Dementia: Difference between revisions

m (added research from The Latest Specialities) |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Definition == | == Definition == | ||

Dementia | Dementia describes an overall decline in [[memory]] and other thinking skills severe enough to reduce a person's ability to perform everyday activities. It is characterized by the progressive and persistent [[Cognitive Impairments|deterioration of cognitive function]]. Patients with dementia have problems with cognition, behaviour, and functional [[Activities of Daily Living|activities of everyday life.]] In addition, affected patients have memory loss and lack of insight into their problems.<ref name=":6">Emmady PD, Tadi P, Del Pozo E. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557444/ Dementia] (Nursing). Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557444/ (accessed 20.9.2021)</ref> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|HobxLbPhrMc}}<ref>AlzheimersResearch UK What is dementia? Alzheimer's Research UK Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HobxLbPhrMc&feature=emb_logo</ref> | {{#ev:youtube|HobxLbPhrMc}}<ref>AlzheimersResearch UK What is dementia? Alzheimer's Research UK Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HobxLbPhrMc&feature=emb_logo</ref> | ||

== | == Pathophysiology == | ||

The pathophysiology of dementia is not understood completely. Most types of dementia, except vascular dementia, are caused by the accumulation of native proteins in the brain. | |||

* [[Alzheimers disease|Alzheimer Disease]] (AD) is characterized by widespread atrophy of the [[Cerebral Cortex|cortex]] and deposition of amyloid plaques and tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein in the [[Neurone|neurons]] which contribute to their degeneration. A genetic basis has been established for both early and late-onset AD. Certain factors like depression, traumatic head injury, cardiovascular disease, family history of dementia, smoking, and the presence of APOE e4 allele have been shown to increase the risk of development of AD. | |||

* | * [[Lewy Body Disease|Lewy Body Dementia]] is characterized by the intracellular accumulation of Lewy bodies (which are insoluble aggregates of alpha-synuclein) in the neurons, mainly in the cortex. | ||

* Cells in this region are normally first to be damaged in [[Alzheimer's Disease | * [[Frontotemporal Dementia]] is characterized by the deposition of ubiquitinated TDP-43 and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins in the [[Frontal Lobe|frontal]] and [[Temporal Lobe|temporal lobe]]<nowiki/>s leading to dementia, early personality, and behavioral changes, and [[aphasia]]. | ||

* [[Vascular Dementia|Vascular dementia]] is caused by ischemic injury to the [[Brain Anatomy|brain]] (e.g., [[stroke]]), leading to permanent neuronal death.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

</ref> | <br> | ||

The [https://www.physio-pedia.com/Introduction_to_Neuroanatomy#Limbic_System hippocampus] though is often involved and contributes to the well-known symptoms of memory loss. Cells in this region are normally first to be damaged in [[Alzheimer's Disease]]<ref>Maruszak A, Thuret S. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3978283/ Why looking at the whole hippocampus is not enough—a critical role for anteroposterior axis, subfield and activation analyses to enhance predictive value of hippocampal changes for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis.] Front Cell Neurosci. 2014; 8: 95. </ref>, resulting in the common symptom of memory loss. Changes in hippocampal volume (a reduction) are seen with common patterns of aging but are exacerbated in Alzheimer's. <ref>den Heijer T, van der Lign F, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, van der Lugt A, Krestin GP, Niessen WJ, Breteler MMB. [https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/133/4/1163/312623 A 10-year follow-up of hippocampal volume on magnetic resonance imaging in early dementia and cognitive decline]. Brain. 2010. 133; 4: 1163–1172. | |||

</ref> | |||

== Epidemiology == | |||

Dementia affects approximately 47 million people worldwide and is projected to increase to 75 million in 2030 and | Dementia affects approximately 47 million people worldwide and is projected to increase to 75 million in 2030 and 152·8 (130·8–175·9) million by 2050.<ref>Nichols E, Steinmetz JD, Vollset SE, Fukutaki K, Chalek J, Abd-Allah F, Abdoli A, Abualhasan A, Abu-Gharbieh E, Akram TT, Al Hamad H. [https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(21)00249-8/fulltext Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.] The Lancet Public Health. 2022 Feb 1;7(2):e105-25.Available:https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(21)00249-8/fulltext (accessed 2.10.2023)</ref> <ref name=":4">World Health Organisation. [http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259615/9789241513487-eng.pdf?sequence=1 Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025]. 2017. Accessed 27 November 2018.</ref> Dementia is generally associated with age but early onset dementia also occurs. A study conducted by Alzheimer's society showed that 1 in 1400 individuals aged between 40-65 years, 1 in 100 individuals aged between 65-70 years, 1 in 25 individuals aged between 70-80 years and 1 in 6 individuals aged 80+ suffer from dementia. | ||

=== Etiology === | === Etiology === | ||

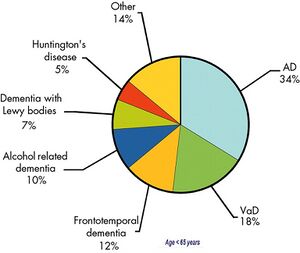

Damage to brain cells causes changes to cognitive, behavioural and emotional functions, causing dementia. | [[File:Epidemiology of young-onset dementia 2010 en.jpeg|thumb|Epidemiology, young-onset dementia]] | ||

Damage to [[Neurone|brain cells]] causes changes to cognitive, behavioural and emotional functions, causing dementia. Different types of dementia have different causes. Common types of dementia are: | |||

* [[Alzheimer's Disease]]: most common type. <ref name=":3">Robinson L, Tang E, Taylor J. [https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/350/bmj.h3029.full.pdf Clinical review. Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention]. BMJ. 2015;350:h3029. </ref><ref name=":4" /> It accounts for 60-70% of cases of dementia <ref name=":4" /> | |||

* Vascular Dementia: second most common type (following [[Stroke|cerebrovascular accident)]] <ref name=":3" /> | |||

* [[Lewy Body Disease|Lewy Body]] Dementia | |||

* [[Frontal Lobe|Fronto-Temporal]] Lobar Degeneration Dementia | |||

{{#ev:youtube|QuJFLr5Ib9k}}<ref>Alzheimer's SocietyWhat is frontotemporal dementia? - Alzheimer's Society (7)Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QuJFLr5Ib9k&feature=emb_logo</ref> | |||

* [[Huntington Disease|Huntington's Disease]] | |||

* [[Alcoholism|Alcohol]] related dementia (Korsakoff's syndrome) | |||

{{#ev:youtube|nv6iC7he4Nc}}<ref>Howcast.What Is Alcohol Dementia? | Alcoholism. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nv6iC7he4Nc&feature=emb_logo</ref> | |||

