Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: Difference between revisions

Leana Louw (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (34 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Sigrid Bortels|Sigrid Bortels]] | '''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Sigrid Bortels|Sigrid Bortels]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | |||

== | The most powerful ligament in the knee joint is the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).<ref>Rhatomy S, Utomo DN, Suroto H, Mahyudin F. [https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S2049080120303101?token=67AF79F691B8B41147CB1C66B93D4FE1C819220DC17449775E534E2C138D2C36C95ED55CC23CC3C3C8038617079DF856&originRegion=us-east-1&originCreation=20221101165705 Posterior cruciate ligament research output in asian countries from 2009-2019: A systematic review]. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2020 Nov 1;59:76-80.</ref> The role of the PCL is to prevent the tibia from moving backwards relative to the femur.<ref>Xie, W.Q., He, M., He, Y.Q., Yu, D.J., Jin, H.F., Yu, F. and Li, Y.S., 2021. [https://josr-online.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13018-021-02443-0 The effects of posterior cruciate ligament rupture on the biomechanical and histological characteristics of the medial collateral ligament: an animal study.] ''Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research'', ''16''(1), pp.1-9.</ref>Injuries to the PCL often occur with other knee structures (ligaments, meniscus) while infrequently occurring in isolation. <ref>Longo UG, Viganò M, Candela V, De Girolamo L, Cella E, Thiebat G, Salvatore G, Ciccozzi M, Denaro V. [https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/10/3/499/htm Epidemiology of posterior cruciate ligament reconstructions in Italy: a 15-year study. Journal of clinical medicine.] 2021 Feb 1;10(3):499.</ref>PCL injury alone accounts for approximately 2 per 100,000 people annually. <ref>Knapik DM, Gopinatth V, Jackson GR, Chahla J, Smith MV, Matava MJ, Brophy RH. [https://jeo-esska.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40634-022-00541-4 Global variation in isolated posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction]. Journal of experimental orthopaedics. 2022 Dec;9(1):1-2.</ref> | ||

Injury to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) can range from a stretch to a total tear or rupture of the ligament. These injuries are less | Injury to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) can range from a stretch to a total tear or rupture of the ligament. These injuries are relatively uncommon.<ref>Shin J, Maak TG. Arthroscopic Transtibial PCL Reconstruction: Surgical Technique and Clinical Outcomes. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018;11(2):307-15.</ref> They occur less frequently than [[Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injury|anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries]] as the PCL is broader and stronger.<ref name="p1">Medscape. Drugs & Diseases, Sport Medicine. Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/90514-overview (accessed 20/08/2018).</ref> | ||

== Clinically | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

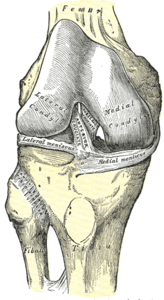

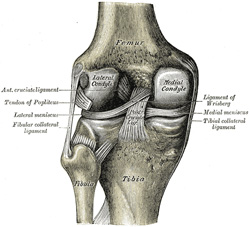

The PCL is one of the two cruciate ligaments of the [[knee]]. It acts as the major | The PCL is one of the two cruciate ligaments of the [[knee]]. It acts as the major stabilising ligament of the knee. and prevents the tibia from excessive posterior displacement in relation to the femur. It also functions to prevent hyper-extension and limits internal rotation, adduction and abduction at the knee joint.<ref name="p1" /> The PCL is twice as thick as the [[Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Reconstruction|ACL]] which results in less injuries than the ACL due to the stronger nature. As a result, PCL injuries are less common than [[Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Reconstruction|ACL]] injuries. | ||

It originates at the internal surface of the medial femoral condyle and inserts on the | It originates at the internal surface of the medial femoral condyle and inserts on the centre of the posterior aspect of the tibial plateau, 1 cm below the articular surface of the tibia<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p2">Paulsen F, Waschke J, Sobotta. Lower extremities, Knee Joint. Elsevier, 2010. p 272-276.</ref>. It crosses the [[Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Reconstruction|ACL]] to form an 'X'. The PCL consists of two inseparable bundles: the wide anterolateral (AL) bundle and the smaller posteromedial (PM) bundle.<ref name="p1" /> The AL bundle is most tight in mid-flexion and internal rotation of the knee, while the PM bundle is most tight in extension and deep flexion of the knee. The orientation of the fibres varies between bundles. The AL bundle is more horizontally orientated in extension and becomes more vertical as the knee is flexed beyond 30°. The PM bundle is vertically orientated in knee extension and becomes more horizontal through a similar range of motion.<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p2" /><br> | ||

{| | {| cellpadding="1" cellspacing="1" border="0" | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[File:ACL diagram from anterior.png|center|thumb|300x300px|Anterior view knee]] | |[[File:ACL diagram from anterior.png|center|thumb|300x300px|Anterior view knee]] | ||

| Line 22: | Line 21: | ||

|} | |} | ||

== Epidemiology/ | == Epidemiology/Aetiology == | ||

=== Epidemiology === | === Epidemiology === | ||

The mean age of people with acute PCL injuries range between 20-30's. | The mean age of people with acute PCL injuries range between 20-30's. While injuries to the PCL can occur in isolation, mostly as a result of sport, they mainly occur in conjunction with other ligamentous injuries<ref>Schlumberger M, Schuster P, Eichinger M, Mayer P, Mayr R, Immendörfer M, Richter J. Posterior cruciate ligament lesions are mainly present as combined lesions even in sports injuries. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(7):2091-8. </ref> (see [[Multiligament Injured Knee Dislocation|multi-ligament knee injuries]]), usually caused by motor vehicle accidents.<ref name=":0">Schulz MS, Russe K, Weiler A, Eichhorn HJ, Strobel MJ. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00402-002-0471-y Epidemiology of posterior cruciate ligament injuries.] Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery 2003;123(4):186-91.</ref> PCL injuries account for 44%<ref>Fanelli GC. Posterior cruciate ligament injuries in trauma patients. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 1993 Jun 1;9(3):291-4.</ref> of acute knee injuries and most commonly present with posterolateral corner injury<ref name=":3">Wang D, Graziano J, Williams RJ, Jones KJ. Nonoperative Treatment of PCL Injuries: Goals of Rehabilitation and the Natural History of Conservative Care. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2018 Jun 1;11(2):290-7.</ref>. A 2-3% incidence is estimated for chronic, asymptomatic PCL insufficiency in elite college football players<ref>Parolie JM, Bergfeld JA. Long-term results of nonoperative treatment of isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries in the athlete. The American journal of sports medicine. 1986 Jan;14(1):35-8.</ref>. | ||

=== Aetiology/Mechanism of Injury === | |||

A 2% incidence is estimated for PCL | The most frequent mechanism of injury is a direct blow to the anterior aspect of the proximal tibia on a flexed knee with the [[Ankle Joint|ankle]] in plantarflexion<ref name=":0" />. This often occurs as dashboard injuries during motor vehicle accidents and results in posterior translation of the tibia. Hyper-extension and rotational or varus/valgus stress mechanisms may also be responsible for PCL tears.<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7">Lee BK, Nam SW. Rupture of Posterior Cruciate Ligament: Diagnosis and Treatment Principles. Knee Surgery and Related Research 2011 Sep;23(3):135-141.</ref><ref name="p6">American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Diseases & Conditions: Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. [http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00420 http://orthoi/nfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00420] (accessed 20/08/2018).</ref> These injuries occur mostly during sports such as football, soccer and skiing. Isolated PCL injuries are commonly reported in athletes, with hyper-flexion being the most frequent mechanism of injury.<ref name="p7" /><ref name="p8">Fowler PJ, Messieh SS. [http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/036354658701500606 Isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries in athletes.] The American Journal of Sports Medicine 1987;15(6):553–557.</ref> Athletes rarely report hearing a pop and may be able to continue to playing immediately after the injury<ref name=":3" />. Further mechanisms of PCL injury include bad landings from a jump, a simple misstep or fast direction change.<ref name="p7" /><ref name="p6" /> | ||

=== | |||

The most frequent mechanism of injury is a direct blow to the anterior aspect of the proximal tibia on a flexed knee with the [[Ankle Joint|ankle]] in plantarflexion<ref name=":0" />. This often occurs as dashboard injuries | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical presentation == | == Characteristics/Clinical presentation == | ||

| Line 36: | Line 32: | ||

=== Characteristics === | === Characteristics === | ||

PCL injuries present in different degrees according to the severity. | PCL injuries present in different degrees according to the severity. | ||

