Thoracolumbar Fascia

Original Editor - Wendy Walker

Lead Editors - Wendy Walker, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Sehriban Ozmen, WikiSysop, Naomi O'Reilly and Bruno Serra

Description[edit | edit source]

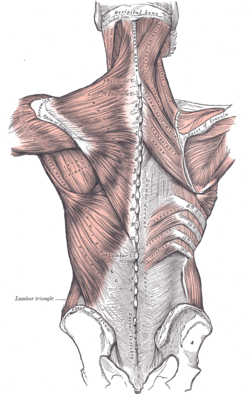

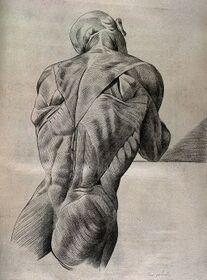

The thoracolumbar fascia (TLF) is a girdling structure consisting of several aponeurotic and fascial layers that separate the paraspinal muscles from the muscles of the posterior abdominal wall.

Most developed in the lumbar region, it consists of multiple layers of crosshatched collagen fibres that cover the back muscles in the lower thoracic and lumbar area before passing through these muscles to attach to the sacrum. Above, it is continuous with a similar investing layer on the back of the neck—the nuchal fascia. [1][2]

The TLF is a critical part of a myofascial girdle that surrounds the lower portion of the torso, playing an important role in posture, load transfer and respiration. [1] The fascial system is a "fibrous collagenous tissue which is part of a body-wide tensional force transmission system".[3]

The TLF contains nociceptive free nerve endings and has been proposed to represent a possible source of idiopathic low back pain. In addition, chemical stimulation of the TLF nociceptors has been shown to elicit severe and particularly long-lasting sensitization processes. [4]

Injury to the thoracolumbar fascia usually manifests as tightness, spasticity and increased tone in the lower thoracic spine and lumbar spine / paraspinal regions causing severe pains. [5]

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The TLF ( or lumbodorsal fascia) is a deep investing membrane that covers the deep muscles of the back of the trunk.

In the thoracic region, the TLF forms a thin covering for the extensor muscles of the vertebral column. Medially, it is attached to the spines of the thoracic vertebrae, and laterally it is attached to the ribs, near their angles[6].

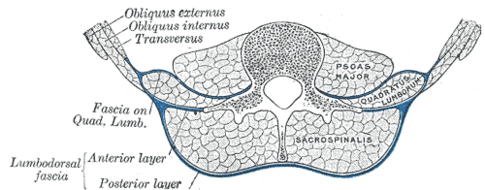

In the lumbar region the TLF is divided into three layers (previously described as two layers, anterior and posterior):

- The posterior layer: is attached to the spinous processes of the lumbar and sacral vertebrae and the supraspinal ligament;

- The middle layer (previously anterior layer): attached, medially, to the tips of the transverse processes lumbar vertebrae and the intertransverse ligaments; below, to the iliolumbar ligament; above, to the lumbocostal ligament.

- The anterior layer (fascia Covering the Quadratus Lumborum) is a thin layer: attached, medially, to the bases of the transverse processes lumbar vertebrae; below, to the iliolumbar ligament; above, to the apex and lower border of the last rib. Laterally, it blends with the lumbodorsal fascia, the anterior layer of which intervenes between the Quadratus lumborum and the erector spinae muscles.

The three layers unite at the lateral margin of the paraspinal muscles, to form the tendon of origin of the Transversus abdominis. The aponeurosis of origin of the Serratus posterior inferior and the Latissimus dorsi are intimately blended with the TLF.[7]

The nuchal fascia (fascia covering the splenius and semispinalis capitis muscles of the neck as a part of the cervical fascia) is a continuation of the posterior layer of the TLF.[8]

The video below gives a good functional view of the TLF

Function[edit | edit source]

The unyielding character of the deep fascia enables it to serve as a means of containing and separating groups of muscles into relatively well-defined spaces called ‘compartments’. The deep fascia integrates these compartments and transmits load between them.

Numerous trunk and extremity muscles with a wide range of thicknesses and geometries insert into the connective tissue planes of the TLF and can play a role in modulating the tension and stiffness of this structure

The TLF, being important in the myofascial girdle that surrounds the lower portion of the torso, plays an important role in stabilisation and load transfer [9].

- The connection that the thoracolumbar fascia has with the posterior ligaments of the lumbar spine allows it to assist in supporting the vertebral column when it is flexed by developing fascial tension that helps control the abdominal wall[10].

