), foreign objects (medical devices, penetrating trauma), or during operative procedures. | |||

Viruses can penetrate the central nervous system (CNS) via retrograde transmission along neuronal pathways or by hematogenous seeding.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | == Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | ||

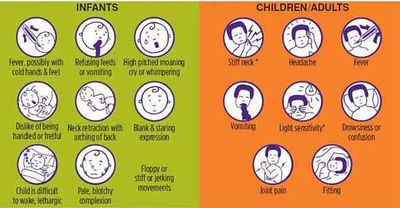

[[Image:Meningitis-symptoms2.jpg|right|frameless|400x400px]]Headache, fever, vomiting, and rigidity of the neck are the most common symptoms that present with the onset of meningitis.<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p2">Porter RS, Kaplan JL. The Merck manual of diagnosis and therapy. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; 2011. </ref><ref name="neuro">Aminoff M, Greenberg D, Simon R. Clinical Neurology. 6th ed. New York, NY: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill, 2005.</ref> Early symptoms include nausea, drowsiness, and confusion. Pain in the posterior thigh or lumbar region may also be noted.<ref name="p1" /> Later symptoms can include seizures, photophobia, and rapid breathing rate. In addition, a rash on the skin, scanty petechial (red or purple non-blanching macules smaller than 2mm in diameter), or a purpuric (larger than 2mm) appears on approximately 80-90% of individuals with bacterial meningitis.<ref name="neuro" /> <ref>Paul N, Bowe C, Morrow G. Bacterial Meningitis. WIN. 2016;24(8):47-49.</ref> <ref>Watkins J. Recognising the signs and symptoms of meningitis. British Journal of School Nursing. 2012;7(10):481-483.</ref> | |||

Meningitis causes inflammation of the meningeal membranes; as a result, nerve roots may endure tension as they pass through these inflamed membranes. Passive ROM of the neck into flexion will gradually become painful and limited. Also, neck extension and rotation may be painful as well, but not to the extent of flexion. In severe cases, [[Brudzinski’s Sign|Brudzinki’s sign]] ( caused by passive neck flexion producing flexion of the hips or knees) or [[Kernig's Sign|Kernig’s sign]] presents.<ref>Meningitis control in countries of the African meningitis belt, 2015. World Health Organization [Internet]. 2015 [cited 9 March 2017];16:209-216. Available from:http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.libproxy.bellarmine.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=f38a50a1-dce1-4c95-8af1-4b603ccaee02%40sessionmgr102&vid=9&hid=104</ref> In cases when meningitis is not treated immediately (especially bacterial meningitis), the parenchyma within the brain may be involved. As a result, individuals may present with lethargy, vomiting, seizures, papilledema, confusion, coma, focal deficits, and cranial nerve palsies. | |||

Meningitis causes inflammation of the meningeal membranes; as a result nerve roots may endure tension as they pass through these inflamed membranes. Passive ROM of the neck into flexion will gradually become painful and limited. Also, neck extension and rotation may be painful as well, | |||

<ref>Neisseri Meningitidis. Brudzinski’s sign. http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/s2008/bingen_sama/neck.jpg (accessed 6 April 2010)</ref> <ref>National Library of Medicine. Kernig’s sign. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/images/ency/fullsize/19077.jpg (accessed 6 April 2010)</ref> | |||

{{#ev:youtube|gHhwl6on5sQ|400}}<ref>Meningitis Tests [Internet]. 2017 [cited 11 April 2017]. Available from: https://youtu.be/gHhwl6on5sQ</ref> | |||

=== | == Treatment/Management == | ||

[[Antibiotics]] and supportive care are critical in all cases of bacterial meningitis. | |||

Managing the airway, maintaining oxygenation, giving sufficient intravenous fluids while providing fever control are parts of the foundation of meningitis management. | |||

* | * The type of antibiotic is based on the presumed organism causing the infection. The clinician must take into account patient demographics and past medical history in order to provide the best antimicrobial coverage. | ||