* [[Prion Diseases (or Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies)|Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease]] | |||

{{#ev:youtube|lS9jKVM7ZXo}}<ref>Mayo Clinic.CJD Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease - Mayo Clinic. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lS9jKVM7ZXo&feature=emb_logo</ref> | |||

== Risk Factors == | |||

Dementia risk factors can be categorised into modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. | |||

'''Modifiable risk factors include''':<ref>Kane RL, Butler M, Fink HA, Brasure M, Davila H, Desai P, Jutkowitz E, McCreedy E, Nelson VA, McCarten JR, Calvert C, Ratner E, Hemmy LS, Barclay T. Interventions to Prevent Age-Related Cognitive Decline, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Clinical Alzheimer’s-Type Dementia [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2017 Mar. Report No.: 17-EHC008-EF. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK442425/ {last access 10.08.2023]</ref><ref>Prince M, Albanese E, Guerchet M, Prina M. World Alzheimer Report 2014: Dementia and risk reduction: An analysis of protective and modifiable risk factors. Available from https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2014.pdf [last access 10.08.2023]</ref><ref>Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C. [https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)31363-6/fulltext?start=1047%3Fstart%3D1047%3Fstart%3D1047%3Fstart%3D1047?start=1047%3Fstart%3D1047%3Fstart%3D1047%3Fstart%3D1047 Dementia prevention, intervention, and care]. The Lancet. 2017 Dec 16;390(10113):2673-734.</ref> | |||

* [[ | * [[Physical Activity|Physical inactivity]]. | ||

* [[Smoking Cessation and Brief Intervention|Tobacco]] use. | |||

* Unhealthy diets. | |||

* Harmful use of [[Alcoholism|alcohol]]. | |||

* Social isolation. | |||

* Cognitive inactivity. | |||

'''Non-modifiable risk factors include''': | |||

* | * Age- is the primary risk factor for dementia<ref name=":4" /> | ||

* [[Genetic Conditions and Inheritance|Genetics]].<ref>Loy CT, Schofield PR, Turner AM, Kwok JB. [https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/11508/2/Loy13LancetFinalDraft.pdf Genetics of dementia]. Lancet. 2014. 383; 9919:828-40. | |||

</ref> | </ref> | ||

Certain medical conditions are associated with an increased risk of developing dementia, including [[hypertension]], [[diabetes]], hypercholesterolemia, [[obesity]] and [[depression]]. | |||

See [[Dementia: Risk Factors]] | |||

== Clinical Presentation == | == Clinical Presentation == | ||

Early signs of dementia are normally subtle, sometimes mimicking other patterns of ageing<ref name=":3" />. It can include<ref name=": | Early signs of dementia are normally subtle, sometimes mimicking other patterns of ageing<ref name=":3" />. | ||

'''It can include the following:<ref name=":0">Dementia Australia. What is dementia? https://www.dementia.org.au/about-dementia/what-is-dementia (accessed 26/09/2018).</ref><ref name=":1">Alzheimer's association. What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia (accessed 26/09/2018).</ref>''' | |||

* Progressive and frequent memory loss (mostly short-term) | * Progressive and frequent memory loss (mostly short-term) | ||

* Confusion | * Confusion | ||

* Personality changes | * Personality changes | ||

* Apathy and withdrawal | * Apathy and withdrawal | ||

* Loss of functional abilities to perform activities of daily living | * Loss of functional abilities to perform [[Activities of Daily Living|activities of daily living]] | ||

* Agitation, aggression, distress and psychosis | |||

Although some cases of dementia are reversible (e.g. hormonal or vitamin deficiencies), most are progressive, with a slow, gradual onset. Certain symptoms, mostly behavioural and psychological, can result from drug interactions, environmental factors, unreported pain and other illnesses<ref name=":0" />. | * [[Depression]] and Anxiety | ||

* Sleep problems | |||

* [[Parkinson's]] | |||

* [[Pain Behaviours|Pain]] | |||

* [[Falls]] | |||

* [[Diabetes]] | |||

* [[Urinary Incontinence]] | |||

* Sensory impairment<ref name=":5" /> | |||

* Paratonia<ref name=":7">Drenth H, Zuidema S, Bautmans I, Marinelli L, Kleiner G, Hobbelen H. Paratonia in Dementia: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;78(4):1615-1637. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200691. PMID: 33185600; PMCID: PMC7836054.</ref>,it is defined as motor abnormality induced by dementia. It has a devastating impact on the patient quality of life.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

Although some cases of dementia are reversible (e.g. [[Hormones|hormonal]] or vitamin deficiencies), most are progressive, with a slow, gradual onset. Certain symptoms, mostly behavioural and psychological, can result from drug interactions, environmental factors, unreported pain and other illnesses<ref name=":0" />. | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

General practitioners are usually the first port of call for diagnosis of dementia<ref name=":3" />. Making a diagnosis can be challenging. The [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/resources/dementia-assessment-management-and-support-for-people-living-with-dementia-and-their-carers-pdf-1837760199109 NICE | General practitioners are usually the first port of call for diagnosis of dementia<ref name=":3" />. Making a diagnosis can be challenging. The [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/resources/dementia-assessment-management-and-support-for-people-living-with-dementia-and-their-carers-pdf-1837760199109 NICE Guidelines for Dementia] recommend the following process for making a diagnosis. | ||

* | * Taking a history including cognitive, behavioural and psychological symptoms, and their impact on daily life. Ideally, a history should be taken from the individual with dementia symptoms | ||

* A physical examination with blood and urine tests to exclude reversible causes of cognitive decline | * A physical examination with blood and urine tests to exclude reversible causes of cognitive decline | ||

* Cognitive testing using a validated brief structured cognitive instrument such as | * Cognitive testing using a validated brief structured cognitive instrument such as the 10-point cognitive screener (10-CS) the 6-item cognitive impairment test (6CIT) the 6-item screener the Memory Impairment Screen (MIS) the [[Mini-Cog]] Test Your Memory (TYM). | ||