# '''Grade 1:''' Limited damage with only microscopic tears in the ligament, mostly as the result of an overstretch. It is still able to function and stabilize the knee.<ref name="p0">Malone AA, Dowd GSE, Saifuddin A. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S002013830500327X Injuries of the posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner of the knee.] Injury 2006;37(6):485-501.</ref> | |||

'''Grade 1:''' Limited damage with only microscopic tears in the ligament, mostly as the result of an overstretch. It is still able to function and stabilize the knee.<ref name="p0">Malone AA, Dowd GSE, Saifuddin A. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S002013830500327X Injuries of the posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner of the knee.] Injury 2006;37(6):485-501.</ref> | # '''Grade 2:'' ''''' The ligament is partially torn. There is a feeling of instability<ref name="p0" />. | ||

# '''Grade 3:'' '''''Complete ligament tear or rupture. This type of injury is mostly accompanied by a sprain of the ACL and/or collateral ligaments.<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p0" /><br> | |||

=== Clinical presentation === | === Clinical presentation === | ||

A distinction can be made between the symptoms of an acute and chronic PCL injury<ref name="p5">Bisson LJ, Clancy Jr WG. Chapter 90: Isolated posterior cruciate ligament injury and posterolateral laxity. In: Chapman’s Orthopaedic Surgery. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2001.</ref>. | A distinction can be made between the symptoms of an acute and chronic PCL injury<ref name="p5">Bisson LJ, Clancy Jr WG. Chapter 90: Isolated posterior cruciate ligament injury and posterolateral laxity. In: Chapman’s Orthopaedic Surgery. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2001.</ref>. | ||

==== Acute PCL injury ==== | ==== Acute PCL injury ==== | ||

| Line 69: | Line 66: | ||

=== Physical examination === | === Physical examination === | ||

A detailed history taking to understand the nature of symptoms and mechanism of injury to distinguish between different presentations. Weight bearing difficulty and reduced range of movement are the typical presentation. Ruling out fracture and dislocation will depend on symptoms and injury mechanism. | |||

* [[Posture]]: | * [[Posture]]: | ||

** Varus knee | ** Varus knee | ||

** External rotation recurvatum<ref name=":3" /> | |||

* [[Gait]]: | * [[Gait]]: | ||

** Varus thrust is indicative of instability<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7" /> | ** Varus thrust is indicative of instability<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7" /> | ||

| Line 80: | Line 79: | ||

=== Special tests === | === Special tests === | ||

* [[Posterior Drawer Test (Knee)|Posterior drawer]]: | * [[Posterior Drawer Test (Knee)|Posterior drawer]]: This test has the highest sensitivity and specificity of the clinical tests for assessing the PCL.<ref>Badri A, Gonzalez-Lomas G, Jazrawi L. Clinical and radiologic evaluation of the posterior cruciate ligament-injured knee. ''Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med''. 2018;11(3):515-20. </ref> It can only be executed when there is no swelling in the knee joint<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7" /> | ||

** PCL injury suspected if unable to palpate this one cm step-off or if the end-feel is soft when pushing the tibia posteriorly<ref name="p1" /> | ** PCL injury suspected if unable to palpate this one cm step-off or if the end-feel is soft when pushing the tibia posteriorly<ref name="p1" /> | ||

** > 10 mm posterior translation can indicate a posterolateral ligament complex injury<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7" /><br> | ** > 10 mm posterior translation can indicate a posterolateral ligament complex injury<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7" /><br> | ||

{{#ev:youtube| | {{#ev:youtube|HTti7-c1MFk}}<ref>Posterior Drawer test for PCL. Available from :https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HTti7-c1MFk</ref> | ||

* Posterior Lachman test: A slight increase in posterior translation indicates a posterolateral ligament complex injury<ref name="p2" /><ref name="p7" /> | * Posterior Lachman test: A slight increase in posterior translation indicates a posterolateral ligament complex injury<ref name="p2" /><ref name="p7" /> | ||

{{#ev:youtube| | {{#ev:youtube|l_bR0IrrgsE}}<ref>Lachman-Anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments test. Available from : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l_bR0IrrgsE</ref> | ||

* Posterior sag sign: Posterior sagging of the tibia indicates a positive test<ref name="p2" /><ref name="p7" /> | * Posterior sag sign: Posterior sagging of the tibia indicates a positive test<ref name="p2" /><ref name="p7" /> | ||

{{#ev:youtube| | {{#ev:youtube|kB__q4Y4lfA}}<ref>Posterior Sag Test. Avialble from : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kB__q4Y4lfA</ref> | ||

* Quadriceps active test<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7" /> | * Quadriceps active test<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7" />: this test can aid in the diagnosis of complete PCL tear<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":3" />. | ||

{{#ev:youtube| | {{#ev:youtube|5H0dALG6RR4}}<ref>Quadriceps Active Test. Availble from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5H0dALG6RR4</ref> | ||

* [[Dial Test|Dial test]] or tibial external rotation test | * [[Dial Test|Dial test]] or tibial external rotation test: to test if there is a combined PCL and posterolateral corner (PLC) injury.<ref>Norris R, Kopkow C, McNicholas MJ. Interpretations of the dial test should be reconsidered. A diagnostic accuracy study reporting sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and likelihood ratios. Journal of ISAKOS: Joint Disorders & Orthopaedic Sports Medicine 2018;3:198-204.</ref> Increased external rotation at 30 degrees only indicates an isolated PCL injury. Noticed differences at both 30 and 90 degrees indicate combined PCL and PLC injury<ref name=":3" />. | ||

{{#ev:youtube| | {{#ev:youtube|rnk62Y-nDSQ}}<ref>Dial Test (CR). Availble from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rnk62Y-nDSQ</ref> | ||

* Special tests to rule out concurrent knee injuries:<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p2" /><ref name="p7" /> | * Special tests to rule out concurrent knee injuries:<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p2" /><ref name="p7" /> | ||

** Varus/Valgus stress tests | ** Varus/Valgus stress tests | ||

** External rotation recurvatum test | ** External rotation recurvatum test | ||

** Reverse pivot shift test | ** Reverse pivot shift test | ||

{{#ev:youtube| | {{#ev:youtube|r-9CNXEzJpQ}}<ref>Reverse Pivot Shift Test. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r-9CNXEzJpQ</ref> | ||

=== Special investigations === | === Special investigations === | ||

| Line 104: | Line 103: | ||

** Assists in early identification of PCL avulsion fractures | ** Assists in early identification of PCL avulsion fractures | ||

** Chronic: Assess joint space narrowing (preferably including weight-bearing and sunrise views) | ** Chronic: Assess joint space narrowing (preferably including weight-bearing and sunrise views) | ||

* '''[[MRI Scans|MRI]]:''' | * '''[[MRI Scans|MRI]]: the gold standard when it comes to diagnosing PCL and associated injuries'''<ref name=":3" /> | ||

** Acute: Determine grade of injury, as well as evaluating other potentially injured structures (e.g. ligaments, meniscus and/or cartilage structures of the knee) | ** Acute: Determine grade of injury, as well as evaluating other potentially injured structures (e.g. ligaments, meniscus and/or cartilage structures of the knee). An increased signal or disrupted continuity of the ligament is expected<ref name=":3" />. | ||

** Chronic: MRI may appear normal in grade I and II injures | ** Chronic: MRI may appear normal in grade I and II injures. | ||

* '''Bone scans:''' Best in chronic cases with pain and instability. | * '''Bone scans:''' Best in chronic cases with recurrent pain, swelling and instability. | ||

** Detect early arthritic changes before MRI or | ** Detect early arthritic changes before MRI or X-ray. These patients have a higher risk of developing articular cartilage degenerative changes, shown by areas of increased radiotracer uptake, most commonly in the medial and patellofemoral compartments. | ||

* '''[[Ultrasound Scans|Ultrasound]]:''' More cost effective than MRI for evaluation | * '''[[Ultrasound Scans|Ultrasound]]:''' More cost effective than MRI for evaluation | ||

* '''Arteriogram:''' Evaluate the vascular status in the limb | * '''Arteriogram:''' Evaluate the vascular status in the limb | ||

<ref name="p8" /><ref name="p9">Wind WM, Jr, Bergfeld JA, Parker RD. [http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0363546504270481 Evaluation and treatment of posterior cruciate ligament injuries: revisited.] The American Journal of Sports Medecine 2004, 32(7):1765–1775.</ref> | <ref name="p8" /><ref name="p9">Wind WM, Jr, Bergfeld JA, Parker RD. [http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0363546504270481 Evaluation and treatment of posterior cruciate ligament injuries: revisited.] The American Journal of Sports Medecine 2004, 32(7):1765–1775.</ref> | ||