'''[[Corticosteroid Medication|Steroid]] Therapy''': There is insufficient evidence to support the widespread use of steroids in bacterial meningitis. | |||

'''Increased Intracranial Pressure''': If the patient develops clinical signs of increased intracranial pressure (altered mental status, neurologic deficits, non-reactive pupils, bradycardia), interventions to maintain cerebral perfusion include: | |||

* | * Elevating the head of the bed to 30 degrees | ||

* | * Inducing mild hyperventilation in the intubated patient | ||

* Osmotic [[Diuretics in the Treatment of Hypertension|diuretics]] such as 25% mannitol or 3% saline | |||

'''Chemoprophylaxis''': Indicated for close contacts of a patient diagnosed with N. meningitidis and H. influenzae type B meningitis. Close contacts include housemates, significant others, those who have shared utensils, and health care providers in proximity to secretions (providing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, intubating without a facemask).<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== | == Diagnostic Tests == | ||

# Meningitis is diagnosed through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, which includes white blood cell count, glucose, protein, culture, and in some cases, polymerase chain reaction (PCR). CSF is obtained via a lumbar puncture (LP), and the opening pressure can be measured. | |||

# Additional testing should be performed tailored on suspected etiology: Viral: Multiplex and specific PCRs; Fungal: CSF fungal culture, India ink stain for Cryptococcus; Mycobacterial: CSF Acid-fast bacilli smear and culture; Syphilis: CSF VDRL; Lyme disease: CSF burgdorferi antibody<ref name=":0" /> | |||

=== | == Complications == | ||

The median risk of sequelae post-discharge was 19.9% (2010 metaanalysis). The most common organism isolated was H. influenzae, followed by S. pneumoniae. The most common sequelae were hearing loss (6%), followed by behavioral (2.6%) and cognitive difficulties (2.2%), motor deficit (2.3%), seizure disorder (1.6%) and visual impairment (0.9%). | |||

Other complications include: | |||

* | * Increased intracranial pressure from cerebral [[Oedema Assessment|edema]] caused by increased intracellular fluid in the brain. Several factors are involved in the development of cerebral edema: increased in blood-brain barrier permeability, cytotoxicity from cytokines, immune cells, and bacteria. | ||

* [[Hydrocephalus]] | |||

* Cerebrovascular complications | |||

* | * [[Overview of Traumatic Brain Injury|Focal neurologic deficits]]<ref name=":0" /> | ||

<ref name="p0">Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.</ref><ref name="p2" /><ref name="neuro" /> | <ref name="p0">Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.</ref><ref name="p2" /><ref name="neuro" /> | ||

== Physical Therapy Management == | == Physical Therapy Management == | ||

According to the American Physical Therapy Association's ''Guide to Physical Therapist Practice'' infectious disorders of the central nervous system fall under the following preferred practice patterns; 5D: Impaired Motor Function and Sensory Integrity Associated with Nonprogressive Disorders of the Central Nervous System- Acquired in Adulthood or Adolescence and 5I: Impaired Arousal, Range of Motion, and Motor Control Associated with Coma, Near Coma, or Vegetative State. | |||

According to the American Physical Therapy Association's ''Guide to Physical Therapist Practice'' infectious disorders of the central nervous system fall under the following preferred practice patterns; 5D: Impaired Motor Function and Sensory Integrity Associated with Nonprogressive Disorders of the Central Nervous System- Acquired in Adulthood or Adolescence and 5I: Impaired Arousal, Range of Motion, and Motor Control Associated with Coma, Near Coma, or Vegetative State. | |||

Typically physical therapy treatment is initiated in the intensive care unit. While initiating a plan of care, it is crucial to keep in mind a patient’s chart information or contraindications to therapy such as intracranial pressure, cerebral perfusion pressure, and other lab values that determine rehabilitation guidelines. Meningitis may present with similar symptoms to brain injuries, neurological complications, immunological deficiency, vascular compromise, and additional secondary impairments. | Typically physical therapy treatment is initiated in the intensive care unit. While initiating a plan of care, it is crucial to keep in mind a patient’s chart information or contraindications to therapy such as intracranial pressure, cerebral perfusion pressure, and other lab values that determine rehabilitation guidelines. Meningitis may present with similar symptoms to brain injuries, neurological complications, immunological deficiency, vascular compromise, and additional secondary impairments. | ||