Diagnosis of the dementia subtype is critical for clinical management and anticipating the course of disease<ref name=":3" />. Certain types of dementia are diagnosed by medical history, physical examination, blood tests, and characteristic changes in thinking, behaviour and the effect on performance of activities of daily living. The diagnosis of dementia subtype can be difficult to diagnose as many of the symptoms and brain changes overlap. Secondary care services normally assist in the diagnosis of the specific subtypes of dementia with the use of imaging<ref name=":3" /> or examining cerebrospinal fluid<ref name=":5">National Institute for Clinical and Health Excellence. [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97 <nowiki>Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers: NICE guideline [NG97]</nowiki>]. 2018. Accessed 26 November 2018.</ref>. A pilot study developed a study protocol aimed at aiding the early detection of dementia disorders using the [[Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)|Timed Up-and-Go]] (TUG) test with the verbal task of naming different animals<ref>Cedervall Y, Stenberg AM, Åhman HB, Giedraitis V, Tinmark F, Berglund L, Halvorsen K, Ingelsson M, Rosendahl E, Åberg AC. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32150995/ Timed Up-and-Go Dual-Task Testing in the Assessment of Cognitive Function: A Mixed Methods Observational Study for Development of the UDDGait Protocol.] International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020 Jan;17(5):1715.</ref>. A research study suggests that poor visual acuity resulted in poorer executive function, which further caused more inadequate balance control, thus demonstrating the importance of assessing executive functions besides vision and balance in older individuals living with Alzheimer's dementia<ref>Hunter SW, Divine A, Madou E, Omana H, Hill KD, Johnson AM, Holmes JD, Wittich W. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32388070/ Executive function as a mediating factor between visual acuity and postural stability in cognitively healthy adults and adults with Alzheimer’s dementia.] Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2020 Apr 19:104078.</ref>. | Diagnosis of the dementia subtype is critical for clinical management and anticipating the course of disease<ref name=":3" />. Certain types of dementia are diagnosed by medical history, physical examination, blood tests, and characteristic changes in thinking, behaviour and the effect on performance of activities of daily living. The diagnosis of dementia subtype can be difficult to diagnose as many of the symptoms and brain changes overlap. Secondary care services normally assist in the diagnosis of the specific subtypes of dementia with the use of imaging<ref name=":3" /> or examining cerebrospinal fluid<ref name=":5">National Institute for Clinical and Health Excellence. [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97 <nowiki>Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers: NICE guideline [NG97]</nowiki>]. 2018. Accessed 26 November 2018.</ref>. A pilot study developed a study protocol aimed at aiding the early detection of dementia disorders using the [[Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)|Timed Up-and-Go]] (TUG) test with the verbal task of naming different animals<ref>Cedervall Y, Stenberg AM, Åhman HB, Giedraitis V, Tinmark F, Berglund L, Halvorsen K, Ingelsson M, Rosendahl E, Åberg AC. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32150995/ Timed Up-and-Go Dual-Task Testing in the Assessment of Cognitive Function: A Mixed Methods Observational Study for Development of the UDDGait Protocol.] International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020 Jan;17(5):1715.</ref>. A research study suggests that poor visual acuity resulted in poorer executive function, which further caused more inadequate balance control, thus demonstrating the importance of assessing executive functions besides vision and balance in older individuals living with Alzheimer's dementia<ref>Hunter SW, Divine A, Madou E, Omana H, Hill KD, Johnson AM, Holmes JD, Wittich W. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32388070/ Executive function as a mediating factor between visual acuity and postural stability in cognitively healthy adults and adults with Alzheimer’s dementia.] Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2020 Apr 19:104078.</ref>. | ||

== Differential Diagnosis == | == Differential Diagnosis == | ||

Dementia can have different causes, and the following conditions need to be treated and/or excluded first: | Dementia can have different causes, and the following conditions need to be treated and/or excluded first: | ||

* Vitamin B12 | * [[Vitamin B12 Deficiency|Vitamin B12 Deficienc]]<nowiki/>y<ref name=":3" /> | ||

* Hormone | * [[Hormones|Hormone]] Deficiencies (e.g. thyroid problems)<ref name=":3" /> | ||

* [[Depression]]<ref name=":3" /> | * [[Depression]]<ref name=":3" /> | ||

* Medication side-effects | * Medication side-effects | ||

* Alcohol | * Alcohol Abuse | ||

* Overmedication | * Overmedication | ||

* Infections | * Infections | ||

* | * [[Brain Tumors|Brain Tumours]] | ||

== Management == | == Management == | ||

Medical management should be sought as soon as symptoms start appearing, as some of the causes are treatable, and early diagnosis and management can minimise the disease process to allow most benefit from available treatments. A study suggests the need for optimal assessment, better communication among health care professionals for treating patients with dementia with multiple impairments<ref>Wolski L, Leroi I, Regan J, Dawes P, Charalambous AP, Thodi C, Prokopiou J, Villeneuve R, Helmer C, Yohannes AM, Himmelsbach I. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791251 The need for improved cognitive, hearing and vision assessments for older people with cognitive impairment: a qualitative study.] BMC geriatrics. 2019 Dec 1;19(1):328.</ref>. | Medical management should be sought as soon as symptoms start appearing, as some of the causes are treatable, and early diagnosis and management can minimise the disease process to allow the most benefit from available treatments. A study suggests the need for optimal assessment, better communication among health care professionals for treating patients with dementia with multiple impairments<ref>Wolski L, Leroi I, Regan J, Dawes P, Charalambous AP, Thodi C, Prokopiou J, Villeneuve R, Helmer C, Yohannes AM, Himmelsbach I. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791251 The need for improved cognitive, hearing and vision assessments for older people with cognitive impairment: a qualitative study.] BMC geriatrics. 2019 Dec 1;19(1):328.</ref>. | ||

FDA-approved medications to improve cognitive functions include cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine. Cholinesterase inhibitors prevent the breakdown of acetylcholine and can slow or delay the worsening of symptoms. Memantine is an NMDA agonist and decreases the activity of glutamine. Donepezil is approved for all stages of Alzheimer's disease, galantamine, and rivastigmine for mild to moderate stage and memantine for moderate to severe stage. | |||

Behavior symptoms include irritability, anxiety, and [[depression]]. Antidepressants like SSRI, antipsychotics, and anxiolytics can help with these symptoms. In addition, non-drug approaches like supportive care, memory training, physical exercise programs, mental and social stimulation must be employed in symptom control. | |||

[ | |||

Treatment of [[Sleep: Regulation and Assessment|sleep]] symptoms must be an important consideration in patients with dementia. Medication options include amitriptyline, lorazepam, zolpidem, temazepam, quetiapine, etc., Non-drug approaches include daily [[Therapeutic Exercise|exercise]], light therapy, sleep routine, avoiding [[Caffeine and Exercise|caffeine]] and alcohol, pain control, [[biofeedback]], and multicomponent [[Cognitive Behavioural Therapy|cognitive behavioural therapy]]. | |||