== Outcome measures == | == Outcome measures<ref name="p9" /> == | ||

* Noyes knee score Questionnaire | * Noyes knee score Questionnaire | ||

* [http://www.lakarhuset.com/docs/lysholmkneescoringscale.pdf Lysholm score] | * [http://www.lakarhuset.com/docs/lysholmkneescoringscale.pdf Lysholm score] | ||

| Line 120: | Line 118: | ||

* Multiligament Quality of Life questionnaire | * Multiligament Quality of Life questionnaire | ||

* [https://www.hss.edu/secure/files/WSMC-ikdc.pdf International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form] | * [https://www.hss.edu/secure/files/WSMC-ikdc.pdf International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form] | ||

== Medical management == | == Medical management == | ||

=== | === Conservative management === | ||

Non-operative treatment | Non-operative treatment of isolated PCL injuries has been shown to result in good subjective outcomes, as well as high rates of return to sport.<ref>Wang D, Graziano J, Williams RJ 3rd, Jones KJ. Nonoperative Treatment of PCL Injuries: Goals of Rehabilitation and the Natural History of Conservative Care. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018;11(2):290-7. </ref> This approach is normally used for an acute, isolated grade I or II PCL sprains, if they fit the following criteria:<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p6" /><ref name="p9" /> | ||

* Posterior drawer <10 mm | * [[Posterior Drawer Test (Knee)|Posterior drawer]] <10 mm | ||

* Decrease in posterior drawer excursion with internal rotation on the femur | * Decrease in posterior drawer excursion with internal rotation on the femur | ||

* <5° abnormal rotary laxity and/or no significant increased valgus-varus laxity | * <5° abnormal rotary laxity and/or no significant increased valgus-varus laxity | ||

Management | Grade I and II PCL tears usually recover rapidly and most patients are satisfied with the outcome. Athletes are normally ready for return to play within 2-4 weeks.<ref name="p8" /><ref name="p9" /> Management includes:<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p9" /><ref name=":2" /> | ||

* | * Immobilise the knee in a range of motion brace locked in extension for 2-3 weeks | ||

* Assisted weight-bearing (partial to full) for 2 | * Assisted weight-bearing (partial to full) for 2 weeks | ||

* Physiotherapy | * Physiotherapy | ||

An acute grade III injury can also be managed conservatively. Immobilisation in a range of motion brace in full extension is recommended for two to four weeks, due to the high probability of injuries to other posterolateral structures. The posterior tibial sublaxation caused by the hamstring is minimised in extension, causing less force to the damaged PCL and posterolateral structures.<ref name="p8" /><ref name="p9" /> This allows the soft tissue structures to heal. Physiotherapy is recommended as part of the conservative management.<ref name="p1" /> Return to play after conservative management of grade III tears is normally between 3 and 4 months.<ref name="p8" /><ref name="p9" /> | |||

Chronic isolated grade I & II PCL injuries are usually managed conservatively with physiotherapy. Activity modification is recommended in chronic cases with recurrent pain and swelling.<ref name="p1" /> | Chronic isolated grade I & II PCL injuries are usually managed conservatively with physiotherapy. Activity modification is recommended in chronic cases with recurrent pain and swelling.<ref name="p1" /> | ||

=== Surgical management === | |||

The primary objective during a PCL reconstruction is to restore normal knee mechanics and dynamic knee stability, thus correcting posterior tibial laxity.<ref name="p8" /><ref name="p9" /> There are different options of the optimal surgical approach for a PCL reconstruction. Debate exists about the best graft type or source, placement of the tibia, femoral tunnels, number of graft bundles and the amount of tension on the bundles.<ref name="p8" /> | |||

When using a double bundle graft, both bundles of the PCL can be reconstructed. A single bundle graft reconstructs only the stronger anterolateral bundle. The double bundle approach can restore normal knee kinematics with a full range of motion, while the single bundle only restores the 0°-60° knee range.<ref name="p9" /> | |||

Types of grafts include:<ref name="p8" /> | |||

* Allograft (mostly [[Achilles Tendon]]): Decreased surgical time and the absence of iatrogenic trauma to the harvest site. The Achilles tendon graft produces a large amount of collagen and ensures a complete filling of the tunnels. This is normally used to reconstruct the AL bundle. The AL graft is tensioned and fixed at 90° knee flexion.<ref name="p9" /> | |||

* Autologous tissue: | |||

** Bone-patellar tendon-bone: Most common, as the bone plugs allow sufficient fixation of the tissue. The disadvantages of this graft are the harvest site morbidity and as a result of the rectangular form of the graft, the tunnels can not be completely filled with collagen. | |||

** Quadrupled hamstring: Decreases the morbidity factor, but results in an inferior fixation method. A double semitendinosus tendon autograft is normally used for the PM bundle reconstruction. The PM graft is tensioned and fixed at 30° knee flexion. | |||

** Quadriceps tendon: Has morbidity factor and adequate biomechanical properties.<br> | |||

==== Acute PCL injury ==== | ==== Acute PCL injury ==== | ||

PCL avulsion fracture injuries fractures heal well when operated early on.<ref name="p8" /><ref name="p9" /> High demand individuals, such as young athletes, are normally treated with surgery as soon as possible, to enhance the chances to return to full functional capacity | Surgical reconstruction of the PCL is recommended in acute injuries with severe posterior tibia subluxation and instability, if the posterior translation is greater than 10mm or if there are multiple ligamentous injuries. PCL avulsion fracture injuries fractures heal well when operated early on.<ref name="p8" /><ref name="p9" /> High demand individuals, such as young athletes, are normally treated with surgery as soon as possible, to enhance the chances to return to full functional capacity.<ref name=":2" /> Grade III injury of the PCL are mostly combined with other injuries, and thus surgical reconstruction of the ligaments will have to be done, often within 2 weeks from the injury. This time frame gives the best anatomical ligament repair of the PCL and less capsular scarring. | ||

==== Chronic PCL injury ==== | ==== Chronic PCL injury ==== | ||

Surgical intervention are recommended in chronic cases, considering the following (mostly in grade III injuries):<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p9" /> | Surgical intervention are recommended in chronic cases, considering the following (mostly in grade III injuries):<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p9" /> | ||

* Recurrent pain and swelling | * Recurrent pain and swelling | ||

* Positive bone scan | * Positive bone scan with the patient being unable to modify his/her activities | ||

* | * In cases where combination injuries are present, surgery is indispensable | ||

==== Surgical procedure ==== | |||

* '''Tibial inlay procedure''': Starts with a diagnostic arthroscopy, but the inlay itself is an open surgery. The femoral tunnels are established with an outside-in technique to closely duplicate the femoral insertion of the PCL-meniscofemoral ligament complex. The graft is prepared during the exposure. Then it is placed in the graft passer and passed through the femoral tunnel, tensioned and screwed to the bone. | |||

** Limiting knee range of motion bracing is needed after the surgery (see ''physiotherapy management''). | |||

* '''Tibial tunnel method:''' Arthroscopical approach. A guide pin is drilled from a point just distal and medial to the tibial tubercle and aimed at the distal and lateral aspect of the PCL footprint. The femoral tunnel should be placed just under the subchondral bone, to reduce the risk of osteonecrosis. The direction of the graft passage depends on the type of graft used. The tibial inlay procedure avoids this difficult part. The graft is placed in 70° to 90° flexion. In the single bundle reconstruction only 1 tunnel is drilled. In a double-bundle reconstruction two tunnels are drilled, which is technically more challenging.<ref name="p8" /><ref name="p9" /> | |||

==== Complications ==== | |||

Possible complications after or during a PCL reconstruction include:<ref name="p8" /> | |||

* Fractures | |||

* Popliteal artery injury | |||

* [[Deep Vein Thrombosis|Deep vein thrombosis]] | |||

* Residual laxity (can be caused by an undiagnosed non-isolated PCL injury) | |||

* Decrease range of motion (can be caused by improper placement or too much tension of the graft). | |||