Additionally understanding the various stages of consciousness or behavioral changes a patient with secondary complications may go through can guide the approach to treatment. The therapist should create an environment that would ease the patient’s hypersensitivity to sensory input such as light or sound thus creating a structured environment to eliminate behavioral outbursts. Close monitoring of the vital signs will allow the therapist to | Additionally understanding the various stages of consciousness or behavioral changes a patient with secondary complications may go through can guide the approach to treatment. The therapist should create an environment that would ease the patient’s hypersensitivity to sensory input such as light or sound thus creating a structured environment to eliminate behavioral outbursts. Close monitoring of the vital signs will allow the therapist to gauge the patient's receptiveness to therapy. The therapist should be familiar with the [http://www.strokecenter.org/Trials/scales/glasgow_coma.pdf Glasgow Coma Scale] and monitor the patient’s progression through the levels of consciousness. | ||

Proper positioning and range of motion exercise should be | Proper positioning and range of motion exercise should be initiated as soon as safely possible in the acute phase. Proper positioning with pillows and towels will protect the skin integrity and prevention of contractures. Maintaining mobility of the trunk and neck are important to sustain functional mobility. The earlier therapy is initiated with a patient, the chances of secondary impairments are decreased allowing for a better prognosis. | ||

A primary key component to treating a patient recovering from bacterial meningitis is proper education not only to the patient | A primary key component to treating a patient recovering from bacterial meningitis is proper education not only to the patient but to the family and caregivers as well. Providing the patient and family with education on the disease, stages of the disease, secondary complications, warning signs, and resources can encourage the patient and family to become more involved in the treatment. It is very important to educate on the effects of different systemic involvement and how the timeline of recovery may vary.<ref name="p1" /> | ||

== Differential Diagnosis == | == Differential Diagnosis == | ||

* [[Stroke]] | |||

* Subdural hematoma | |||

* [[Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH)|Subarachnoid hemorrhage]] | |||

* [[Oncology|Metastatic]] brain disease | |||

* Brain abscess (might coexist with meningitis)<ref name=":0" /> | |||

===== Case Reports ===== | |||

== Case Reports == | |||

1. Case presentation of a 70-year-old male who presented with increasing memory disorders and a 7-month history of left buttock pain, right transient temporal head pain, and right conjunctival injection who was later diagnosed with enteroviral meningoencephalitis: [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2637149/pdf/nihms89780.pdf/?tool=pmcentrez A Case of Enteroviral Meningoencephalitis Presenting as Rapidly Progressive Dementia].<ref>Valcour V, Haman A, Cornes S, Lawall C, Parsa A, Glaser C, et al. A case of enteroviral meningoencephalitis presenting as rapidly progressive dementia. Nature Clinical Practice. Neurology [serial on the Internet]. (2008, July), [cited April 8, 2010]; 4(7): 399-403. Available from: MEDLINE.</ref> | |||

2. A 46-year-old male presented to the ER with a 7-week history of headache, fatigue, and nausea as well as altered mental status over the last 2 days. Past medical history revealed an otherwise healthy individual. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2359896/pdf/nihms%2D44761.pdf/?tool=pmcentrez Cryptococcal meningitis was diagnosed. Not Your “Typical Patient”: Cryptococcal Meningitis in an Immunocompetent Patient].<ref>Thompson H. Not your "typical patient": cryptococcal meningitis in an immunocompetent patient. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing [serial on the Internet]. (2005, June), [cited April 8, 2010]; 37(3): 144-148. Available from: CINAHL with Full Text.</ref> | |||