There are many other drugs that are still under investigation, such as anti-tau protein agents. So far, these have not shown promising results. | |||

Patients and their families should be counselled about the disease and its consequences. They should be provided with all the necessary information in regards to what to expect and how to react to it. Patients and their families should also be encouraged to seek social service consultations and to register with support groups and societies such as the Alzheimer's society. Driving restrictions may have to be imposed<ref name=":6" />. | |||

[https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/resources/dementia-assessment-management-and-support-for-people-living-with-dementia-and-their-carers-pdf-1837760199109 The NICE Guideline for Dementia] discusses pharmacological management of dementia according to subtype in depth. | |||

== | == Non-medical Management == | ||

Alongside drug interventions, non-pharmacological interventions are used to treat the symptoms of dementia. | |||

* | '''Non-pharmacological Management''' | ||

* Cognitive stimulation therapy<ref name=":5" /><ref>Km K, Han JW, So Y, Seo J, Kim YJ, Park JH, Lee SB, Lee JJ, Jeong H, Lim TH, Kim KW. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5639131/ Cognitive Stimulation as a Therapeutic Modality for Dementia: A Meta-Analysis]. Psychiatry Investig. 2017. 14; 5: 626–639. Accessed 26 November 2018.</ref> for mild-to-moderate dementia has been shown to be clinically effective and cost-effective as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. <ref>Knapp M, Iemmi V, Romeo R. [http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/45540/1/Knapp_Dementia_care_costs.pdf Dementia care costs and outcomes: a systematic review]. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;28:551-61. Accessed 26 Novmeber 2018.</ref> Cognitive stimulation therapy can be administrated by anyone working with dementia patients; carers, nurses or occupational therapists. <ref>Streater A, Aguirre E, Spector A, Orrell M. Cognitive stimulation therapy for people with dementia in practice: A service evaluation. Br Jour Occup Ther. 2016. 79; 9: 574–580. Accessed 27 November 2018. </ref> | |||

* | * Reminiscence therapy for mild to moderate dementia. <ref name=":5" /><ref>Woods B, O'Philbin L, Farrell EM, Spector AE, Orrell M. [https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001120.pub3/full Reminiscence therapy for dementia]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; 3: CD001120. Accessed 27 November 2018. </ref> | ||

* | * Cognitive rehabilitation or occupational therapy (working on functional goals of the individual and/or their carers). <ref name=":5" /> | ||

'''Lifestyle Modifications''' | |||

* | * Regular exercise and an active lifestyle. <ref name=":0" />Very effective in the management of the depression component of dementia. | ||

* | * Stimulating, personalised daily activities. <ref name=":5" /> | ||

== | == Physiotherapy Management == | ||

Physiotherapy is not a modality used to treat the underlying cause of dementia, but exercise can be used in the prevention of dementia and minimising the effects of dementia e.g. reduced mobility and pain. In addition, well-rounded knowledge of dementia is important in the management of patients with dementia presenting to physiotherapy for other conditions. A study<ref>Sondell A, Littbrand H, Holmberg H, Lindelöf N, Rosendahl E. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31781732 Is the Effect of a High-Intensity Functional Exercise Program on Functional Balance Influenced by Applicability and Motivation among Older People with Dementia in Nursing Homes?]. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2019 Dec 1;23(10):1011-20.</ref> suggests that a high-intensity functional exercise program has positive outcomes on [[balance]] in these patients. | |||

Physiotherapists can play a role in customising exercise programmes. Research has shown positive effects that exercise can prevent or delay the onset of dementia, by slowing down the cognitive decline. <ref>Ko MH. [https://synapse.koreamed.org/search.php?where=aview&id=10.12786/bn.2015.8.1.24&code=0176BN&vmode=FULL Exercise for Dementia.] Brain & Neurorehabilitation 2015. 8; 1: 24-8. Accessed 27 November 2018.</ref><ref name=":2">Rolland Y. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781119952930.ch77 Exercise and Dementia]. In: Sinclair AJ, Morley JE, Vellas B editors. Pathy's Principles and Practice of Geriatric Medicine. 2012;1:911-21. Accessed 27 November 2018.</ref> This can lead to improved quality of life and slowing down of functional decline expected with the disease process. <ref name=":2" /> There is also some evidence that exercise therapy can improve the ability of people with dementia in performing activities of daily living. <ref>Forbes D, Forbes SC, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Forbes S. [https://www.cochrane.org/CD006489/DEMENTIA_exercise-programs-for-people-with-dementia Exercise programs for people with dementia]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; 4: CD006489. Accessed 26 November 2018.</ref> The cross-sectional study published in Feb 2020 suggests a positive association between global cognitive function and self-paced gait speed in very old people. <ref>Öhlin J, Ahlgren A, Folkesson R, Gustafson Y, Littbrand H, Olofsson B, Toots A. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32005103/ The association between cognition and gait in a representative sample of very old people–the influence of dementia and walking aid use.] BMC geriatrics. 2020 Dec 1;20(1):34.</ref> A randomized controlled trial<ref>Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Makino K, Nakakubo S, Liu-Ambrose T, Shimada H. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31906021-exercise-and-horticultural-programs-for-older-adults-with-depressive-symptoms-and-memory-problems-a-randomized-controlled-trial/ Exercise and Horticultural Programs for Older Adults with Depressive Symptoms and Memory Problems: A Randomized Controlled Trial.] Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020 Jan;9(1):99.</ref> suggests favorable outcomes with exercise and horticultural intervention programs for older adults with depression and memory problems. Another randomised controlled study suggests that action observation (motor-related information available through the visual function) with gait training provides more significant benefits for gait and cognitive performances in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment.<ref>Rojasavastera R, Bovonsunthonchai S, Hiengkaew V, Senanarong V. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7304276/ Action observation combined with gait training to improve gait and cognition in elderly with mild cognitive impairment A randomized controlled trial.] Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 2020 Jun;14(2):118-27.</ref> | |||

== | == Occupational Therapy == | ||

[https://www.aota.org/about/what-is-ot Occupational therapy] can be a valuable source of assistance for patients with dementia and their family. An occupational therapist (OT) works with clients to increase their level of independence in their daily tasks.<ref>Dementia and Alzheimer’s [Internet]. Theotpractice.co.uk. [cited 2023 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.theotpractice.co.uk/how-we-help/conditions/dementia-and-altzheimers</ref> | |||