** Manipulation under anaesthesia can be considered to improve range of motion if physiotherapy is unsuccessful | |||

== Medical Management Biomechanics == | |||

=== Bundle Reconstruction or Conservative Management === | |||

The [[Posterior Cruciate Ligament]]’s primary function in the knee is to prevent posterior translation of the tibia on the femur. It consists of 2 main bundles: the anterolateral bundle (ALB) and posteromedial bundle (PMB). These parts work together to provide full protection in all degrees of flexion and pivoting. The ALB prevents external rotation, and the PMB prevents internal rotation. Together, they prevent anteroposterior translation through a codominant relationship. Their mediolateral components are valuable in protecting the knee from rotational forces in different degrees of flexion. The ALB is taut in flexion, and the PMB is taut in extension <ref>Jakobsen RB, Jakobsen BW. Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. Evidence-Based Orthop. 2011;822–31. </ref><ref>Lee YS, Jung YB. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3858094/ Posterior cruciate ligament: Focus on conflicting issues]. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013;5(4):256–62. </ref><ref name=":4">Trasolini NA, Lindsay A, Gipsman A, Rick Hatch GF. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30878045/ The Biomechanics of Multiligament Knee Injuries: From Trauma to Treatment.] Clin Sports Med. 2019;38(2):215–34. </ref>. Although the tension differs at different degrees of flexion, their codominant relationship is put into effect based on their spatial orientation. With increased flexion, the ALB it taut and more vertically aligned. Due to this orientation, it is less able to resist posterior translation. However, the greater the flexion of the knee, the more horizontally oriented the PMB becomes, thus increasing its ability to resist posterior translation<ref name=":5">Voos JE, Mauro CS, Wente T, Warren RF, Wickiewicz TL. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21803977/ Posterior cruciate ligament: Anatomy, biomechanics, and outcomes]. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(1):222–31. </ref>. | |||

A tear or stretch will occur when the external force exceeds the capabilities of these tendons. The most common mechanism of injury is in a motor vehicle accident called the “dashboard injury”, where the tibia is forced into posterior translation on the femur. This often results in a [[Multiligament Injured Knee Dislocation|multi-ligament injury]] and commonly require surgical intervention <ref name=":4" />, but there are instances of acute injury as well. Low grade acute injuries are dealt with conservative treatment. | |||

==== '''Conservative Treatment''' ==== | |||

Conservative treatment has been a common choice for PCL tear rehabilitation especially in grade I and II acute tears due to the ligaments strong intrinsic ability to heal <ref>Grassmayr MJ, Parker DA, Coolican MRJ, Vanwanseele B. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17884727/ Posterior cruciate ligament deficiency: Biomechanical and biological consequences and the outcomes of conservative treatment. A systematic review]. J Sci Med Sport. 2008;11(5):433–43. </ref><ref name=":6">Pierce CM, O’Brien L, Griffin LW, LaPrade RF. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22484415/ Posterior cruciate ligament tears: Functional and postoperative rehabilitation.] Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(5):1071–84. </ref><ref name=":7">Pache S, Aman ZS, Kennedy M, Nakama GY, Moatshe G, Ziegler C, et al. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5799606/ Posterior cruciate ligament: Current concepts review.] Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2018;6(1):8–18. </ref>. During conservative treatment, the general rehab program would focus on building weight bearing capabilities and quadriceps strengthening<ref name=":6" />. The initial stage of healing focuses on maintaining range of motion and decreasing swelling and edema while protecting the PCL. To protect the PCL in later stages of healing, quadricep training begins, and hamstring exercises are avoided. The function of the [[Quadriceps Muscle|quadriceps]] is to extend the knee, and due to its attachment site on the anterior side of the base of the tibial plateau; its accessory motion pulls the tibia forward on the femur when extending the knee pulling in the opposite direction of the PCL’s function. In contrast, [[Hamstrings]] are responsible for flexion of the knee, and would increase posterior sheer force from the tibia thus stressing or re-tearing a healing PCL. Walking is often included early in the rehab stages with a dynamic brace that allows for knee flexion but supports the tibia posteriorly. | |||

The conservative treatments also apply to the post-operative protocol in patients for reconstruction, but they are usually shorter in duration<ref name=":6" />. | |||

Some studies have found negative long-term effects in the PCL with conservative treatment such as a higher degree of laxity and more incidences of degenerative changes in medial and [[Patellofemoral Joint|patellofemoral]] compartments. Increased laxity means that the PCL is not taut in places where it should be, and the femur will translate farther especially in the posterior direction. The imbalance impacts the articular cartilage, and there is an increased amount of shear and compression forces on the tibial plateau. Over time, the articular cartilage degenerates, leading to an increased incidence of [[osteoarthritis]] and [[Meniscal Lesions|meniscal tears]]. Structures in the posterolateral corner are also at an increased risk of injury with a deficient PCL. The laxity changes the kinematics and loads on the knee during functional activities. In one study, a single legged lunge was performed with fluoroscopy in a person with a lax PCL and a person with an intact PCL. The results showed an increase in cartilage deformation on the tibia in the PCL-deficient knee<ref name=":5" /> indicating a change in tibiofemoral mechanics as well. | |||

==== '''Single Bundle Reconstruction''' ==== | |||

When the tear is Grade II or higher it may require [[PCL Reconstruction|reconstruction]] surgery. The Single Bundle Reconstruction (SBR) recreates the largest and stronger bundle of the two – The ALB. The ALB is the stronger bundle and is the primary restraint to posterior translation. The ultimate load failure of the ALB is nearly double that of the PMB: 1120± 362 N and 419±128 N respectively<ref name=":8">Johnson P, Mitchell SM, Görtz S. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6105491/ Graft Considerations in Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction.] 2018;521–7. </ref>. For the most people, this treatment has been good enough and allows them to continue their activities as before. However, without the two bundles, they do not have as much support in full flexion when compared to a double bundle reconstruction. SBR provides full anteroposterior support from 0-60° of flexion<ref>Qi Y, Wang H, Wang S, Zhang Z, Huang A, Yu J. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4730768/ A systematic review of double-bundle versus single-bundle posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.] BMC Musculoskelet Disord [Internet]. 2016;1–9. Available from: <nowiki>http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-0896-z</nowiki></ref>. Most people do not require that much flexion in everyday activities. | |||

SBR has some issues in the long term; many follow up studies show persistent posterior laxity of the knee and increased patellar femoral pressure<ref>Grotting JA, Nelson TJ, Banffy MB, Yalamanchili D, Eberlein SA, Chahla J, et al. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32014412/ The Knee Biomechanical evaluation of PCL reconstruction with suture augmentation]. Knee [Internet]. 2020;27(2):375–83. Available from: <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2020.01.004</nowiki></ref>. This laxity means that the femur will move less predictably along the tibial plateau, increasing the risk of osteoarthritis and posterolateral corner injuries due to increased pressure<ref name=":8" />. | |||

==== '''Double Bundle Reconstruction''' ==== | |||

Double Bundle Reconstruction (DBR) is a relatively new method, and it attempts to better recreate the native PCL with the ALB and PMB. There is evidence that this method better recreates their codominant relationship thus restores the knee to greater stability for resisting posterior tibial translation than SBR<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":9">Wijdicks CA, Kennedy NI, Goldsmith MT, Devitt BM, Michalski MP, Årøen A, et al. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24092043/ Kinematic analysis of the posterior cruciate ligament, Part 2: A comparison of anatomic single- Versus double-bundle reconstruction]. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(12):2839–48. </ref><ref name=":10">Dornan GJ, Sc M, Mitchell JJ, Ridley TJ, Laprade RF, Ph D. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28866340/ Single-Bundle and Double-Bundle Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of 441 Patients at a Minimum 2&nbsp;Years’ Follow-up.] Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg [Internet]. 2017;33(11):2066–80. Available from: <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2017.06.049</nowiki></ref>. Some studies show that it has less posterior laxity when compared to SBR and conservative treatment because of the codominant relationship<ref name=":8" />. In a randomized control trial comparing allografts of SBR and DBR, they found that DBR had better result in terms of laxity than the SBR. This was tested with subjective tests (International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC)), Subjective Knee Form, Lysholm Score, Tegner Activity Scale) and objective tests (reduced knee laxity)<ref>Winkler PW, Zsidai B, Wagala NN, Hughes JD, Horvath A, Senorski EH, et al. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7917042/ Evolving evidence in the treatment of primary and recurrent posterior cruciate ligament injuries, part 2: surgical techniques, outcomes and rehabilitation]. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc [Internet]. 2020;29(3):682–93. Available from: <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06337-2</nowiki></ref>. | |||

The | DBR was also better than SBR when comparing their posterior tibial translation. Tested under 134N of posterior tibial load at 30°, 45°, 60°, 75°, 90°, 105°, and 120° of flexion, DBR had significantly less posterior tibial translation than SBR. The most significant difference was at 105° of flexion, where the SBR knee had 5.3 mm more translation than the DBR. When compared to an intact knee from 0° to 15° of flexion, DBR had more posterior tibial translation <ref name=":9" />. This shows that the DBR method does not fully recreate the kinematics of a native knee. In addition, The DBR was superior when comparing to the SBR regarding rotational resistance<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":9" />. | ||

Clinical and patient reported outcomes have not had any significant differences between DBR and SBR<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":10" />. However, most patient outcomes are only comparing their post-op to their injured status, not their pre-injury status. This would be an area to focus further research on. | |||