3. Otis was noted as a comorbidity for meningitis. Case report following a 77-year-old man who was admitted into the hospital for difficulty speaking, ear pain, fever, and altered mental status proceeding fall several days earlier. Diagnosis of bacterial meningitis was given. [http://proquest.umi.com.libproxy.bellarmine.edu/pqdweb?did=1379484931&sid=1&Fmt=4&clientId=1870&RQT=309&VName=PQD Case 34-2007; A 77-Year_old Man with Ear Pain, Difficulty Speaking, and Altered Mental Status.]<ref>Samuels M, Gonzalez R, Kim A, Stemmer-Rachamimov A. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 34-2007. A 77-year-old man with ear pain, difficulty speaking, and altered mental status. The New England Journal Of Medicine [serial on the Internet]. (2007, Nov 8), [cited April 8, 2010]; 357(19): 1957-1965. Available from: MEDLINE.</ref> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Bellarmine_Student_Project]] | |||

[[Category:Acute Care]] | [[Category:Acute Care]] | ||

[[Category:Communicable Diseases]] | |||

[[Category:Global Health]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:45, 3 August 2022

Original Editors - Iris Partin from Bellarmine University's; Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Cathy Agapay, Iris Partin, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, George Prudden, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Dave Pariser, Kristin Paris, Joseph Ayotunde Aderonmu, Oyemi Sillo, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Elaine Lonnemann, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Wendy Walker, Nupur Smit Shah, Scott Buxton, Karen Wilson and Claire Knott

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Meningitis

- An infectious disease of the central nervous system that causes inflammation of the meningeal membranes (involving all three layers) surrounding the brain and spinal cord.[1]

- Before the era of antibiotics, the condition was universally fatal. Nevertheless, even with great innovations in healthcare, the condition still carries a mortality rate of close to 25%[2].

- The disease can be caused by many different pathogens including bacteria, fungi or viruses, but the highest global burden is seen with bacterial meningitis.[3]

- Despite breakthroughs in diagnosis, treatment, and vaccination, in 2015, there were 8.7 million reported cases of meningitis worldwide, with 379,000 subsequent deaths.

- The first case of meningitis associated with COVID 19 was detected in early 2020. A preliminary report warned that SARS-CoV-2 could have neuroinvasive potential because some patients present with meningitis symptoms (for example, headache, nausea, vomiting).[4]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Meningitis is defined as inflammation of the meninges. The meninges are the three membranes (the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater) that line the vertebral canal and skull enclosing the brain and spinal cord (encephalitis is inflammation of the brain itself).

Meningitis can be caused by infectious and non-infectious processes (autoimmune disorders, cancer/paraneoplastic syndromes, drug reactions).

The infectious etiologic agents of meningitis include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and less commonly parasites.[5]

Risk factors for meningitis include:

- Chronic medical disorders (renal failure, diabetes, adrenal insufficiency, cystic fibrosis); Extremes of age; Undervaccination; Immunosuppressed states (iatrogenic, transplant recipients, congenital immunodeficiencies, AIDS); Living in crowded conditions; Exposures: Travel to endemic areas (Southwestern U.S. for cocci; Northeastern U.S. for Lyme disease); Vectors (mosquitoes, ticks); Alcohol use disorder; Presence of ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt; Bacterial endocarditis; Malignancy; Dural defects; IV drug use; Sickle cell anemia; Splenectomy[2]; sinusitis, mastoiditis, and otitis.[1]

Meningococcal meningitis is of particular importance due to its potential to cause large epidemics. Bacteria are transmitted from person-to-person through droplets of respiratory or throat secretions from carriers.[6] The disease can affect anyone of any age, but mainly affects babies, preschool children and young people. Untreated meningococcal meningitis can be fatal in up to 50% of cases and may result in brain damage, hearing loss or disability in 10% to 20% of survivors.[6] While vaccines against meningococcal disease have been available for more than 40 years, to date no universal vaccine against meningococcal disease exists[7].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The incidence of meningitis is 2 of 6 per 10,000 adults per year in developed countries and is up to ten times higher in less-developed countries. [8] [9]

- In the United States, the annual incidence of bacterial meningitis is approximately 1.38 cases/100,000 population with a case fatality rate of 14.3%.