- When the spine is placed in full flexion, the TLF increases in length from the neutral position by about 30%[11]. The expansion in length of this tissue is accomplished by a tightening in width. This deformation places ‘strain-energy’ into the tissue, which should be recoverable in the form of reduced muscle work when the spine moves back in extension

Load Transfer Role Limbs[edit | edit source]

Vleeming et al[12] have highlighted the importance of the TLF in integrating the activity of muscles (traditionally regarded as belonging to the lower limb, upper limb, spine or pelvis and whose action is thus often considered in that territory alone).

They argue that a common attachment to the TLF means that the latter has an important role in integrating load transfer between different regions.

In particular, they propose that the gluteus maximus and latissimus dorsi (two of the largest muscles of the body) contribute to co-ordinating the contralateral pendulum-like motions of the upper and lower limbs that characterise eg running or swimming[12].

They suggest doing this via their shared attachment to the posterior layer of the TLF.

Clinical Significance[edit | edit source]

The existing research suggests that the lumbodorsal fascia may play a role in causing low back pain (LBP) through nociceptive mechanisms. [4]

The first quantitative study on abnormal connective tissue structure in the lumbar region in people with chronic LBP of more than 12 months duration[13], using ultrasound, found increased thickness and echogenicity (thought to be a result of the presence of fat) of the perimuscular connective tissue structure in the lumbar region in the LBP group compared to the No-LBP group. Abnormal connective tissue structure may be a predisposing factor for LBP, or a consequence of injury and/or changes in movement patterns occurring as a result of chronic pain. A potentially important consequence of injury may be fibrosis and adhesions, causing loss of independent motion of adjacent connective tissue layers which could further restrict body movements. [13]

The below video shows an injury to TLF on MRI and US images ...excuse the push for plasma-guided injections at the end.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

For people with chronic low back pain, myofascial release of the lumbar region has a higher and moderate level of evidence of pain improvement compared to other osteopathy techniques. [15]

A study suggests that myofascial release and Graston techniques can be applied to TLF as they showed similar results such as increased lumbar range of motion and proprioception in the acute period of young adults. [16]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Willard FH, Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Danneels L, Schleip R. The thoracolumbar fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerations. Journal of anatomy. 2012 Dec;221(6):507-36.Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3512278/ (accessed 14.2.2022)

- ↑ Askinglot What is thoracolumbar fascia?Available: https://askinglot.com/what-is-thoracolumbar-fascia(accessed 14.2.2022)

- ↑ George T, De Jesus O. Physiology, Fascia.2021 Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568725/(accessed 14.2.2022)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wilke J, Schleip R, Klingler W, Stecco C. The lumbodorsal fascia as a potential source of low back pain: a narrative review. BioMed research international. 2017 May 11;2017.

- ↑ Kenhub Thoracolumbar fascia Available:https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/thoracolumbar-fascia (accessed 14.2.2022)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Education Institute Throacaolumbar fascia Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TS2lT_gFlus (last accessed 25.5.2019)

- ↑ IMAIOS TLF Available: https://www.imaios.com/en/e-Anatomy/Anatomical-Parts/Thoracolumbar-fascia (accessed 14.2.2022)

- ↑ IMAIOS Nuchal fascia Available:https://www.imaios.com/en/e-Anatomy/Anatomical-Parts/Nuchal-fascia (accessed 14.2.2022)

- ↑ The thoracolumbar fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerations. Willard FH, Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Danneels L, Schleip R.J Anat. 2012 Dec;221(6):507-36

- ↑ Determination of safe load. Gracovetsky S Br J Ind Med. 1986 Feb; 43(2): 120–133

- ↑ Gracovetsky S, Farfan H F, Lamy C. The mechanism of the lumbar spine. Spine 1981; 6: 249-62.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 The posterior layer of the thoracolumbar fascia. Its function in load transfer from spine to legs. Vleeming A, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Stoeckart R, van Wingerden JP, Snijders CJ. LRSpine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Apr 1; 20(7):753-8.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Langevin HM, Stevens-Tuttle D, Fox JR, Badger GJ, Bouffard NA, Krag MH: Ultrasound evidence of altered lumbar connective tissue structure in human subjects with chronic low back pain. In Fascia research ii. Edited by Huijing PA, Hollander AP, Findley T, Schleip R. Elsevier, Munich; 2009

- ↑ Chris Centeno TLF injury causing back pain Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AqMQrXttxVE (last accessed 25.5.2019)

- ↑ Dal Farra F, Risio RG, Vismara L, Bergna A. Effectiveness of osteopathic interventions in chronic non-specific low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2021 Jan 1;56:102616.

- ↑ GÜNEŞ, Musa; YANA, Metehan. Acute effects of thoracolumbar fascia release techniques on range of motion, proprioception, and muscular endurance in healthy young adults. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2023, 35: 145-150.