==== '''Conclusion''' ==== | |||

The DBR provides more biomechanical support which leads to fewer negative outcomes in the long term than SBR or the conservative treatment. DBRs are usually considered for high performance athletes because they may need the stability in all degrees of flexion. However, based on findings in biomechanical studies, DBR should be considered as a treatment method for an average person. There are some reasons why DBR may not be considered, for example, if bone density is too low then it might not be safe to create the tunnels in the tibia for the graft’s attachments. People with low bone density or [[osteoporosis]] would be safer with SBR or conservative treatment, as fewer tunnels reduce [[fracture]] risk in this group. | |||

It is important to know that neither method, SBR or DBR fully recreated native knee kinematics, and there is no current agreement on which method is better. The disagreement arises from the variability in other aspects of a PCL reconstruction such as graft type, graft tension, angle of implementation, graft tensioning, and surgical technique (tibial inlay and trans-tibial). Future studies should compare knees under similar conditions with larger sample sizes for the best results. However, it would still be difficult to understand the clinical outcomes because it is difficult to compare to a pre-injury or pre-laxity status. | |||

Conservative treatment methods are also very effective in post-op to decrease future risk of injury and to reduce residual laxity long-term. Knee immobilization for 3 days before moving to a dynamic knee brace and progressive weight bearing, avoiding hyperextension, and strengthening the quadriceps are the common post-op methods<ref name=":7" />. and recommended for quick recovery | |||

== Physiotherapy management == | |||

=== Conservative management === | |||

==== Grade 1 & II injuries ==== | |||

Two weeks of relative immobilisation of the knee (in a locked range of motion brace) is recommended by orthopaedic surgeons. Physiotherapy in this time period includes:<ref name="p1" /><ref name="p7" /><ref name="p8" /><ref name="p9" /> | |||

* Partial to full weight-bearing mobilisation | |||

* Reduce pain and inflammation | |||

* Reducing knee joint effusion | |||

* Restore knee range of motion | |||

* Knee strengthening (especially protective quadriceps rehabilitation) | |||

** Strengthening the quadriceps is a key factor in a successful recovery, as the quadriceps can take the place of the PCL to a certain extent to prevent the femur from moving too far forward over the tibia. | |||

** Hamstring strengthening can be included | |||

** Important to incorporate eccentric strengthening of the lower limb muscles | |||

** Closed chain exercises | |||

* Activity modification until pain and swelling subsides | |||

After 2 weeks (on the orthopaedic surgeon's recommendation):<ref name="p7" /> | |||

* Progress to full weight-bearing mobilisation | |||

* Weaning of range of motion brace | |||

* [[Proprioception]], [[balance]] and [[Coordination Exercises|coordination]] | |||

* Agility programme when strength and endurance has been regained and the neuromuscular control increased | |||

* Return to play between 2 and 4 weeks of injury | |||

==== Grade III injuries ==== | |||

The knee is immobilised in range of motion brace, locked in extension, for 2-4 weeks. Physiotherapy management in this time includes: | |||

* Activity modification | |||

* Quadriceps rehabilitation | |||

** Initially isometric quadriceps exercises and straight-leg raises (SLR) | |||

After 2-4 weeks:<ref name="p7" /><ref name="p8" /> | |||

* Avoid isolated hamstring strengthening | |||

* Active-assisted knee flexion <70° | |||

* Progress weight-bearing within pain limits | |||

* Quadriceps rehabilitation: Promote dynamic stabilisation and counteract posterior tibial subluxation | |||

** Closed chain exercises | |||

** [[Open Chain Exercise|Open kinetic chain]] eccentric exercises and eventually | |||

** Progress to functional exercises such as stationary cycling, leg press, elliptical exercises and stair climbing | |||

Return to play is sport specific, and only after 3 months.<ref name="p7" /><br> | |||

==== Chronic injuries ==== | |||

Chronic PCL injuries can be adequately treated with physiotherapy. A range of motion brace is used, initially set to prevent the terminal 15° of extension. After a while the brace is opened to full extension.<ref name="p9" /> | |||

=== Post-operative rehabilitation === | |||

Post-operative rehabilitation typically lasts 6 to 9 months. The duration of each of the five phases and the total duration of the rehabilitation depends on the age and physical level of the patient, as well as the success of the operation. Also see page on [[PCL Reconstruction|PCL reconstruction]]. | |||

'''General Guidelines for the post-operative PCL rehabilitation:''' | |||

* Mobility should be restricted from 0-90 degrees in the first two weeks then facilitated gradually to full ROM. | |||

* Involved leg should be in non-weight bearing for the first 6 weeks then placed in mobilizer brace and progressed to rebound PCL brace for 6 months. | |||

* Avoid isolated hamstrings contraction for 4 months due to the hamstrings force in drawing tibia posteriorly which can apply an elongation force on the PCL graft causing instability | |||

* Avoid unsupported knee flexion for 4 months to prevent any posterior drawing forces on tibia. | |||

Post-operative | ==== Phase I: Early Post-operative phase ==== | ||

Early mobilisation and placing sub-maximal strain on graft lead to better outcomes<ref>Senese M, Greenberg E, Lawrence JT, Ganley T. Rehabilitation following isolated posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a literature review of published protocols. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2018 Aug;13(4):737.</ref>. | |||

'''Objectives of maximal protection and early rehabilitation:''' | |||

* Restore joint homeostasis | |||

* Scar tissue management | |||

* Restore joint ROM | |||

* Re-train quadriceps | |||

* Create an effective plan for your patient | |||

'''Strategies of rehabilitation:''' | |||

* Perform ROM exercises from prone position to avoid posterior tibial sag and graft elongation | |||

* Teach patient to perform Quadriceps contraction/sets from day 1 post surgery if the patient is not on strong pain medications. | |||

* Patellofemoral mobilisation is important to prevent scarring and preserve joint volume for full range of flexion and extension | |||

* Ice and elevation for swelling and inflammation management | |||

* Progressing by applying strategies for increasing ROM and terminal knee extension | |||

One of the huge advancement of PCL management is the utilisation of Dynamic PCL braces. This option may not always be available but if found make sure to utilise it. It's a spring loaded brace aiming to place an anterior force on the tibia preventing posterior tibial sag and graft elongation by placing the graft in a shortened position. Immediately after surgery, it is recommended to place the leg in a mobiliser braces then progress to a dynamic brace once swelling is subsided. It should be used all the time and only taken off to perform exercises for 6 months. Then move into more functional bracing, worn all the time for 12 months. | |||

{{#ev:youtube|2gglMSyM4i4}}<ref>Rebound® PCL : Practitioner Fitting . Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2gglMSyM4i4 </ref> | |||

Building weight bearing tolerance after 6 weeks of non weight bearing (NWB) should take place gradually and progressively between week 7-8 . | |||

==== Phase II: Later Post-operative Rehabilitation ==== | |||

Begins 8 weeks after surgery. The aim is to create a plan for the patient to prepare them for returning to pre-operative functional capacity by addressing all MSK deficits. | |||

Areas to address in late post-operative rehabilitation and suggested time-frames: | |||

* Muscular endurance (weeks:9-16) | |||

* Strength (weeks 17-22) | |||

* Power (weeks 23-28) with running progression if it needed (weeks 25-28) | |||

* Speed and agility (weeks 29-32 ) | |||

* Return to training (week 33). | |||

* Return to sport : It varies from a sport to another but on average takes about with 3-4 weeks of training. Return to play around 36th week. | |||

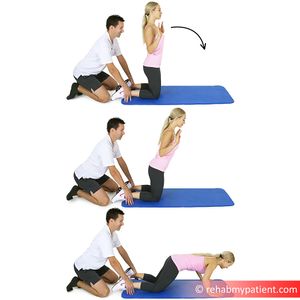

There are no specific exercises for PCL rehabilitation but generally we should think about the entire leg after a period of NWB. Incorporate different exercises for Quadriceps, gluteals and hamstrings and combine them in functional exercises. Adjust training parameters to targeted goal; endurance, power or strengthening. | |||

Examples of exercises: | |||

would look like | |||

{| cellpadding="1" cellspacing="1" border="1" | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | Muscle | |||