- The highest incidence of meningitis worldwide is in an area of sub-Saharan Africa dubbed “the meningitis belt” stretching from Ethiopia to Senegal.

- The prevalence of meningitis has greatly decreased over the last fifteen years due to the development of vaccines.[1]

Pathogens:

- Most common bacterial causes of meningitis in the United States are: Streptococcus pneumoniae (incidence in 2010: 0.3/100,000); group B Streptococcus; Neisseria meningitidis (incidence in 2010: 0.123/100,000); Haemophilus influenzae (incidence in 2010: 0.058/100,000); Listeria monocytogenes (video below of bacterial meningitis)[10]

- The most common viral agents of meningitis are non-polio enteroviruses (group b coxsackievirus and echovirus). Other viral causes: mumps, Parechovirus, Herpesviruses (including Epstein Barr virus also known as Mononucleosis, Herpes simplex virus, and Varicella-zoster virus), measles, influenza, and arboviruses (West Nile, La Crosse, Powassan, Jamestown Canyon)

- Fungal meningitis typically is associated with an immunocompromised host (HIV/AIDS, chronic corticosteroid therapy, and patients with cancer). Fungi causing meningitis include: Cryptococcus neoformans; Coccidioides immitis; Aspergillus; Candida; Mucormycosis (more common in patients with diabetes mellitus and transplant recipients; direct extension of sinus infection)[2][11]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Meningitis typically occurs through two routes:

- Hematogenous seeding: Bacteria colonize the nasopharynx and enter the bloodstream after the mucosal invasion. Upon making their way to the subarachnoid space, the bacteria cross the blood-brain barrier, causing a direct inflammatory and immune-mediated reaction.

- Direct contiguous spread: Organisms can enter the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) via neighboring anatomic structures (otitis media, sinusitis), foreign objects (medical devices, penetrating trauma), or during operative procedures.

Viruses can penetrate the central nervous system (CNS) via retrograde transmission along neuronal pathways or by hematogenous seeding.[2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Headache, fever, vomiting, and rigidity of the neck are the most common symptoms that present with the onset of meningitis.[1][12][13] Early symptoms include nausea, drowsiness, and confusion. Pain in the posterior thigh or lumbar region may also be noted.[1] Later symptoms can include seizures, photophobia, and rapid breathing rate. In addition, a rash on the skin, scanty petechial (red or purple non-blanching macules smaller than 2mm in diameter), or a purpuric (larger than 2mm) appears on approximately 80-90% of individuals with bacterial meningitis.[13] [14] [15]

Meningitis causes inflammation of the meningeal membranes; as a result, nerve roots may endure tension as they pass through these inflamed membranes. Passive ROM of the neck into flexion will gradually become painful and limited. Also, neck extension and rotation may be painful as well, but not to the extent of flexion. In severe cases, Brudzinki’s sign ( caused by passive neck flexion producing flexion of the hips or knees) or Kernig’s sign presents.[16] In cases when meningitis is not treated immediately (especially bacterial meningitis), the parenchyma within the brain may be involved. As a result, individuals may present with lethargy, vomiting, seizures, papilledema, confusion, coma, focal deficits, and cranial nerve palsies.

Treatment/Management[edit | edit source]

Antibiotics and supportive care are critical in all cases of bacterial meningitis.

Managing the airway, maintaining oxygenation, giving sufficient intravenous fluids while providing fever control are parts of the foundation of meningitis management.

- The type of antibiotic is based on the presumed organism causing the infection. The clinician must take into account patient demographics and past medical history in order to provide the best antimicrobial coverage.

Steroid Therapy: There is insufficient evidence to support the widespread use of steroids in bacterial meningitis.