Occupational therapy interventions may include:<ref>Piersol CV, Jensen L, Lieberman D, Arbesman M. [https://research.aota.org/ajot/article/72/1/7201390010p1/6404/Occupational-Therapy-Interventions-for-People-With Occupational Therapy Interventions for People With Alzheimer's Disease.] Am J Occup Ther. 2018 Jan/Feb;72(1):7201390010p1-7201390010p6.</ref> | |||

* ADL training or activity modification to improve or maintain ADL performance. | |||

* | * Errorless learning and prompting strategies to improve ADL performance. | ||

* | * Ambient music and multisensory interventions to improve short-term behavior. | ||

* | * Exercise-based interventions to improve or maintain ADL performance, including functional mobility and sleep.Monitoring devices to prevent falls in the home. | ||

** | * Communication skills training to promote caregiver quality of life and well-being. | ||

* Multicomponent psychoeducational interventions (education, skill training, and coping strategies) to improve caregiver well-being and moderate evidence to delay nursing home placement. | |||

== | == Deterrence and Patient Education == | ||

The diagnosis of dementia can be stressful and overwhelming for the patients and their families. Patient education must be an important part of the clinical management of patients with dementia. Counselling must be given about regular clinic visits, medication compliance, a healthy diet, exercise, and sleep hygiene. Support groups can help with the reduction of issues like anxiety, frustration, anger, loneliness, and depression. The patient should be counselled about the diagnosis and the prognosis. Creating an individualized care plan can empower the patient. | |||

See the Physiopedia guides for carers [[Promoting Independence for Persons With Dementia|here]] and [[Carers guide to dementia|here]] for further information on supporting carers of people with dementia. | |||

== | == Prognosis == | ||

The prognosis with dementia is poor. Dementia is often a progressive condition with no cure or treatment. 1-year mortality rate was 30-40% while the 5-year mortality rate was 60-65%. Men had a higher risk than women. Mortality rates among admitted patients with dementia was higher than those with [[Cardiovascular Disease|cardiovascular diseases.]] <ref name=":6" /> | |||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

The following list is from a [http://www.neurodegenerationresearch.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/JPND-Report-Fountain.pdf review] of useful outcome measures for dementia. | |||

'''Mood''' | |||

*[http://www.primaris.org/sites/default/files/resources/Depression/depression_cornell%20scale%20for%20depression%20final.pdf Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia] | |||

</ | *[[Geriatric Depression Scale]] | ||

<br>'''Quality of Life''' | |||

* Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease | |||

* The Dementia Quality of Life Instrument | |||

*[https://www.bsms.ac.uk/_pdf/cds/demqol-questionnaire.pdf DEMQoL] | |||

*[https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2009/ha/bgrd/backgroundfile-24240.pdf QUALID] | |||

<br>'''Health-related Quality of Life''' | |||

*[[EQ-5D]] | |||

<br>'''Activities of Daily Living''' | |||

*[https://consultgeri.org/try-this/general-assessment/issue-23.pdf Lawton – PSMS & IADL] | |||

*[http://www.medafile.com/cln/ADCSADLm.htm Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study – Activities of Daily Living Inventory] | |||

*[http://www.wellnessofmind.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Bristol-Activities-of-Daily-Living-Scale.pdf Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale] | |||

*[https://www.inesss.qc.ca/fileadmin/doc/INESSS/Rapports/Geriatrie/MA_TNC_DAD_scale.pdf The disability assessment for dementia] | |||

<br>'''Pain''' | |||

*[https://apsoc.org.au/PDF/Publications/Abbey_Pain_Scale.pdf Abbey Pain Scale] | |||

*[[Visual Analogue Scale|VAS]] | |||

<br>'''Behaviour''' | |||

*[https://www.alz.org/national/documents/C_ASSESS-RevisedMemoryandBehCheck.pdf Revised Memory and behaviour problems checklist] | |||

*[https://download.lww.com/wolterskluwer_vitalstream_com/PermaLink/CONT/A/CONT_21_3_2015_02_26_KAUFER_2015-10_SDC2.pdf Neuropsychiatric Inventory] | |||

*[http://www.dementiamanagementstrategy.com/file.axd?id=c9f7405f-3596-4f5f-9f8d-f322e5188678 Neuropsychiatric Inventory (Nursing Home)] | |||

* CAMI | |||

<br>'''Reaction to Behaviour''' | |||

*[https://www.alz.org/national/documents/C_ASSESS-RevisedMemoryandBehCheck.pdf Revised Memory and behaviour problems checklist] | |||

*[https://download.lww.com/wolterskluwer_vitalstream_com/PermaLink/CONT/A/CONT_21_3_2015_02_26_KAUFER_2015-10_SDC2.pdf Neuropsychiatric Inventory with Caregiver Distress Scale] | |||

*[http://www.dementiamanagementstrategy.com/file.axd?id=c9f7405f-3596-4f5f-9f8d-f322e5188678 Neuropsychiatric Inventory in Nursing Homes] | |||

<br>'''Carer Mood''' | |||

*[http://www.assessmentpsychology.com/HAM-D.pdf Hamilton Depression Rating Scale] | |||

* General Health Questionnaire | |||

*[http://www.chcr.brown.edu/pcoc/cesdscale.pdf Centre for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale] | |||

<br>'''Carer Burden''' | |||

*[http://dementiapathways.ie/_filecache/edd/c3c/89-zarit_burden_interview.pdf Zarit Burden Interview] | |||

* Sense of competence scale | |||

* Relative Stress Scale | |||

<br>'''Carer Health-related Quality of Life''' | |||

*[[36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36)|SF-36]] | |||

*[http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/en/english_whoqol.pdf WHOQoL-Bref] | |||

*[[EQ-5D]]. A cross-sectional study suggests that the EQ-5D-3L could be a useful tool for quality of life assessment in nursing home residents with cognitive impairment. <ref>Pérez-Ros P, Martínez-Arnau FM. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7400476/ EQ-5D-3L for Assessing Quality of Life in Older Nursing Home Residents with Cognitive Impairment.] Life. 2020 Jul;10(7):100.</ref> | |||

<br>'''Resource Utilisation''' | |||

*[https://www.pssru.ac.uk/csri/files/2017/10/TYOCPA-CSRI-v2.pdf Client Service Receipt Inventory] | |||

*[https://rudinstrument.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/rud-3-2-sample.pdf The Resource Utilization in Dementia (RUD) Instrument] | |||

<br>'''Staff Carer Morale''' | |||

* Maslach Burnout Inventory | |||

== Resources == | == Resources == | ||

| Line 298: | Line 203: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Dementia]] | [[Category:Dementia]] | ||

[[Category:Conditions]] | [[Category:Conditions]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:18, 20 November 2023

Original Editors - Leana Louw

Top Contributors - Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Leana Louw, Lauren Lopez, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Aminat Abolade, Tony Lowe, Shaimaa Eldib, Naomi O'Reilly, Kalyani Yajnanarayan, Safiya Naz, Ewa Jaraczewska, Carina Therese Magtibay and Aya Alhindi

Definition[edit | edit source]

Dementia describes an overall decline in memory and other thinking skills severe enough to reduce a person's ability to perform everyday activities. It is characterized by the progressive and persistent deterioration of cognitive function. Patients with dementia have problems with cognition, behaviour, and functional activities of everyday life. In addition, affected patients have memory loss and lack of insight into their problems.[1]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The pathophysiology of dementia is not understood completely. Most types of dementia, except vascular dementia, are caused by the accumulation of native proteins in the brain.