! scope="col" | Example | |||

! scope="col" | | |||

|- | |||

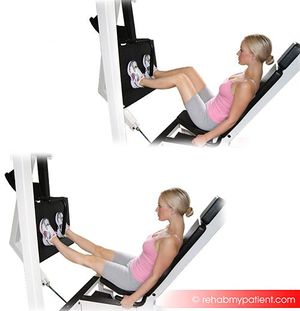

| Quadriceps Dominant | |||

| Leg Press | |||

| [[File:Leg Press.jpg|none|thumb]] | |||

|- | |||

| Glutes Dominant | |||

| Single Leg Bridge | |||

| [[File:Single leg extension from bridge.jpg|none|thumb]] | |||

|- | |||

| Hamstrings Dominant | |||

| Romanian Deadlift | |||

|[[File:Single leg dead lift.jpg|none|thumb]] | |||

|- | |||

| Quadriceps Dominant | |||

| Tuck Squat | |||

| [[File:Tuck squat.jpg|none|thumb]] | |||

|- | |||

| Quadriceps Dominant | |||

| Single Leg Squat | |||

| [[File:Single leg squat.gif|none|thumb]] | |||

|- | |||

| Hamstrings Dominant | |||

| Hamstrings Lean/Nordic Hamstrings Curl | |||

|[[File:Nordic hamstring curl.jpg|none|thumb]] | |||

|} | |||

==== Return to Sport Criteria: ==== | |||

the evidence hasn't provided specific criteria for return to sport following PCL reconstruction but logically we can adapt the same criteria after ACL reconstruction<ref>Barber-Westin SD, Noyes FR. [https://www.arthroscopyjournal.org/article/S0749-8063(11)01125-X/fulltext Factors used to determine return to unrestricted sports activities after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.] Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 2011;27(12):1697-705.</ref>: | |||

* | * A Quad index of 90 or more- less than 10% deficits in quadriceps strength between involved and non-involved side. Hamstrings strength should also be considered. | ||

* | * Less than 15% deficit in lower limb symmetry on single-leg hop testing (single hop, triple hop, crossover hop, and timed hop) | ||

< | {{#ev:youtube|4Rp_BJUBQ6g}}<ref>Triple hop for distance. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Rp_BJUBQ6g</ref> | ||

== Clinical bottom line == | == Clinical bottom line == | ||

PCL injuries do not occur frequently. | PCL injuries are mostly caused by hyper-flexion and injuries do not occur frequently. This is due to the strength of the ligament and the fact that hyper-flexion, possible through a force to the anterior aspect of the proximal tibia, does not commonly occur. PCL injuries will mostly happen during sports, such as football, soccer and skiing. Another possible mechanism of injury can be a car accident, resulting in a 'dashboard injury'. The severity is divided in three degrees and an acute injury is distinguished from a chronic injury. Clinical presentation will depend on the degree and the condition of the injury. If symptoms are observable, these usually include swelling, pain, a feeling of instability, limited range of motion and difficulty with mobilisation. The treatment depends on the grade and the individual patient. A grade I and II injury are usually treated non-surgically, unless it occurs in an young athlete or high demand individual. A grade III injury is usually treated by a surgical intervention, however non-surgical treatment is also possible. Physiotherapy plays a role in conservative management, as well as post-operative rehabilitation. Both rehabilitation programs focus on the quadriceps muscle group, because of its ability to partially take over the function of the PCL. The structure and the build-up of the rehabilitation program depends on the degree of the injury, the individual patient and the success of the operation (if applicable). | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| Line 276: | Line 348: | ||

[[Category:Knee_Injuries]] | [[Category:Knee_Injuries]] | ||

[[Category:Knee]] | [[Category:Knee]] | ||

[[Category:Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Knee - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Ligaments]] | [[Category:Ligaments]] | ||

[[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics|Orthopaedics]] | [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics|Orthopaedics]] | ||

| Line 282: | Line 357: | ||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | [[Category:Sports Medicine]] | ||

[[Category:Primary Contact]] | [[Category:Primary Contact]] | ||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

[[Category:Plus Content]] | |||

Latest revision as of 18:52, 1 November 2022

Original Editors - Sigrid Bortels Top Contributors - Camille Dewaele, Sigrid Bortels, Leana Louw, Mariam Hashem, Kim Jackson, Admin, Kai A. Sigel, Rachael Lowe, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Vanderpooten Willem, Fasuba Ayobami, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Wanda van Niekerk, Hana Vezsenyi, Daphne Jackson, Claire Knott, Jess Bell, Robin Tacchetti, Evan Thomas, Oyemi Sillo and Naomi O'Reilly

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The most powerful ligament in the knee joint is the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).[1] The role of the PCL is to prevent the tibia from moving backwards relative to the femur.[2]Injuries to the PCL often occur with other knee structures (ligaments, meniscus) while infrequently occurring in isolation. [3]PCL injury alone accounts for approximately 2 per 100,000 people annually. [4]

Injury to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) can range from a stretch to a total tear or rupture of the ligament. These injuries are relatively uncommon.[5] They occur less frequently than anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries as the PCL is broader and stronger.[6]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The PCL is one of the two cruciate ligaments of the knee. It acts as the major stabilising ligament of the knee. and prevents the tibia from excessive posterior displacement in relation to the femur. It also functions to prevent hyper-extension and limits internal rotation, adduction and abduction at the knee joint.[6] The PCL is twice as thick as the ACL which results in less injuries than the ACL due to the stronger nature. As a result, PCL injuries are less common than ACL injuries.

It originates at the internal surface of the medial femoral condyle and inserts on the centre of the posterior aspect of the tibial plateau, 1 cm below the articular surface of the tibia[6][7]. It crosses the ACL to form an 'X'. The PCL consists of two inseparable bundles: the wide anterolateral (AL) bundle and the smaller posteromedial (PM) bundle.[6] The AL bundle is most tight in mid-flexion and internal rotation of the knee, while the PM bundle is most tight in extension and deep flexion of the knee. The orientation of the fibres varies between bundles. The AL bundle is more horizontally orientated in extension and becomes more vertical as the knee is flexed beyond 30°. The PM bundle is vertically orientated in knee extension and becomes more horizontal through a similar range of motion.[6][7]

Epidemiology/Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The mean age of people with acute PCL injuries range between 20-30's. While injuries to the PCL can occur in isolation, mostly as a result of sport, they mainly occur in conjunction with other ligamentous injuries[8] (see multi-ligament knee injuries), usually caused by motor vehicle accidents.[9] PCL injuries account for 44%[10] of acute knee injuries and most commonly present with posterolateral corner injury[11]. A 2-3% incidence is estimated for chronic, asymptomatic PCL insufficiency in elite college football players[12].

Aetiology/Mechanism of Injury[edit | edit source]

The most frequent mechanism of injury is a direct blow to the anterior aspect of the proximal tibia on a flexed knee with the ankle in plantarflexion[9]. This often occurs as dashboard injuries during motor vehicle accidents and results in posterior translation of the tibia. Hyper-extension and rotational or varus/valgus stress mechanisms may also be responsible for PCL tears.[6][13][14] These injuries occur mostly during sports such as football, soccer and skiing. Isolated PCL injuries are commonly reported in athletes, with hyper-flexion being the most frequent mechanism of injury.[13][15] Athletes rarely report hearing a pop and may be able to continue to playing immediately after the injury[11]. Further mechanisms of PCL injury include bad landings from a jump, a simple misstep or fast direction change.[13][14]

Characteristics/Clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

Characteristics[edit | edit source]

PCL injuries present in different degrees according to the severity.

- Grade 1: Limited damage with only microscopic tears in the ligament, mostly as the result of an overstretch. It is still able to function and stabilize the knee.[16]

- Grade 2: The ligament is partially torn. There is a feeling of instability[16].

- Grade 3: Complete ligament tear or rupture. This type of injury is mostly accompanied by a sprain of the ACL and/or collateral ligaments.[6][16]

Clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

A distinction can be made between the symptoms of an acute and chronic PCL injury[17].

Acute PCL injury[edit | edit source]

- Isolated injury:

Symptoms are often vague and minimal, with patients often not even feeling or noticing the injury.[6][7][17] Minimal pain, swelling, instability and full range of motion is present, as well as a near-normal gait pattern.[6][7][17]

- Combination with other ligamentous injuries:

Symptoms differ according to the extent of the knee injury. This includes swelling, pain, a feeling of instability, limited range of motion and difficulty with mobilisation. Bruising may also be present.[6]

Chronic PCL injury[edit | edit source]

Patients with a chronic PCL injury are not always able to recall a mechanism of injury. Common complaints are discomfort with weight-bearing in a semi flexed position (e.g. climbing stairs or squatting) and aching in the knee when walking long distances. Complaints of instability are also often present, mostly when walking on an uneven surface[17]. Retropatellar pain and pain in the medial compartment of the knee may also be present[17]. Potential swelling and stiffness depend on the degree of associated chondral damage.[17]

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- ACL injury

- Medial collateral ligament injury

- Talofibular ligament injury

- Menisci injuries

- Patellofemoral joint injuries

- Posterolateral knee injury and associated varus instability

Uncommon:[18]

- Multiligament knee injury

- Femoral condyle fracture

- Tibial plateau fracture

Diagnostic procedures[edit | edit source]

Physical examination[edit | edit source]

A detailed history taking to understand the nature of symptoms and mechanism of injury to distinguish between different presentations. Weight bearing difficulty and reduced range of movement are the typical presentation. Ruling out fracture and dislocation will depend on symptoms and injury mechanism.