Increased Intracranial Pressure: If the patient develops clinical signs of increased intracranial pressure (altered mental status, neurologic deficits, non-reactive pupils, bradycardia), interventions to maintain cerebral perfusion include:

- Elevating the head of the bed to 30 degrees

- Inducing mild hyperventilation in the intubated patient

- Osmotic diuretics such as 25% mannitol or 3% saline

Chemoprophylaxis: Indicated for close contacts of a patient diagnosed with N. meningitidis and H. influenzae type B meningitis. Close contacts include housemates, significant others, those who have shared utensils, and health care providers in proximity to secretions (providing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, intubating without a facemask).[2]

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

- Meningitis is diagnosed through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, which includes white blood cell count, glucose, protein, culture, and in some cases, polymerase chain reaction (PCR). CSF is obtained via a lumbar puncture (LP), and the opening pressure can be measured.

- Additional testing should be performed tailored on suspected etiology: Viral: Multiplex and specific PCRs; Fungal: CSF fungal culture, India ink stain for Cryptococcus; Mycobacterial: CSF Acid-fast bacilli smear and culture; Syphilis: CSF VDRL; Lyme disease: CSF burgdorferi antibody[2]

Complications[edit | edit source]

The median risk of sequelae post-discharge was 19.9% (2010 metaanalysis). The most common organism isolated was H. influenzae, followed by S. pneumoniae. The most common sequelae were hearing loss (6%), followed by behavioral (2.6%) and cognitive difficulties (2.2%), motor deficit (2.3%), seizure disorder (1.6%) and visual impairment (0.9%).

Other complications include:

- Increased intracranial pressure from cerebral edema caused by increased intracellular fluid in the brain. Several factors are involved in the development of cerebral edema: increased in blood-brain barrier permeability, cytotoxicity from cytokines, immune cells, and bacteria.

- Hydrocephalus

- Cerebrovascular complications

- Focal neurologic deficits[2]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

According to the American Physical Therapy Association's Guide to Physical Therapist Practice infectious disorders of the central nervous system fall under the following preferred practice patterns; 5D: Impaired Motor Function and Sensory Integrity Associated with Nonprogressive Disorders of the Central Nervous System- Acquired in Adulthood or Adolescence and 5I: Impaired Arousal, Range of Motion, and Motor Control Associated with Coma, Near Coma, or Vegetative State.

Typically physical therapy treatment is initiated in the intensive care unit. While initiating a plan of care, it is crucial to keep in mind a patient’s chart information or contraindications to therapy such as intracranial pressure, cerebral perfusion pressure, and other lab values that determine rehabilitation guidelines. Meningitis may present with similar symptoms to brain injuries, neurological complications, immunological deficiency, vascular compromise, and additional secondary impairments.

Additionally understanding the various stages of consciousness or behavioral changes a patient with secondary complications may go through can guide the approach to treatment. The therapist should create an environment that would ease the patient’s hypersensitivity to sensory input such as light or sound thus creating a structured environment to eliminate behavioral outbursts. Close monitoring of the vital signs will allow the therapist to gauge the patient's receptiveness to therapy. The therapist should be familiar with the Glasgow Coma Scale and monitor the patient’s progression through the levels of consciousness.

Proper positioning and range of motion exercise should be initiated as soon as safely possible in the acute phase. Proper positioning with pillows and towels will protect the skin integrity and prevention of contractures. Maintaining mobility of the trunk and neck are important to sustain functional mobility. The earlier therapy is initiated with a patient, the chances of secondary impairments are decreased allowing for a better prognosis.

A primary key component to treating a patient recovering from bacterial meningitis is proper education not only to the patient but to the family and caregivers as well. Providing the patient and family with education on the disease, stages of the disease, secondary complications, warning signs, and resources can encourage the patient and family to become more involved in the treatment. It is very important to educate on the effects of different systemic involvement and how the timeline of recovery may vary.[1]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Stroke

- Subdural hematoma

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Metastatic brain disease

- Brain abscess (might coexist with meningitis)[2]

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

1. Case presentation of a 70-year-old male who presented with increasing memory disorders and a 7-month history of left buttock pain, right transient temporal head pain, and right conjunctival injection who was later diagnosed with enteroviral meningoencephalitis: A Case of Enteroviral Meningoencephalitis Presenting as Rapidly Progressive Dementia.[21]