- Alzheimer Disease (AD) is characterized by widespread atrophy of the cortex and deposition of amyloid plaques and tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein in the neurons which contribute to their degeneration. A genetic basis has been established for both early and late-onset AD. Certain factors like depression, traumatic head injury, cardiovascular disease, family history of dementia, smoking, and the presence of APOE e4 allele have been shown to increase the risk of development of AD.

- Lewy Body Dementia is characterized by the intracellular accumulation of Lewy bodies (which are insoluble aggregates of alpha-synuclein) in the neurons, mainly in the cortex.

- Frontotemporal Dementia is characterized by the deposition of ubiquitinated TDP-43 and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins in the frontal and temporal lobes leading to dementia, early personality, and behavioral changes, and aphasia.

- Vascular dementia is caused by ischemic injury to the brain (e.g., stroke), leading to permanent neuronal death.[1]

The hippocampus though is often involved and contributes to the well-known symptoms of memory loss. Cells in this region are normally first to be damaged in Alzheimer's Disease[3], resulting in the common symptom of memory loss. Changes in hippocampal volume (a reduction) are seen with common patterns of aging but are exacerbated in Alzheimer's. [4]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Dementia affects approximately 47 million people worldwide and is projected to increase to 75 million in 2030 and 152·8 (130·8–175·9) million by 2050.[5] [6] Dementia is generally associated with age but early onset dementia also occurs. A study conducted by Alzheimer's society showed that 1 in 1400 individuals aged between 40-65 years, 1 in 100 individuals aged between 65-70 years, 1 in 25 individuals aged between 70-80 years and 1 in 6 individuals aged 80+ suffer from dementia.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Damage to brain cells causes changes to cognitive, behavioural and emotional functions, causing dementia. Different types of dementia have different causes. Common types of dementia are:

- Alzheimer's Disease: most common type. [7][6] It accounts for 60-70% of cases of dementia [6]

- Vascular Dementia: second most common type (following cerebrovascular accident) [7]

- Lewy Body Dementia

- Fronto-Temporal Lobar Degeneration Dementia

- Huntington's Disease

- Alcohol related dementia (Korsakoff's syndrome)

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Dementia risk factors can be categorised into modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors.

Modifiable risk factors include:[11][12][13]

- Physical inactivity.

- Tobacco use.

- Unhealthy diets.

- Harmful use of alcohol.

- Social isolation.

- Cognitive inactivity.

Non-modifiable risk factors include:

Certain medical conditions are associated with an increased risk of developing dementia, including hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, obesity and depression.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Early signs of dementia are normally subtle, sometimes mimicking other patterns of ageing[7].

It can include the following:[15][16]

- Progressive and frequent memory loss (mostly short-term)

- Confusion

- Personality changes

- Apathy and withdrawal

- Loss of functional abilities to perform activities of daily living

- Agitation, aggression, distress and psychosis

- Depression and Anxiety

- Sleep problems

- Parkinson's

- Pain

- Falls

- Diabetes

- Urinary Incontinence

- Sensory impairment[17]

- Paratonia[18],it is defined as motor abnormality induced by dementia. It has a devastating impact on the patient quality of life.[18]

Although some cases of dementia are reversible (e.g. hormonal or vitamin deficiencies), most are progressive, with a slow, gradual onset. Certain symptoms, mostly behavioural and psychological, can result from drug interactions, environmental factors, unreported pain and other illnesses[15].

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

General practitioners are usually the first port of call for diagnosis of dementia[7]. Making a diagnosis can be challenging. The NICE Guidelines for Dementia recommend the following process for making a diagnosis.

- Taking a history including cognitive, behavioural and psychological symptoms, and their impact on daily life. Ideally, a history should be taken from the individual with dementia symptoms

- A physical examination with blood and urine tests to exclude reversible causes of cognitive decline

- Cognitive testing using a validated brief structured cognitive instrument such as the 10-point cognitive screener (10-CS) the 6-item cognitive impairment test (6CIT) the 6-item screener the Memory Impairment Screen (MIS) the Mini-Cog Test Your Memory (TYM).

Diagnosis of the dementia subtype is critical for clinical management and anticipating the course of disease[7]. Certain types of dementia are diagnosed by medical history, physical examination, blood tests, and characteristic changes in thinking, behaviour and the effect on performance of activities of daily living. The diagnosis of dementia subtype can be difficult to diagnose as many of the symptoms and brain changes overlap. Secondary care services normally assist in the diagnosis of the specific subtypes of dementia with the use of imaging[7] or examining cerebrospinal fluid[17]. A pilot study developed a study protocol aimed at aiding the early detection of dementia disorders using the Timed Up-and-Go (TUG) test with the verbal task of naming different animals[19]. A research study suggests that poor visual acuity resulted in poorer executive function, which further caused more inadequate balance control, thus demonstrating the importance of assessing executive functions besides vision and balance in older individuals living with Alzheimer's dementia[20].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Dementia can have different causes, and the following conditions need to be treated and/or excluded first:

- Vitamin B12 Deficiency[7]

- Hormone Deficiencies (e.g. thyroid problems)[7]

- Depression[7]

- Medication side-effects

- Alcohol Abuse

- Overmedication

- Infections

- Brain Tumours

Management[edit | edit source]

Medical management should be sought as soon as symptoms start appearing, as some of the causes are treatable, and early diagnosis and management can minimise the disease process to allow the most benefit from available treatments. A study suggests the need for optimal assessment, better communication among health care professionals for treating patients with dementia with multiple impairments[21].

FDA-approved medications to improve cognitive functions include cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine. Cholinesterase inhibitors prevent the breakdown of acetylcholine and can slow or delay the worsening of symptoms. Memantine is an NMDA agonist and decreases the activity of glutamine. Donepezil is approved for all stages of Alzheimer's disease, galantamine, and rivastigmine for mild to moderate stage and memantine for moderate to severe stage.