- Neurovascular examination to rule out concurrent injuries[19]

- Palpation: Minimum/no swelling in isolated injury [20]

- Muscle power

- Range of motion

Special tests[edit | edit source]

- Posterior drawer: This test has the highest sensitivity and specificity of the clinical tests for assessing the PCL.[21] It can only be executed when there is no swelling in the knee joint[6][13]

- Posterior Lachman test: A slight increase in posterior translation indicates a posterolateral ligament complex injury[7][13]

- Dial test or tibial external rotation test: to test if there is a combined PCL and posterolateral corner (PLC) injury.[26] Increased external rotation at 30 degrees only indicates an isolated PCL injury. Noticed differences at both 30 and 90 degrees indicate combined PCL and PLC injury[11].

- Special tests to rule out concurrent knee injuries:[6][7][13]

- Varus/Valgus stress tests

- External rotation recurvatum test

- Reverse pivot shift test

Special investigations[edit | edit source]

- X-rays:

- AP, tunnel, sunrise, stress and a lateral views (best to detect lateral sag)

- X-rays can be done in different positions, e.g. standing and weight-bearing with 45° knee flexion

- Assists in early identification of PCL avulsion fractures

- Chronic: Assess joint space narrowing (preferably including weight-bearing and sunrise views)

- MRI: the gold standard when it comes to diagnosing PCL and associated injuries[11]

- Acute: Determine grade of injury, as well as evaluating other potentially injured structures (e.g. ligaments, meniscus and/or cartilage structures of the knee). An increased signal or disrupted continuity of the ligament is expected[11].

- Chronic: MRI may appear normal in grade I and II injures.

- Bone scans: Best in chronic cases with recurrent pain, swelling and instability.

- Detect early arthritic changes before MRI or X-ray. These patients have a higher risk of developing articular cartilage degenerative changes, shown by areas of increased radiotracer uptake, most commonly in the medial and patellofemoral compartments.

- Ultrasound: More cost effective than MRI for evaluation

- Arteriogram: Evaluate the vascular status in the limb

Outcome measures[19][edit | edit source]

- Noyes knee score Questionnaire

- Lysholm score

- International knee dislocation score

- Multiligament Quality of Life questionnaire

- International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form

Medical management[edit | edit source]

Conservative management[edit | edit source]

Non-operative treatment of isolated PCL injuries has been shown to result in good subjective outcomes, as well as high rates of return to sport.[29] This approach is normally used for an acute, isolated grade I or II PCL sprains, if they fit the following criteria:[6][14][19]

- Posterior drawer <10 mm

- Decrease in posterior drawer excursion with internal rotation on the femur

- <5° abnormal rotary laxity and/or no significant increased valgus-varus laxity

Grade I and II PCL tears usually recover rapidly and most patients are satisfied with the outcome. Athletes are normally ready for return to play within 2-4 weeks.[15][19] Management includes:[6][19][20]

- Immobilise the knee in a range of motion brace locked in extension for 2-3 weeks

- Assisted weight-bearing (partial to full) for 2 weeks

- Physiotherapy

An acute grade III injury can also be managed conservatively. Immobilisation in a range of motion brace in full extension is recommended for two to four weeks, due to the high probability of injuries to other posterolateral structures. The posterior tibial sublaxation caused by the hamstring is minimised in extension, causing less force to the damaged PCL and posterolateral structures.[15][19] This allows the soft tissue structures to heal. Physiotherapy is recommended as part of the conservative management.[6] Return to play after conservative management of grade III tears is normally between 3 and 4 months.[15][19]

Chronic isolated grade I & II PCL injuries are usually managed conservatively with physiotherapy. Activity modification is recommended in chronic cases with recurrent pain and swelling.[6]

Surgical management[edit | edit source]

The primary objective during a PCL reconstruction is to restore normal knee mechanics and dynamic knee stability, thus correcting posterior tibial laxity.[15][19] There are different options of the optimal surgical approach for a PCL reconstruction. Debate exists about the best graft type or source, placement of the tibia, femoral tunnels, number of graft bundles and the amount of tension on the bundles.[15]

When using a double bundle graft, both bundles of the PCL can be reconstructed. A single bundle graft reconstructs only the stronger anterolateral bundle. The double bundle approach can restore normal knee kinematics with a full range of motion, while the single bundle only restores the 0°-60° knee range.[19]

Types of grafts include:[15]

- Allograft (mostly Achilles Tendon): Decreased surgical time and the absence of iatrogenic trauma to the harvest site. The Achilles tendon graft produces a large amount of collagen and ensures a complete filling of the tunnels. This is normally used to reconstruct the AL bundle. The AL graft is tensioned and fixed at 90° knee flexion.[19]

- Autologous tissue:

- Bone-patellar tendon-bone: Most common, as the bone plugs allow sufficient fixation of the tissue. The disadvantages of this graft are the harvest site morbidity and as a result of the rectangular form of the graft, the tunnels can not be completely filled with collagen.

- Quadrupled hamstring: Decreases the morbidity factor, but results in an inferior fixation method. A double semitendinosus tendon autograft is normally used for the PM bundle reconstruction. The PM graft is tensioned and fixed at 30° knee flexion.

- Quadriceps tendon: Has morbidity factor and adequate biomechanical properties.

Acute PCL injury[edit | edit source]

Surgical reconstruction of the PCL is recommended in acute injuries with severe posterior tibia subluxation and instability, if the posterior translation is greater than 10mm or if there are multiple ligamentous injuries. PCL avulsion fracture injuries fractures heal well when operated early on.[15][19] High demand individuals, such as young athletes, are normally treated with surgery as soon as possible, to enhance the chances to return to full functional capacity.[20] Grade III injury of the PCL are mostly combined with other injuries, and thus surgical reconstruction of the ligaments will have to be done, often within 2 weeks from the injury. This time frame gives the best anatomical ligament repair of the PCL and less capsular scarring.

Chronic PCL injury[edit | edit source]

Surgical intervention are recommended in chronic cases, considering the following (mostly in grade III injuries):[6][19]

- Recurrent pain and swelling

- Positive bone scan with the patient being unable to modify his/her activities

- In cases where combination injuries are present, surgery is indispensable

Surgical procedure[edit | edit source]

- Tibial inlay procedure: Starts with a diagnostic arthroscopy, but the inlay itself is an open surgery. The femoral tunnels are established with an outside-in technique to closely duplicate the femoral insertion of the PCL-meniscofemoral ligament complex. The graft is prepared during the exposure. Then it is placed in the graft passer and passed through the femoral tunnel, tensioned and screwed to the bone.

- Limiting knee range of motion bracing is needed after the surgery (see physiotherapy management).

- Tibial tunnel method: Arthroscopical approach. A guide pin is drilled from a point just distal and medial to the tibial tubercle and aimed at the distal and lateral aspect of the PCL footprint. The femoral tunnel should be placed just under the subchondral bone, to reduce the risk of osteonecrosis. The direction of the graft passage depends on the type of graft used. The tibial inlay procedure avoids this difficult part. The graft is placed in 70° to 90° flexion. In the single bundle reconstruction only 1 tunnel is drilled. In a double-bundle reconstruction two tunnels are drilled, which is technically more challenging.[15][19]

Complications[edit | edit source]

Possible complications after or during a PCL reconstruction include:[15]

- Fractures

- Popliteal artery injury

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Residual laxity (can be caused by an undiagnosed non-isolated PCL injury)

- Decrease range of motion (can be caused by improper placement or too much tension of the graft).

- Manipulation under anaesthesia can be considered to improve range of motion if physiotherapy is unsuccessful

Medical Management Biomechanics[edit | edit source]

Bundle Reconstruction or Conservative Management[edit | edit source]

The Posterior Cruciate Ligament’s primary function in the knee is to prevent posterior translation of the tibia on the femur. It consists of 2 main bundles: the anterolateral bundle (ALB) and posteromedial bundle (PMB). These parts work together to provide full protection in all degrees of flexion and pivoting. The ALB prevents external rotation, and the PMB prevents internal rotation. Together, they prevent anteroposterior translation through a codominant relationship. Their mediolateral components are valuable in protecting the knee from rotational forces in different degrees of flexion. The ALB is taut in flexion, and the PMB is taut in extension [30][31][32]. Although the tension differs at different degrees of flexion, their codominant relationship is put into effect based on their spatial orientation. With increased flexion, the ALB it taut and more vertically aligned. Due to this orientation, it is less able to resist posterior translation. However, the greater the flexion of the knee, the more horizontally oriented the PMB becomes, thus increasing its ability to resist posterior translation[33].