2. A 46-year-old male presented to the ER with a 7-week history of headache, fatigue, and nausea as well as altered mental status over the last 2 days. Past medical history revealed an otherwise healthy individual. Cryptococcal meningitis was diagnosed. Not Your “Typical Patient”: Cryptococcal Meningitis in an Immunocompetent Patient.[22]

3. Otis was noted as a comorbidity for meningitis. Case report following a 77-year-old man who was admitted into the hospital for difficulty speaking, ear pain, fever, and altered mental status proceeding fall several days earlier. Diagnosis of bacterial meningitis was given. Case 34-2007; A 77-Year_old Man with Ear Pain, Difficulty Speaking, and Altered Mental Status.[23]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1. Goodman C, Fuller K. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Hersi K, Kondamudi NP. 2020 Meningitis.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459360/ (last accessed 28.11.2020)

- ↑ WHO Meningitis Available from:https://www.who.int/health-topics/meningitis#tab=tab_1 (accessed 28.11.2020)

- ↑ Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, Ueno M, Sakata H, Kondo K, Myose N, Nakao A. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020 Apr 3.Available from:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971220301958 (last accessed 29.11.2020)

- ↑ Hersi K, Gonzalez FJ, Kondamudi NP. Meningitis. [Updated 2021 Feb 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459360/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 World Health Organization. Meningococcal meningitis. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/meningococcal-meningitis (accessed 30 March 2021).

- ↑ WHO Meningitis Available from:https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/meningitis (last accessed 28.11.2020)

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Meningitis Belt [Internet]. 2017 [cited 5 March 2017]. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2016/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/meningococcal-disease

- ↑ Armando Hasudungan (Bacterial) Meningitis Pathophysiology. Available fromhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xQC6L8M6XfU&feature=emb_logo

- ↑ Meningococcal Graph [Internet]. 2017 [cited 5 March 2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/surveillance/

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Porter RS, Kaplan JL. The Merck manual of diagnosis and therapy. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; 2011.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Aminoff M, Greenberg D, Simon R. Clinical Neurology. 6th ed. New York, NY: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill, 2005.

- ↑ Paul N, Bowe C, Morrow G. Bacterial Meningitis. WIN. 2016;24(8):47-49.

- ↑ Watkins J. Recognising the signs and symptoms of meningitis. British Journal of School Nursing. 2012;7(10):481-483.

- ↑ Meningitis control in countries of the African meningitis belt, 2015. World Health Organization [Internet]. 2015 [cited 9 March 2017];16:209-216. Available from:http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.libproxy.bellarmine.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=f38a50a1-dce1-4c95-8af1-4b603ccaee02%40sessionmgr102&vid=9&hid=104

- ↑ Neisseri Meningitidis. Brudzinski’s sign. http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/s2008/bingen_sama/neck.jpg (accessed 6 April 2010)

- ↑ National Library of Medicine. Kernig’s sign. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/images/ency/fullsize/19077.jpg (accessed 6 April 2010)

- ↑ Meningitis Tests [Internet]. 2017 [cited 11 April 2017]. Available from: https://youtu.be/gHhwl6on5sQ

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- ↑ Valcour V, Haman A, Cornes S, Lawall C, Parsa A, Glaser C, et al. A case of enteroviral meningoencephalitis presenting as rapidly progressive dementia. Nature Clinical Practice. Neurology [serial on the Internet]. (2008, July), [cited April 8, 2010]; 4(7): 399-403. Available from: MEDLINE.

- ↑ Thompson H. Not your "typical patient": cryptococcal meningitis in an immunocompetent patient. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing [serial on the Internet]. (2005, June), [cited April 8, 2010]; 37(3): 144-148. Available from: CINAHL with Full Text.

- ↑ Samuels M, Gonzalez R, Kim A, Stemmer-Rachamimov A. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 34-2007. A 77-year-old man with ear pain, difficulty speaking, and altered mental status. The New England Journal Of Medicine [serial on the Internet]. (2007, Nov 8), [cited April 8, 2010]; 357(19): 1957-1965. Available from: MEDLINE.