Behavior symptoms include irritability, anxiety, and depression. Antidepressants like SSRI, antipsychotics, and anxiolytics can help with these symptoms. In addition, non-drug approaches like supportive care, memory training, physical exercise programs, mental and social stimulation must be employed in symptom control.

Treatment of sleep symptoms must be an important consideration in patients with dementia. Medication options include amitriptyline, lorazepam, zolpidem, temazepam, quetiapine, etc., Non-drug approaches include daily exercise, light therapy, sleep routine, avoiding caffeine and alcohol, pain control, biofeedback, and multicomponent cognitive behavioural therapy.

There are many other drugs that are still under investigation, such as anti-tau protein agents. So far, these have not shown promising results.

Patients and their families should be counselled about the disease and its consequences. They should be provided with all the necessary information in regards to what to expect and how to react to it. Patients and their families should also be encouraged to seek social service consultations and to register with support groups and societies such as the Alzheimer's society. Driving restrictions may have to be imposed[1].

The NICE Guideline for Dementia discusses pharmacological management of dementia according to subtype in depth.

Non-medical Management[edit | edit source]

Alongside drug interventions, non-pharmacological interventions are used to treat the symptoms of dementia.

Non-pharmacological Management

- Cognitive stimulation therapy[17][22] for mild-to-moderate dementia has been shown to be clinically effective and cost-effective as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. [23] Cognitive stimulation therapy can be administrated by anyone working with dementia patients; carers, nurses or occupational therapists. [24]

- Reminiscence therapy for mild to moderate dementia. [17][25]

- Cognitive rehabilitation or occupational therapy (working on functional goals of the individual and/or their carers). [17]

Lifestyle Modifications

- Regular exercise and an active lifestyle. [15]Very effective in the management of the depression component of dementia.

- Stimulating, personalised daily activities. [17]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy is not a modality used to treat the underlying cause of dementia, but exercise can be used in the prevention of dementia and minimising the effects of dementia e.g. reduced mobility and pain. In addition, well-rounded knowledge of dementia is important in the management of patients with dementia presenting to physiotherapy for other conditions. A study[26] suggests that a high-intensity functional exercise program has positive outcomes on balance in these patients.

Physiotherapists can play a role in customising exercise programmes. Research has shown positive effects that exercise can prevent or delay the onset of dementia, by slowing down the cognitive decline. [27][28] This can lead to improved quality of life and slowing down of functional decline expected with the disease process. [28] There is also some evidence that exercise therapy can improve the ability of people with dementia in performing activities of daily living. [29] The cross-sectional study published in Feb 2020 suggests a positive association between global cognitive function and self-paced gait speed in very old people. [30] A randomized controlled trial[31] suggests favorable outcomes with exercise and horticultural intervention programs for older adults with depression and memory problems. Another randomised controlled study suggests that action observation (motor-related information available through the visual function) with gait training provides more significant benefits for gait and cognitive performances in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment.[32]

Occupational Therapy[edit | edit source]

Occupational therapy can be a valuable source of assistance for patients with dementia and their family. An occupational therapist (OT) works with clients to increase their level of independence in their daily tasks.[33]

Occupational therapy interventions may include:[34]

- ADL training or activity modification to improve or maintain ADL performance.

- Errorless learning and prompting strategies to improve ADL performance.

- Ambient music and multisensory interventions to improve short-term behavior.

- Exercise-based interventions to improve or maintain ADL performance, including functional mobility and sleep.Monitoring devices to prevent falls in the home.

- Communication skills training to promote caregiver quality of life and well-being.

- Multicomponent psychoeducational interventions (education, skill training, and coping strategies) to improve caregiver well-being and moderate evidence to delay nursing home placement.

Deterrence and Patient Education[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of dementia can be stressful and overwhelming for the patients and their families. Patient education must be an important part of the clinical management of patients with dementia. Counselling must be given about regular clinic visits, medication compliance, a healthy diet, exercise, and sleep hygiene. Support groups can help with the reduction of issues like anxiety, frustration, anger, loneliness, and depression. The patient should be counselled about the diagnosis and the prognosis. Creating an individualized care plan can empower the patient.

See the Physiopedia guides for carers here and here for further information on supporting carers of people with dementia.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The prognosis with dementia is poor. Dementia is often a progressive condition with no cure or treatment. 1-year mortality rate was 30-40% while the 5-year mortality rate was 60-65%. Men had a higher risk than women. Mortality rates among admitted patients with dementia was higher than those with cardiovascular diseases. [1]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The following list is from a review of useful outcome measures for dementia.

Mood

Quality of Life

Health-related Quality of Life

Activities of Daily Living

- Lawton – PSMS & IADL

- Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study – Activities of Daily Living Inventory

- Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale

- The disability assessment for dementia

Pain

Behaviour

- Revised Memory and behaviour problems checklist

- Neuropsychiatric Inventory

- Neuropsychiatric Inventory (Nursing Home)

- CAMI

Reaction to Behaviour

- Revised Memory and behaviour problems checklist

- Neuropsychiatric Inventory with Caregiver Distress Scale

- Neuropsychiatric Inventory in Nursing Homes

Carer Mood

- Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- General Health Questionnaire

- Centre for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale

Carer Burden

- Zarit Burden Interview

- Sense of competence scale

- Relative Stress Scale

Carer Health-related Quality of Life

- SF-36

- WHOQoL-Bref

- EQ-5D. A cross-sectional study suggests that the EQ-5D-3L could be a useful tool for quality of life assessment in nursing home residents with cognitive impairment. [35]

Resource Utilisation

Staff Carer Morale

- Maslach Burnout Inventory

Resources [edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Emmady PD, Tadi P, Del Pozo E. Dementia (Nursing). Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557444/ (accessed 20.9.2021)

- ↑ AlzheimersResearch UK What is dementia? Alzheimer's Research UK Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HobxLbPhrMc&feature=emb_logo

- ↑ Maruszak A, Thuret S. Why looking at the whole hippocampus is not enough—a critical role for anteroposterior axis, subfield and activation analyses to enhance predictive value of hippocampal changes for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014; 8: 95.

- ↑ den Heijer T, van der Lign F, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, van der Lugt A, Krestin GP, Niessen WJ, Breteler MMB. A 10-year follow-up of hippocampal volume on magnetic resonance imaging in early dementia and cognitive decline. Brain. 2010. 133; 4: 1163–1172.