A tear or stretch will occur when the external force exceeds the capabilities of these tendons. The most common mechanism of injury is in a motor vehicle accident called the “dashboard injury”, where the tibia is forced into posterior translation on the femur. This often results in a multi-ligament injury and commonly require surgical intervention [32], but there are instances of acute injury as well. Low grade acute injuries are dealt with conservative treatment.

Conservative Treatment[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatment has been a common choice for PCL tear rehabilitation especially in grade I and II acute tears due to the ligaments strong intrinsic ability to heal [34][35][36]. During conservative treatment, the general rehab program would focus on building weight bearing capabilities and quadriceps strengthening[35]. The initial stage of healing focuses on maintaining range of motion and decreasing swelling and edema while protecting the PCL. To protect the PCL in later stages of healing, quadricep training begins, and hamstring exercises are avoided. The function of the quadriceps is to extend the knee, and due to its attachment site on the anterior side of the base of the tibial plateau; its accessory motion pulls the tibia forward on the femur when extending the knee pulling in the opposite direction of the PCL’s function. In contrast, Hamstrings are responsible for flexion of the knee, and would increase posterior sheer force from the tibia thus stressing or re-tearing a healing PCL. Walking is often included early in the rehab stages with a dynamic brace that allows for knee flexion but supports the tibia posteriorly.

The conservative treatments also apply to the post-operative protocol in patients for reconstruction, but they are usually shorter in duration[35].

Some studies have found negative long-term effects in the PCL with conservative treatment such as a higher degree of laxity and more incidences of degenerative changes in medial and patellofemoral compartments. Increased laxity means that the PCL is not taut in places where it should be, and the femur will translate farther especially in the posterior direction. The imbalance impacts the articular cartilage, and there is an increased amount of shear and compression forces on the tibial plateau. Over time, the articular cartilage degenerates, leading to an increased incidence of osteoarthritis and meniscal tears. Structures in the posterolateral corner are also at an increased risk of injury with a deficient PCL. The laxity changes the kinematics and loads on the knee during functional activities. In one study, a single legged lunge was performed with fluoroscopy in a person with a lax PCL and a person with an intact PCL. The results showed an increase in cartilage deformation on the tibia in the PCL-deficient knee[33] indicating a change in tibiofemoral mechanics as well.

Single Bundle Reconstruction[edit | edit source]

When the tear is Grade II or higher it may require reconstruction surgery. The Single Bundle Reconstruction (SBR) recreates the largest and stronger bundle of the two – The ALB. The ALB is the stronger bundle and is the primary restraint to posterior translation. The ultimate load failure of the ALB is nearly double that of the PMB: 1120± 362 N and 419±128 N respectively[37]. For the most people, this treatment has been good enough and allows them to continue their activities as before. However, without the two bundles, they do not have as much support in full flexion when compared to a double bundle reconstruction. SBR provides full anteroposterior support from 0-60° of flexion[38]. Most people do not require that much flexion in everyday activities.

SBR has some issues in the long term; many follow up studies show persistent posterior laxity of the knee and increased patellar femoral pressure[39]. This laxity means that the femur will move less predictably along the tibial plateau, increasing the risk of osteoarthritis and posterolateral corner injuries due to increased pressure[37].

Double Bundle Reconstruction[edit | edit source]

Double Bundle Reconstruction (DBR) is a relatively new method, and it attempts to better recreate the native PCL with the ALB and PMB. There is evidence that this method better recreates their codominant relationship thus restores the knee to greater stability for resisting posterior tibial translation than SBR[37][40][41]. Some studies show that it has less posterior laxity when compared to SBR and conservative treatment because of the codominant relationship[37]. In a randomized control trial comparing allografts of SBR and DBR, they found that DBR had better result in terms of laxity than the SBR. This was tested with subjective tests (International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC)), Subjective Knee Form, Lysholm Score, Tegner Activity Scale) and objective tests (reduced knee laxity)[42].

DBR was also better than SBR when comparing their posterior tibial translation. Tested under 134N of posterior tibial load at 30°, 45°, 60°, 75°, 90°, 105°, and 120° of flexion, DBR had significantly less posterior tibial translation than SBR. The most significant difference was at 105° of flexion, where the SBR knee had 5.3 mm more translation than the DBR. When compared to an intact knee from 0° to 15° of flexion, DBR had more posterior tibial translation [40]. This shows that the DBR method does not fully recreate the kinematics of a native knee. In addition, The DBR was superior when comparing to the SBR regarding rotational resistance[33][40].

Clinical and patient reported outcomes have not had any significant differences between DBR and SBR[37][41]. However, most patient outcomes are only comparing their post-op to their injured status, not their pre-injury status. This would be an area to focus further research on.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

The DBR provides more biomechanical support which leads to fewer negative outcomes in the long term than SBR or the conservative treatment. DBRs are usually considered for high performance athletes because they may need the stability in all degrees of flexion. However, based on findings in biomechanical studies, DBR should be considered as a treatment method for an average person. There are some reasons why DBR may not be considered, for example, if bone density is too low then it might not be safe to create the tunnels in the tibia for the graft’s attachments. People with low bone density or osteoporosis would be safer with SBR or conservative treatment, as fewer tunnels reduce fracture risk in this group.

It is important to know that neither method, SBR or DBR fully recreated native knee kinematics, and there is no current agreement on which method is better. The disagreement arises from the variability in other aspects of a PCL reconstruction such as graft type, graft tension, angle of implementation, graft tensioning, and surgical technique (tibial inlay and trans-tibial). Future studies should compare knees under similar conditions with larger sample sizes for the best results. However, it would still be difficult to understand the clinical outcomes because it is difficult to compare to a pre-injury or pre-laxity status.

Conservative treatment methods are also very effective in post-op to decrease future risk of injury and to reduce residual laxity long-term. Knee immobilization for 3 days before moving to a dynamic knee brace and progressive weight bearing, avoiding hyperextension, and strengthening the quadriceps are the common post-op methods[36]. and recommended for quick recovery

Physiotherapy management[edit | edit source]

Conservative management[edit | edit source]

Grade 1 & II injuries[edit | edit source]

Two weeks of relative immobilisation of the knee (in a locked range of motion brace) is recommended by orthopaedic surgeons. Physiotherapy in this time period includes:[6][13][15][19]

- Partial to full weight-bearing mobilisation

- Reduce pain and inflammation

- Reducing knee joint effusion

- Restore knee range of motion

- Knee strengthening (especially protective quadriceps rehabilitation)

- Strengthening the quadriceps is a key factor in a successful recovery, as the quadriceps can take the place of the PCL to a certain extent to prevent the femur from moving too far forward over the tibia.

- Hamstring strengthening can be included

- Important to incorporate eccentric strengthening of the lower limb muscles

- Closed chain exercises

- Activity modification until pain and swelling subsides

After 2 weeks (on the orthopaedic surgeon's recommendation):[13]

- Progress to full weight-bearing mobilisation

- Weaning of range of motion brace

- Proprioception, balance and coordination

- Agility programme when strength and endurance has been regained and the neuromuscular control increased

- Return to play between 2 and 4 weeks of injury

Grade III injuries[edit | edit source]

The knee is immobilised in range of motion brace, locked in extension, for 2-4 weeks. Physiotherapy management in this time includes:

- Activity modification

- Quadriceps rehabilitation

- Initially isometric quadriceps exercises and straight-leg raises (SLR)

- Avoid isolated hamstring strengthening

- Active-assisted knee flexion <70°

- Progress weight-bearing within pain limits

- Quadriceps rehabilitation: Promote dynamic stabilisation and counteract posterior tibial subluxation

- Closed chain exercises

- Open kinetic chain eccentric exercises and eventually

- Progress to functional exercises such as stationary cycling, leg press, elliptical exercises and stair climbing

Return to play is sport specific, and only after 3 months.[13]

Chronic injuries[edit | edit source]

Chronic PCL injuries can be adequately treated with physiotherapy. A range of motion brace is used, initially set to prevent the terminal 15° of extension. After a while the brace is opened to full extension.[19]

Post-operative rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Post-operative rehabilitation typically lasts 6 to 9 months. The duration of each of the five phases and the total duration of the rehabilitation depends on the age and physical level of the patient, as well as the success of the operation. Also see page on PCL reconstruction.