- ↑ Nichols E, Steinmetz JD, Vollset SE, Fukutaki K, Chalek J, Abd-Allah F, Abdoli A, Abualhasan A, Abu-Gharbieh E, Akram TT, Al Hamad H. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Public Health. 2022 Feb 1;7(2):e105-25.Available:https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(21)00249-8/fulltext (accessed 2.10.2023)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 World Health Organisation. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. 2017. Accessed 27 November 2018.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Robinson L, Tang E, Taylor J. Clinical review. Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ. 2015;350:h3029.

- ↑ Alzheimer's SocietyWhat is frontotemporal dementia? - Alzheimer's Society (7)Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QuJFLr5Ib9k&feature=emb_logo

- ↑ Howcast.What Is Alcohol Dementia? | Alcoholism. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nv6iC7he4Nc&feature=emb_logo

- ↑ Mayo Clinic.CJD Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease - Mayo Clinic. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lS9jKVM7ZXo&feature=emb_logo

- ↑ Kane RL, Butler M, Fink HA, Brasure M, Davila H, Desai P, Jutkowitz E, McCreedy E, Nelson VA, McCarten JR, Calvert C, Ratner E, Hemmy LS, Barclay T. Interventions to Prevent Age-Related Cognitive Decline, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Clinical Alzheimer’s-Type Dementia [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2017 Mar. Report No.: 17-EHC008-EF. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK442425/ {last access 10.08.2023]

- ↑ Prince M, Albanese E, Guerchet M, Prina M. World Alzheimer Report 2014: Dementia and risk reduction: An analysis of protective and modifiable risk factors. Available from https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2014.pdf [last access 10.08.2023]

- ↑ Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet. 2017 Dec 16;390(10113):2673-734.

- ↑ Loy CT, Schofield PR, Turner AM, Kwok JB. Genetics of dementia. Lancet. 2014. 383; 9919:828-40.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Dementia Australia. What is dementia? https://www.dementia.org.au/about-dementia/what-is-dementia (accessed 26/09/2018).

- ↑ Alzheimer's association. What is dementia? https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia (accessed 26/09/2018).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 National Institute for Clinical and Health Excellence. Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers: NICE guideline [NG97]. 2018. Accessed 26 November 2018.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Drenth H, Zuidema S, Bautmans I, Marinelli L, Kleiner G, Hobbelen H. Paratonia in Dementia: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;78(4):1615-1637. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200691. PMID: 33185600; PMCID: PMC7836054.

- ↑ Cedervall Y, Stenberg AM, Åhman HB, Giedraitis V, Tinmark F, Berglund L, Halvorsen K, Ingelsson M, Rosendahl E, Åberg AC. Timed Up-and-Go Dual-Task Testing in the Assessment of Cognitive Function: A Mixed Methods Observational Study for Development of the UDDGait Protocol. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020 Jan;17(5):1715.

- ↑ Hunter SW, Divine A, Madou E, Omana H, Hill KD, Johnson AM, Holmes JD, Wittich W. Executive function as a mediating factor between visual acuity and postural stability in cognitively healthy adults and adults with Alzheimer’s dementia. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2020 Apr 19:104078.

- ↑ Wolski L, Leroi I, Regan J, Dawes P, Charalambous AP, Thodi C, Prokopiou J, Villeneuve R, Helmer C, Yohannes AM, Himmelsbach I. The need for improved cognitive, hearing and vision assessments for older people with cognitive impairment: a qualitative study. BMC geriatrics. 2019 Dec 1;19(1):328.

- ↑ Km K, Han JW, So Y, Seo J, Kim YJ, Park JH, Lee SB, Lee JJ, Jeong H, Lim TH, Kim KW. Cognitive Stimulation as a Therapeutic Modality for Dementia: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Investig. 2017. 14; 5: 626–639. Accessed 26 November 2018.

- ↑ Knapp M, Iemmi V, Romeo R. Dementia care costs and outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;28:551-61. Accessed 26 Novmeber 2018.

- ↑ Streater A, Aguirre E, Spector A, Orrell M. Cognitive stimulation therapy for people with dementia in practice: A service evaluation. Br Jour Occup Ther. 2016. 79; 9: 574–580. Accessed 27 November 2018.

- ↑ Woods B, O'Philbin L, Farrell EM, Spector AE, Orrell M. Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; 3: CD001120. Accessed 27 November 2018.

- ↑ Sondell A, Littbrand H, Holmberg H, Lindelöf N, Rosendahl E. Is the Effect of a High-Intensity Functional Exercise Program on Functional Balance Influenced by Applicability and Motivation among Older People with Dementia in Nursing Homes?. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2019 Dec 1;23(10):1011-20.

- ↑ Ko MH. Exercise for Dementia. Brain & Neurorehabilitation 2015. 8; 1: 24-8. Accessed 27 November 2018.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Rolland Y. Exercise and Dementia. In: Sinclair AJ, Morley JE, Vellas B editors. Pathy's Principles and Practice of Geriatric Medicine. 2012;1:911-21. Accessed 27 November 2018.

- ↑ Forbes D, Forbes SC, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Forbes S. Exercise programs for people with dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; 4: CD006489. Accessed 26 November 2018.

- ↑ Öhlin J, Ahlgren A, Folkesson R, Gustafson Y, Littbrand H, Olofsson B, Toots A. The association between cognition and gait in a representative sample of very old people–the influence of dementia and walking aid use. BMC geriatrics. 2020 Dec 1;20(1):34.

- ↑ Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Makino K, Nakakubo S, Liu-Ambrose T, Shimada H. Exercise and Horticultural Programs for Older Adults with Depressive Symptoms and Memory Problems: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020 Jan;9(1):99.

- ↑ Rojasavastera R, Bovonsunthonchai S, Hiengkaew V, Senanarong V. Action observation combined with gait training to improve gait and cognition in elderly with mild cognitive impairment A randomized controlled trial. Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 2020 Jun;14(2):118-27.

- ↑ Dementia and Alzheimer’s [Internet]. Theotpractice.co.uk. [cited 2023 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.theotpractice.co.uk/how-we-help/conditions/dementia-and-altzheimers

- ↑ Piersol CV, Jensen L, Lieberman D, Arbesman M. Occupational Therapy Interventions for People With Alzheimer's Disease. Am J Occup Ther. 2018 Jan/Feb;72(1):7201390010p1-7201390010p6.

- ↑ Pérez-Ros P, Martínez-Arnau FM. EQ-5D-3L for Assessing Quality of Life in Older Nursing Home Residents with Cognitive Impairment. Life. 2020 Jul;10(7):100.